Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

I typically follow a simple social media strategy: Get incensed or enthused about a topic, then make a quippy, shareable, and, crucially, under-90-second breakdown. The simpler and timelier, the better.

So when I shared a meandering, four-minute-long diatribe titled “healthcare hellscape vlog” in which I took the viewer on a spliced-together journey of my (failed) attempt at negotiating the cost of a $564 post-insurance medical bill for an office visit, I had already accepted my algorithmic fate: Zuck was going to punish me for this.

>

“Finally, one commenter snapped us out of it: ‘We shouldn’t have to do this for something we pay thousands of dollars a year for.’”

Dear reader, this was a seismic miscalculation. It turns out Americans hate insurance companies more than Zuck hates our attention spans. Instagram’s built-in insights told me the video was shared nearly 3,000 times in a few days. It accumulated 798 comments of commiseration, frustration, and confusion. That type of engagement is usually reserved for Ballerina Farm or political controversy.

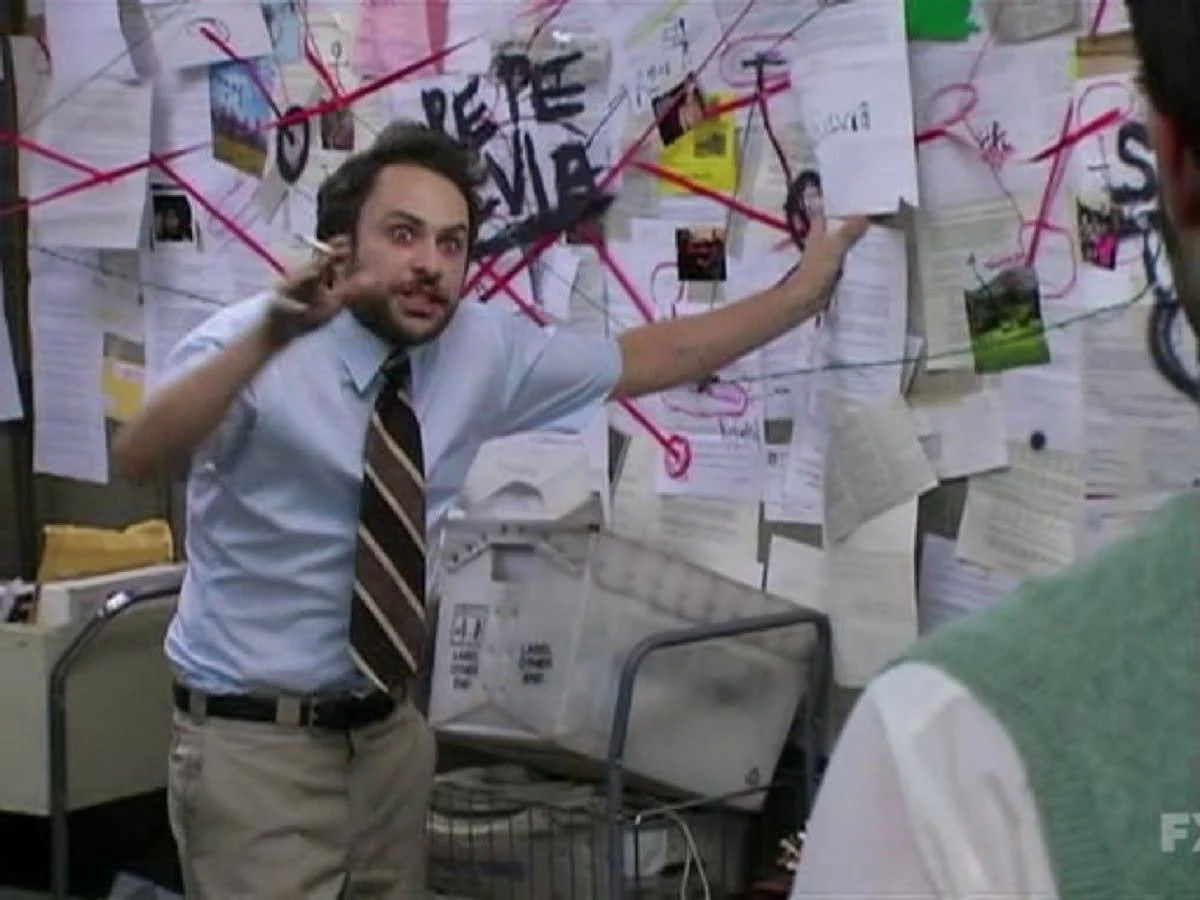

We crowdsourced creative approaches in the comments. Billing department employees, physicians, and chronically ill folks alike chimed in with their favorite workarounds for navigating this dystopian labyrinth; call the medical provider first and ask for the cash-pay rate without divulging you have insurance; no, call the insurance company first and request an estimate; no, that won’t work, because they’ll tell you they don’t know; no, you need to find the secret Excel file with the procedure codes; no, not THAT Excel file; no, let the bills go to collections and then commence mob-boss-style hardball negotiations.

The comments section felt like a collective effervescence, and also, this meme:

Finally, one commenter snapped us out of it: “We shouldn’t have to do this for something we pay thousands of dollars a year for.”

Historically, the FI/RE (financially independent, retire early) community hasn’t had much to offer in the way of advice for these concerns in the US. More often, questions about how to fund healthcare in early retirement are met with shrugs of resignation at best, and naïve, eugenics-y health platitudes at worst (“Just eat right and exercise and you’ll never have to worry about healthcare expenses!”).

I know this because I used to respond this way (with the shrug, not the eugenics). When people would reach out and ask the eminently reasonable question of how to account for $1,000 monthly premiums and $15,000 out-of-pocket maximums in their financial independence number after untethering from corporate benevolence, I’d find rambling ways to conceal the fact that I had no idea. The solution was always the same: Just save more money. Pete Adeney, the prolific Mr. Money Mustache, has famously opted out and doesn’t have insurance at all, opting instead for a direct primary care model.

In the best cases, you’ll find advice for how to negotiate medical bills (to varying degrees of success), but funding your own insurance in a system designed to sop up as much liquidity as possible from whatever’s sloshing around in S&P 500 benefits reserves is astronomical even for the worst plans, and they’re only getting worse.

>

“There are no good answers for individuals, because this is a universal problem in need of universal overhauling.”

There are no good answers for individuals, because this is a universal problem in need of universal overhauling. The only real solution is to burn the whole thing down and start over. The sooner we can collectively get onboard with this reality, the better for everyone. We could start by dropping the phrase “socialized medicine,” propaganda that prominent ex-insurance executive Wendell Potter admits was dreamed up in a Cigna boardroom. (There is an embarrassing amount of evidence that a single-payer system would be $450 billion cheaper each year. A society that believes a small number of people should be permitted to get rich off the financing of medical expenses has lost its way.)

In the absence of systemwide changes to the rules (and the banding together that would require), people are left to individually perfect their level of game play. Much like the FI/RE community jumps through loopholes to navigate this playing field, similar attitudes are present in another community preoccupied with winning the game of life: the biohackers. In both, a deep but scarcely acknowledged sense of structural precarity fuels an obsession with extreme optimization. Derek Thompson recently pointed out a crucial aspect of this pursuit of efficiency:

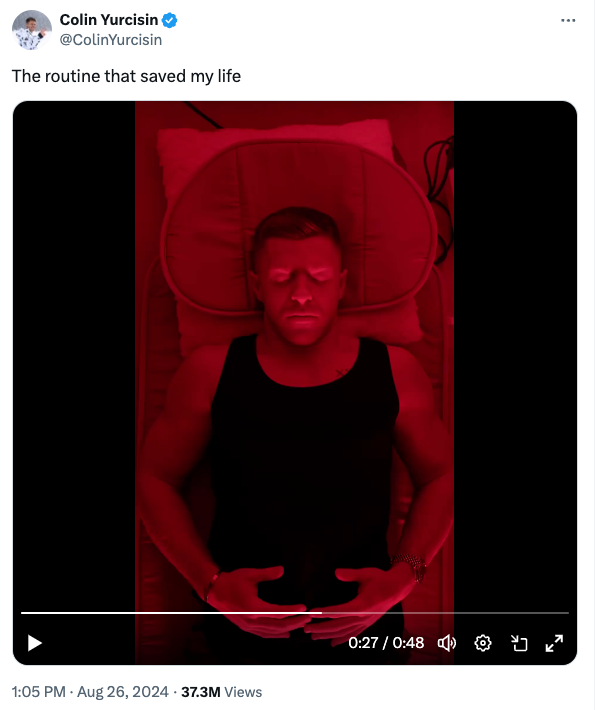

To save you the 47 seconds of what I can only describe as “American Psycho produced by Andrew Huberman,” a beefy, chronically shirtless man awakens sitting upright, gazes into his own eyes as he removes his mouth tape, brushes his teeth, puts on a sassy little outfit, pulls his Rolex out of a grayscale Louis Vuitton box, drinks espresso, lights a candle, journals, takes supplements, enters a red light chamber, meditates in a different red light chamber, starts his Lamborghini, of which we get eight (8) gratuitous angles, goes to the gym, works out (shirtless again), cold plunges, swims, and then reads a book (my money’s on Atomic Habits or something by Mark Manson) in a sauna in his backyard. This is, allegedly, the “routine that saved his life.”

I’m two years alcohol-free, but the vacant precision of the self-improvement in this video makes me want to go on a bender fueled by intravenous espresso martinis just to restore balance in the universe.

>

“Optimization is a response to things getting worse. We don’t usually experience the impulse to optimize when we feel we have plenty.”

Obviously, nobody in their right mind is actually living this way (and I can begrudgingly admit to enjoying a cold plunge), but it’s telling that this brand of lifestyle content codes as aspirational to a significant subset of young people. And Derek’s observation—that this hyper-optimized brand of self-obsession all but requires the metaphoric or literal absence of the needs of other people—is a critical component. This is a worldview that teaches happiness is found via meticulous construction of a life you can frictionlessly glide through, all your rough edges sanded down. It’s a life in which you are accountable to nobody but your two-hour morning routine and arduous “self work,” the more burdensome and relentless, the better.

The idea that we all must be constantly “working on ourselves” is the undergirding assumption of so much of modern life, personal finance included, and it’s a covertly appealing one: It prescribes giving a shit about nobody but yourself. But optimization is a response to things getting worse. We don’t usually experience the impulse to optimize when we feel we have plenty. If you’re guaranteed a month of paid vacation each year like the French, you probably aren’t stressing about how you’ll spend each and every hour of your down time.

Optimization is often a reaction to a life that’s both too full and too empty, and the subconscious awareness of a seemingly bottomless pit of risk. There’s a reason the people who live in the countries with social safety nets are chain-smoking Camels and drinking espresso at 4 pm to gear up for a cheese plate tour of the town square instead of “biohacking.” When you feel like the rug could be pulled out from under you at any moment, there is no room for error. This is a feature, not a bug, of the American status quo, which is most adept at creating problems for which it can sell you solutions.

The other day, a friend who outside of Portland texted me to express concern about the people who go to her gym, whom she described as “the raw meat types.” “They all walk around barefoot,” she whispered to me in a voice note from the parking lot, “so I’ve been spreading light paranoia about athlete’s foot.”

Apparently, four of the four people with whom she raised the issue assured her that if you “just don’t think about it,” you’ll be fine. The mind has control over the body, they lectured her, so to remain healthy, she should think healthy thoughts. “I don’t think that’s how fungal infections work,” she said. She sounded disoriented.

This is the reassuring, mystical logic of self-optimization: That if I am healthy, natural, perfect, streamlined, I will not suffer. Transcend your own human form and all its pesky co-pays via Thinking Positive Thoughts and drinking raw milk. It is, at its core, a deep desperation for control; an every-woman-for-herself ethos that says there are “superior” people, and with enough obsession and focus, you, too, can become superior, and if you’re superior, who cares if our healthcare system is a too-big-to-fail, vibes-based cartel? The inferior people deserve their fate. (I promised you eugenics, and now I am delivering.)

The self is the final frontier of this optimization effort, which is how we ended up with influencers like this guy:

I know you’re not going to believe this, but if you’re ready to “acquire valuable datasets,” do “group workouts,” and “raise your collective consciousness,” you can join his Mastermind, Leveraged Lifestyle. This can all be yours for the low, low price of $1,997.

To a person who feels protracted overwhelm, this rugged individualism can feel like salvation (after all, it certainly narrows your focus via “the complete absence of other people”). But this prescription insulates you from the type of connection with others that would allow collective recognition to take place. Reducing your life to an enormous checklist of physiological maintenance implies that our shared symptoms can and should be managed with more concentrated individual effort. This fracturing distracts from the reality that everything from lax food regulation to ever-rising insurance premiums drives all of us further into our siloes of escalating self-work, saving, and stressing.

>

“The feeling that provides the thrust for this worldview is legitimate and deeply human. It’s the solution that ultimately proves hollow. ”

As a former group fitness instructor who bears an alarming and readily searchable internet record of enthusiastically endorsing “optimization” of all sorts, I am guiltier than your average person of investing too much faith in the promises of a #streamlined existence. It assures you deliverance from risk, suffering. Who doesn’t want that? The feeling that provides the thrust for this worldview—a desperation for control and a better life—is legitimate and deeply human. It’s the solution that ultimately proves hollow.

Resist the insistence that you are a commodity to be optimized. Luxuriate in your human inefficiency! Streamlining yourself into oblivion has the same resigned pitch as the healthcare advice to “save more money,” and it’s ultimately futile for the same reason: You will never arrive. The human cost will continue to rise for as long as it is permitted to do so.

September 3, 2024

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time