Our Tax System’s Unproductive Love Affair with Capital Gains

The other day, I saw this chart floating around Twitter:

This was rage-bait, and baby, I was hooked, lined, and sunk.

It was accompanied by the claim that Jeff Bezos paid a 23% effective tax rate* on $4 billion in reported income between 2014 and 2018.

Having just forked over multiple six figures in taxes for 2023, I was curious what our effective tax rate was—so I sat down and calculated it. We paid 26%. You see, as far as the US tax code is concerned, we made one major, rookie mistake: We worked for money.

As the chart above shows**, the top marginal tax rate has been falling for decades. It peaked in the 1940s at 94%, dropped to the 70% range in the 1960s, and stayed there until the 1980s when it dropped from 50% to the high thirties. It’s bobbled in the mid-30% range ever since, clocking in at 37% today for incomes above $609,351 for singles and $731,201 for couples.

The primary argument for lower top marginal tax rates is relatively simple: If you tax income too much, you disincentivize people from working, and that portends No Good, Very Bad Things for the economy and society at large. For example, today, you cross over from the 22% bracket to the 24% bracket around $100,000 in income as a single person.

“What if you only kept 5 cents of your $100,001st dollar earned, and had to wire the rest to the Feds?”

But what if you crossed from 22% to 95%? What if you only kept 5 cents of your $100,001st dollar earned, and had to wire the rest to the Feds?

If given the opportunity to work 30 hours per week for $100,000 or 60 hours per week for $200,000 in this tax regime, the choice to continue working only 30 hours per week would be pretty easy since a 100% increase in your output would earn you just 5% more.

Paradoxically, this means extreme tax rates can actually lower tax revenues, because people will work (and earn) less, and therefore have less income to pay taxes on. (This is how we ended up with the 1980s-era magical thinking that the best way to increase tax revenue is to keep cutting taxes. You can see how this idea breaks at extremes.)

Taxation acts as an incentive—or disincentive—for productive capacity. Assuming people are behaving rationally, some tax choices boost economic output and others undermine it.

Through that lens, why are capital gains taxed at a much lower rate than wages earned from productive labor?

Imagine you have two people: One was given $10,000 when they graduated from college in 2005 and invested it in a hot stock called “Amazon.”

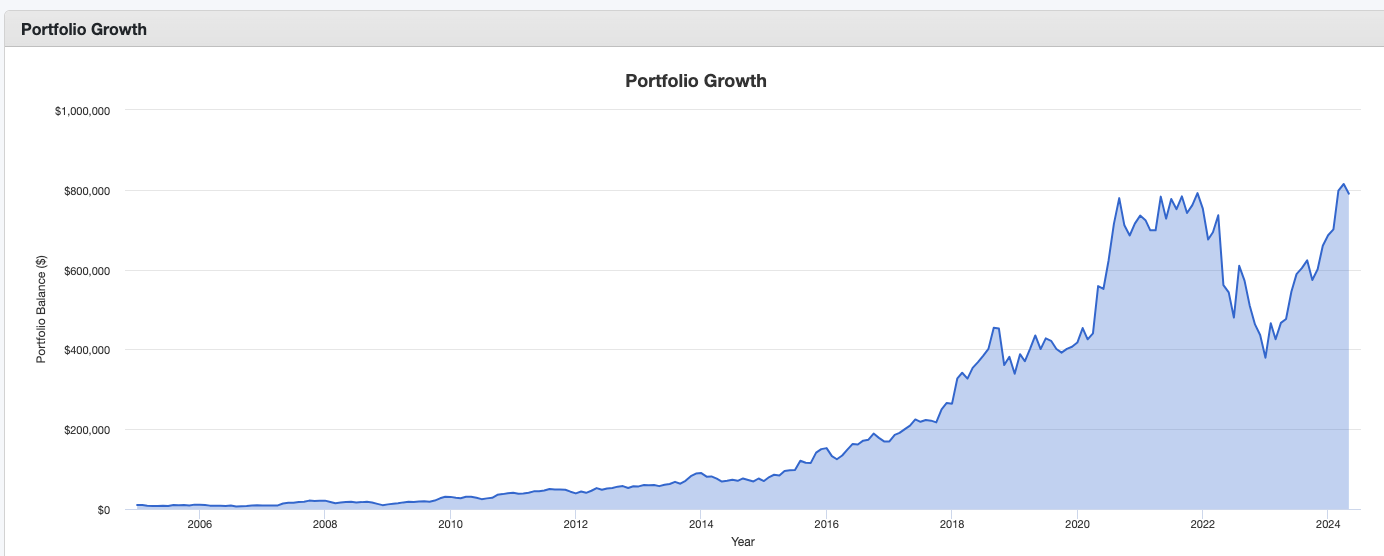

You know what happens next:

Having held for 20 years, today they’d have roughly $780,000 in capital gains on their $10,000 AMZN stock purchase. They decide to take the year off, and live high on the hog using investment income. They withdraw $250,000 and perform no labor.

The second person works for Amazon—maybe they’re an executive or a mid-level manager, and they’re paid a juicy salary for their labor of $250,000.

Both people have $250,000 in income. One contributed zero hours of labor to the economy. The other contributed around 1,800 hours.

The person who contributed nothing in economic value will pay a top marginal tax rate of 15% and end up with a total tax bill of $30,629, while the person who worked for 1,800 hours will pay double on the same income, at a top marginal tax rate of 32% (after the standard deduction) and a total tax bill of $54,997.***

Symbolically, our sweet little AMZN shareholder’s gap year is being subsidized by the Amazon executive, who’s not only paying a marginal tax rate that’s twice as high, but also contributing 2,000 hours of economic output to the company.

Assuming I’m a rational actress in this system who wants to take the path of least resistance, what am I more incentivized to do, labor for income, or derive income from capital?

“Assuming I’m a rational actress in this system who wants to take the path of least resistance, what am I more incentivized to do, labor for income, or derive income from capital?”

So I, ever a rational actress at age 24 studying the tax code for the first time, looked at my options and thought, “In this job market with an ever-declining labor share of income, working earns me $60,000 taxed at a top marginal rate of 22%…or, I can work several jobs simultaneously for a decade, save aggressively, amass $1.5 million in investments, quit work at 35, contribute no productive economic output anymore, live on $60,000 in investment income every year taxed at 0%, and neither work nor pay taxes ever again.”

(Really, the internal dialogue went something like this: Mama no likey cubicle; dónde está Vanguard account?)

As an individual investor, this system rules! It is easily hacked. The loopholes are obvious. (The entire FI/RE movement is emblematic of said loophole.)

But as an incentive structure for growing the real productive output of an economy? It’s questionable.

This core question is: What do we want to incentivize, labor or investment? And if your answer is “both,” why not tax them the same way? (Technically, the thing our tax code incentivizes most is neither work nor investment, but inheritance—a person who has never worked a day in her life can take home north of $13 million in inheritance income before paying a dime in taxes.)

The brilliant Michael Green, portfolio manager and chief strategist at Simplify, commented on this inheritance dynamic in an interview, but I think his sentiments are valuable in the capital gains discussion, too: “Why are we encouraging that as a society? We’re not capital short. If anything, we’re income short. [I would] encourage you to recognize that…everything we’ve all built together is increasingly at risk of being torn down because we’re fraying in our society. So you can choose to optimize your own personal outcome, but man, your grandchildren are going to be living in a much worse world because of the choices that you’re making today.”

This debate is playing out in the news cycle right now over a new proposal that would increase the top marginal capital gains tax rate to 39.6% for households that realize more than $1 million in capital gains per year.

In other words, it proposes taxing the 0.4% of Americans who earn more than seven figures in investment income the same way a high earner who’s working for that income would be taxed. (Critics point out that such a change would disproportionately hurt Baby Boomers aging out of small business ownership and selling their firms for millions of dollars.)

“I find it hard to believe that keeping taxes lower for the shareholder than the worker is what will create real economic growth.”

Another popular complaint about taxing capital gains like they’re income from labor is that it’s “double taxation.” But that’s technically an economic fallacy: Much like the flow of new income you derive from your human capital is not “double” taxed, neither is the flow of new income you derive from financial capital. The original financial capital was taxed, sure, but capital gains are new income.

Others opine that increasing top marginal capital gains tax rates will lead to people realizing fewer gains, and therefore decrease tax revenue, rather than increase it. They cite the economic reasoning of the late 1970s, that low capital gains taxes “stimulate job creation and economic growth” (also known as: trickle-down economics).

As an investor who hopes to have millions in capital gains someday, my confirmation bias would love to embrace that reasoning.

But as a citizen of a country that’s forty years into an economic experiment in which most of the gains are decidedly not trickling down, I find it hard to believe that keeping taxes lower for the shareholder than the worker is what will create real economic growth.

—

*This data was accessed via an ex-IRS contractor named Charles Littlejohn, who leaked the tax returns of the rich to show the public how the uber-wealthy game our tax code. He was sentenced to five years in prison in January 2024.

**Technically, the chart shows a falling effective tax rate, but the cause of a falling effective tax rate is lower marginal tax rates.

***I like to use TaxAct’s calculator to quickly play around with these hypotheticals.