Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” —F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Rich Boy, 1926

“You know how people who come into money suddenly look better?” I texted my friend the other day as I breached the threshold of the grocery store’s automatic doors. “How does that happen? How do I hire someone to give me a glow-up?” The question had occurred to me on the silent car ride to the store after I caught an unflattering glimpse of myself in the rear-view mirror. I considered it further as I plucked a bunch of green onions from a wall of vegetables and plunged a damp handful into a produce bag. Her response blooped into our open chat, face up in the cart, almost immediately. “What do you mean?” Then another: “Do you have a certain celebrity in mind?”

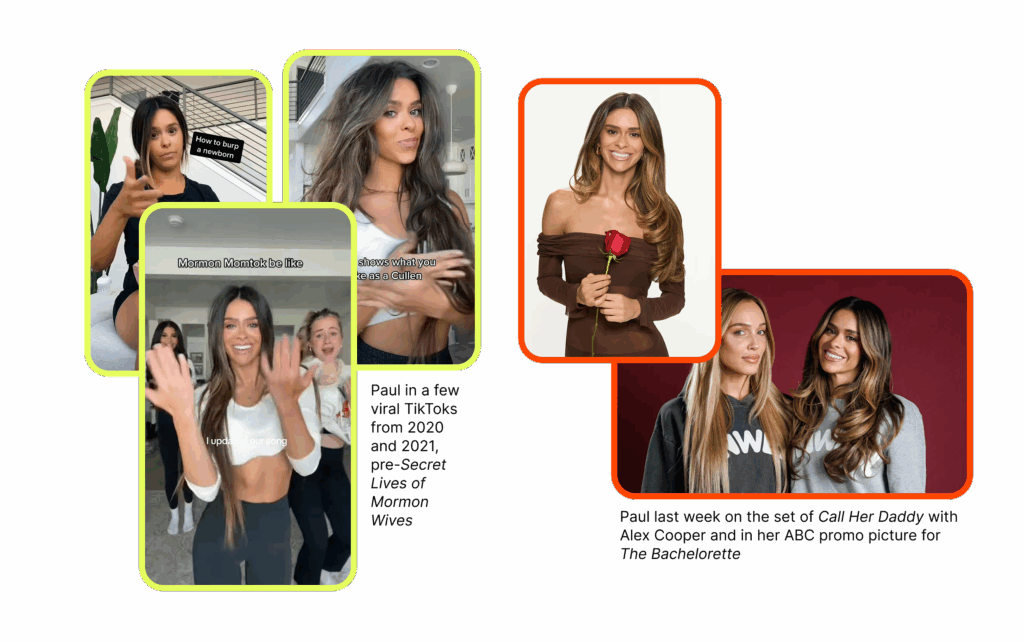

I scanned my mental Rolodex for an emblematic case study as I pushed my way down the cereal aisle, then pulled over next to the granola. “I guess Taylor Frankie Paul?” I responded. The triple name in question, a troll-y momfluencer who became popular on TikTok for the sort of provocative yet vanilla dance videos that launched the entertainment careers of many a white woman since 2020, perfectly embodied the subtle metamorphosis in question.

Paul was swept into mainstream fame last year thanks to the bewildering popularity of the Hulu reality series The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives. (I have, of course, seen every episode.) Her physical transformation since then has not been dramatic—to be a TikTok It Girl, your starting point must be conventionally attractive—but it is noticeable, especially if you’re attuned to the way wealth slowly, visibly announces itself. Paul is a fan-favorite “character” in the Mormon Wives universe because she’s the only cast member whose personality doesn’t seem buried beneath layers of posturing and self-conscious image curation. (The series opens with police body-cam footage of an intoxicated Paul being arrested for fighting with her boyfriend.) She’s a flawed person, and she knows it, which makes for excellent television. It was just announced that she’ll be ABC’s next Bachelorette, the first time the leading lady has been sourced from outside the franchise.

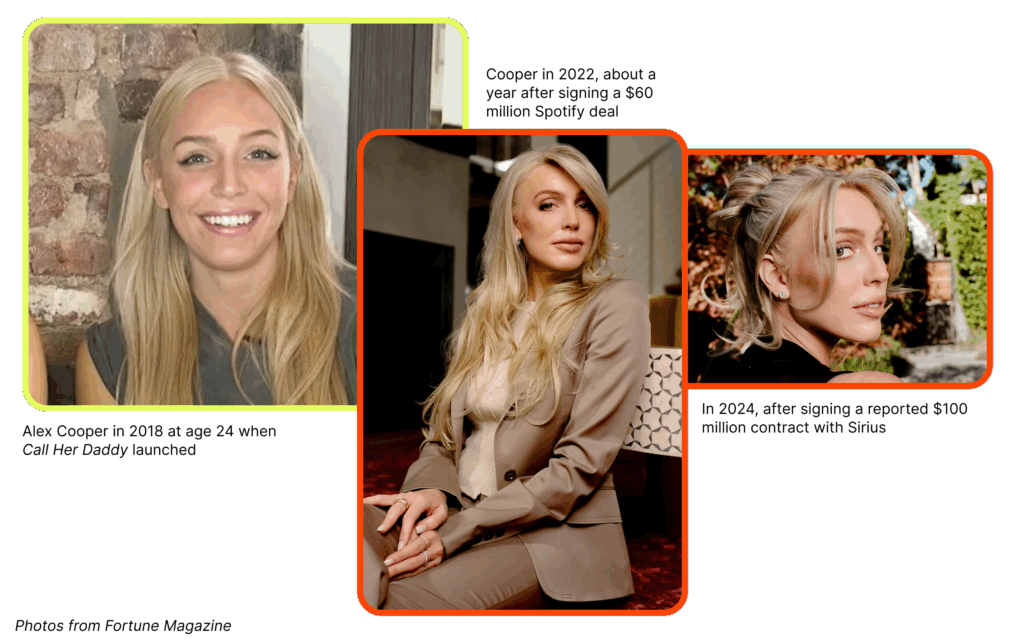

The glow-up pattern typically goes something like this: Normal traits like dull skin, a bad fake tan, blocky eyebrows, and often long, harshly highlighted hair—what I can only describe as the suburban mall aesthetic of my adolescence, like Victoria’s Secret PINK sweatpants tucked into worn, chocolate brown Uggs—are refined into a glossy, glowy, and windswept look that telegraphs access to a vast and accommodating glam squad. Paul appeared earlier this week on Alex Cooper’s Call Her Daddy to discuss her casting as the Bachelorette; Cooper herself might be an even more illustrative case of “Regular Midwest Suburban Hot Turned Upper-Class Hot” after she clinched a multiyear, $60 million podcasting deal with Spotify in 2021.

Most rich women in the public eye tend to adhere to this visual code: luscious, tastefully colored hair; a frozen forehead; eyes that, through cosmetic intervention or actual rest, always appear as though they’ve freshly awoken from a nap in a cryo chamber. (In last week’s newsletter, I included a subway ad for the editing app Facetune that instructed, menacingly, “Look like you had 8 hours of sleep.”) When taken to extremes, the look in question can appear surrealist—embalmed, even—but there’s a sweet spot before the fillers start to migrate that suggests life is as frictionless as one’s glassy skin. Despite my commitment to proselytizing the Gospel of the Hot Girl Hamster Wheel (that beauty labor is not only time- and money-intensive, but also a waste of both for most normal people), it was notable when these two women, almost exactly my age, gradually Animorphed on my screen as they became wealthier.

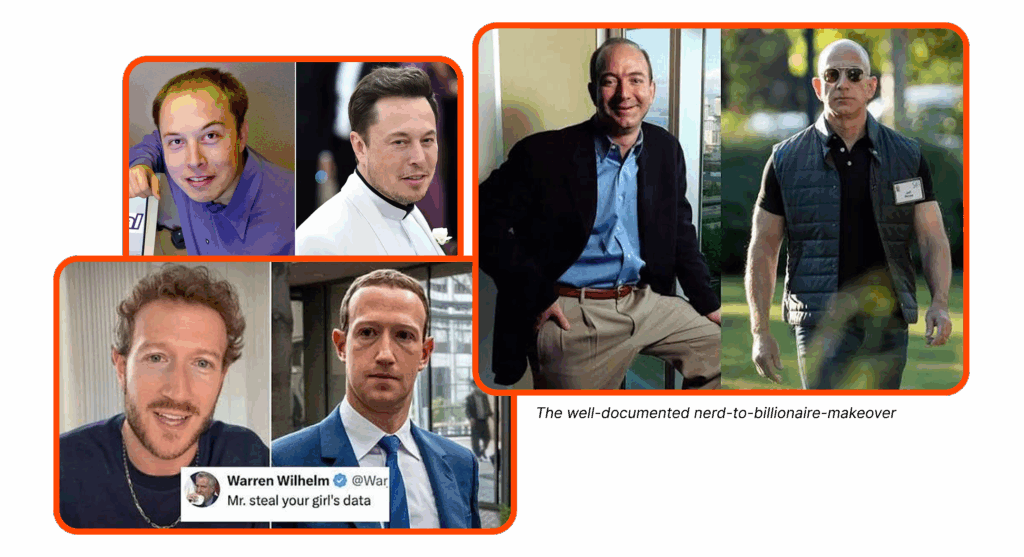

The Kardashians are towering totems on Glow-Up Easter Island, from which the “You’re not ugly, you’re just poor” meme originated. Even rich men reliably undergo a similar physical transformation, as many have noted about Jeff Bezos (Mr. Clean cosplay), Mark Zuckerberg (“hit with the Dominican ray”), and Elon Musk (hair plugs).

By the time I found myself wheeling down the dairy aisle, I was pretty sure there was an underground, invitation-only industry of LooksMaxxing professionals activated via Bat-Signal once one accumulates enough money and prominence to score their recognition. My friend had a different theory. “I think these people slowly accumulate teams,” she hypothesized, “but it probably starts with a stylist, who then recommends a colorist, who might offer an aesthetician referral, and so on.” This sounded more complicated and slipshod than my Centralized Cabal theory, but the slow burn is probably more realistic.

Still, the mechanics of this now-predictable transformation continue to interest me: How does this begin, technically speaking? Is the newly flush-with-cash person assigned a Glow-Up Director by the Deep State to execute tactics from a fine-tuned, well-coiffed playbook? Are they consciously seeking out this particular aesthetic, or is the process less intentional? Could you walk into a salon in West Hollywood and ask for the Recently Viral Special? And maybe most importantly, what does it mean that wealth tends to physically manifest in such a uniform way; that “1%” is a distinct and differentiating aesthetic category as much as it is an income bracket?

That rich people look different than the rest of us is mostly accepted wisdom at this point. (One Reddit thread I found theorized the simple fact of never worrying about rent would make somebody look less haggard.) Even those who are wealthy outside the public eye tend to dress and carry themselves differently, a fascination inflamed by HBO’s Succession, which created a cottage industry of fashion freelancers producing an endless barrage of “old” vs. “new” money style write-ups in 2023. The popularity of brands like Loro Piana and The Row, synonymous with an understated expression of asset accumulation, crescendoed.

As I shopped for the rest of my dinner, I continued to meditate on the shiny hair and glowing skin that wealth has unlocked for my contemporaries. Beauty has long been associated with goodness—and, as I wrote in Rich Girl Nation, capital. A straightforward example comes from the Tinder-simple moralizing in Disney movies: The evil witches are ugly; the pure princesses are beautiful. Despite my constant “class consciousness” rallying, the focus of my curiosity was not an academic inquiry into how such a transformation served to visually separate the rich from the hoi polloi or soften our perceptions of them, but where I could score some glow-up juice for myself. (I am but a simple, shallow observer who’s closer to her southern sorority girl roots than I like to let on most days.)

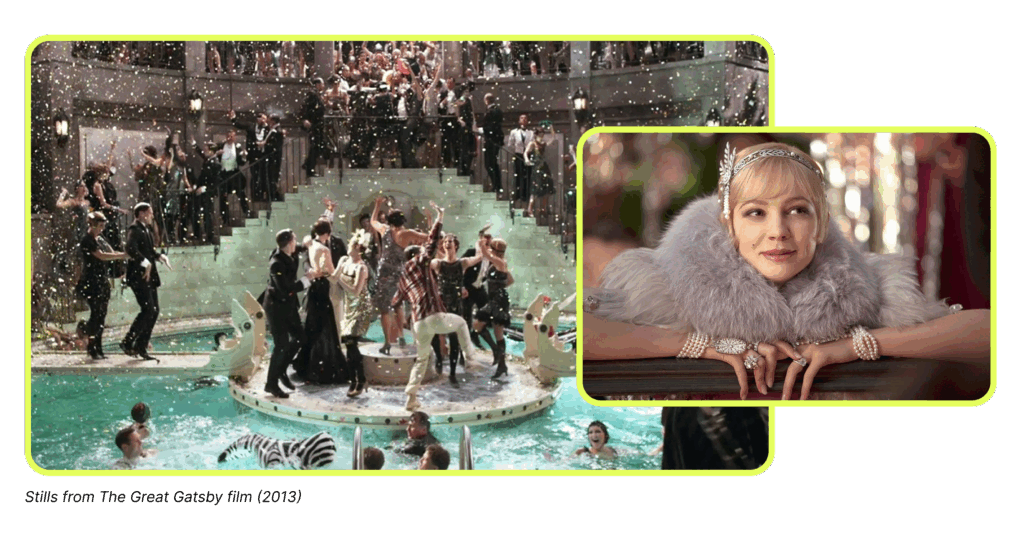

The finer points of the behavior, aesthetics, and proclivities of the rich have fascinated American writers for as long as the stratospheric class has existed. F. Scott Fitzgerald obsessed over the visual particulars of the wealthy in exquisite, literary detail at the height of their frivolity and excess during the 1920s. His scenes unfolded in the aftermath of the Great War (later rendered “the first” by its catastrophic sequel a couple decades later), a time which set the wheels of our favored American pastimes—economic dominance, consumerism, inequality—more decidedly into motion. Thanks to Prohibition, swaths of libertines were becoming wealthy, and quickly. Like the modern TikTok star-cum-celebrity, there was a grain of truth to the American dream of striking it rich.

Fitzgerald himself was, at least for a time, close to his subject. By 1925, when he published The Great Gatsby (the book celebrated its centennial in April), he reportedly earned an average of $24,000 per year, an income which catapulted him into the top 1 percent. (While the consumer price index was brand new then, having been developed in response to post-war inflation, one estimate said this would be equivalent to about $500,000 today—and with a far lower tax burden.) Back then, such an income could purchase a soccer team of servants. Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda had a “butler, chauffeur, yard man, cook, parlor maid and chamber maid,” plus “a laundress.” (The original glam squad?) He was infamously bad at managing money—at the time of his death in 1940, his estate was only worth around $35,000, or less than $1 million in today’s dollars.

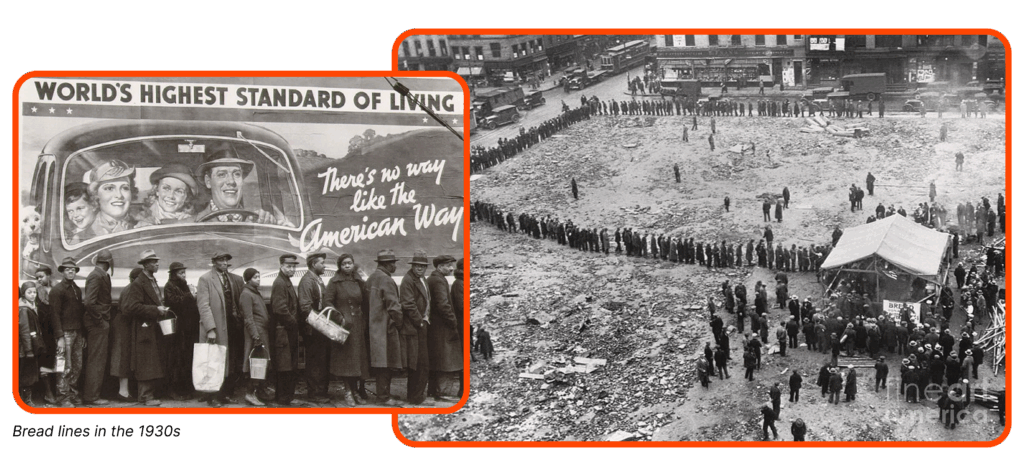

Gatsby, for all its superficial glitz and glamor, also captured the era’s underlying moral rot, and carried with it an ominous warning of impending doom. Of Fitzgerald’s mindset while writing Gatsby, one history buff observed that he seemed to “have already foreseen the lasting consequences of America’s heady romance with capitalism and materialism.” His warning went unheeded. Just four years after the book was published, the Great Depression began.

It’s hard not to feel as though we’re approaching a precipice of similar historic magnitude. The parallels are eerie and numerous, beginning with the 2020 global pandemic which mirrored the deadly 1918 global influenza, moving swiftly into the “Roaring Twenties”-style crypto bubble of the early 2020s. The racist moral panic du jour in the 1920s surrounded the influx of Italian immigrants, who were considered non-white and believed to have an ethnic predisposition to Doing Crimes. (Catholics were also viewed with suspicion and disdain, which means I would’ve been in double jeopardy.) In 1928, a year before the crash, the top 1% of households received 23.9% of all pretax income; the bottom 90% received 50.7%. As of 2022, we were approaching similarly barbaric levels of inequality: The top 1% received 20.7%; the bottom 90%, 53.2%. The polarization of the early twentieth century is typically characterized as “urban” vs. “rural”; today, that fight goes by a different name: “left” vs. “right.” Then, as now, the true distinction was capital vs. everyone else.

My politics are primarily concerned with economic justice, built on the foundation that people’s behavior and beliefs are inherently malleable and shaped to a large degree by their material circumstances—not unlike the bleached, mall-going Every Girl transformed by new media money into a millionaire with honeyed hair and tasteful cosmetic work, or the low-income worker turned virulent bigot in the face of decades of offshoring and wage stagnation. It’s easier to dismiss fanatical claims about the devious immigrants and trans people stealing your jobs and houses when you already have both jobs and houses. (This theory’s most obvious logical gaps are wealthy Baby Boomer conservatives, who own the majority of our country’s wealth and houses, and low-income progressives, who own virtually none of it.) The relationship between one’s circumstances and political beliefs is far from perfectly linear or rational, but one thing is for sure: The ultra-rich, unlike the rest of us, have outstanding class solidarity, which regularly transcends the left-right political spectrum altogether.

The 1920s-esque inequality we face now is anathema to social cohesion. It is a fundamentally unstable molecule posing a constant risk of nuclear meltdown, because humans are less homo economicus than homo socialis. Our interpretation of our socioeconomic standing is comparative and relative, not absolute. That’s why data purporting to show the median American is better off in real terms than they were 30 years ago is less supportive evidence of economic contentment than one might assume. What counts to homo socialis is how much further away the richest have floated on the upthrust of everyone else’s work.

There are academic explanations for why severe inequality is toxic to the body economic—inefficient concentration of power over labor, the law of diminishing marginal returns to consumption, increasingly speculative investment behavior, breakdown of basic public services—but that omits what is perhaps the most damaging element, which is the poison that oxidizes in one’s gut when watching another individual spend $50 million on a Venetian wedding while workers in his warehouses file lawsuits over human rights abuses. That, it goes without saying, should be viscerally offensive to the basic morality of any person whose operating system has not been irredeemably corrupted by a steady stream of Grant Cardone videos. What would Fitzgerald have to say about how reality TV, billionaires, and President Reality TV Billionaire have accelerated this social breakdown?

Historically, nations in a position this precarious swing right, and swing hard. Italians and Germans embraced fascism in the 1920s and 1930s after the war left them in various states of economic instability, social fragmentation, and wealth inequality, their disillusioned citizens grasping at nationalism for answers. But the US, protected by its geographic isolation and a lack of humiliating post-war reparations, avoided this fate, responding to its own crisis by shifting leftward. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal invested heavily in prosocial programs like Social Security, reformed the financial sector, and established labor rights with the Wagner Act.

This isn’t because Americans were immune from flirting with fascism, but because American institutions responded differently. They (accurately) assigned blame for the country’s economic troubles to banks, monopolies, and wealth concentration, where charismatic leaders in Italy and Germany blamed Jews, Communists, and other minorities. In each case, solutions were devised according to these narratives about who bore responsibility. Where others crumbled under the toxic weight of hypernationalism, state repression, and militarization, the US embraced a racially stratified spate of social programs and public works. (It’s important not to overstate things: FDR’s democratic populism was still designed to rescue and preserve the basic structure of capitalism, making it, one could argue, an inherently conservative project.) Still, the last time a proto-class consciousness meaningfully took hold in the US, the country navigated away from a profound crisis that could’ve otherwise taken a much more violent and destructive turn.

Fitzgerald published his cautionary tale on the eve of a national collapse. We are, again, at the edge. Inequality’s radioactive sludge has seeped into every part of our culture, from Hulu’s Daisy Buchanans to the acid bath of our politics. Our choice now isn’t between inequality and justice; it’s between justice and collapse. We can’t afford to choose wrong.

September 15, 2025

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time