Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

I spent the weekend in a cabin just south of Breckenridge that appeared to be constructed with Lincoln Logs. It was a gumdrop surrounded by towering fir trees, the lighting soft and warm. Aspens tore peels of shimmering gold into the mountainside. Exploring the cabin’s cozy insides, I felt like one of the claymation figures in the Airbnb commercials, toddling silently between the rooms of a Colorado-themed diorama.

This quieting effect was its main appeal: the stripping away of street noise and the electromagnetic hum of a home office and all the neuroses that I’ve developed and stowed in my 1,200 square feet of Denver, where I have felt more than ever this year like I’m looping the same day, week, month, over and over again, each revolution faster than the last. I hoped this getaway would stop the spinning, like ejecting a hand from bed after one too many drinks to grope around for the ground and steady yourself. In this case, the hand was the whole self. When the usual suspects (sleep, walks, baths) stopped having the desired effect on my mood for longer than a couple of hours, two days off the grid was the hard reset that felt up to the task of restoring me for the final work sprint of the year. (This was before I realized that sleeping at an elevation of 11,000 feet implied mild hypoxia for the duration of our stay, but that’s showbiz, baby.)

Nobody enjoyed this more than Sam Cat.

That the Wi-Fi stopped working the first night felt like a cosmic joke. You said you wanted to disconnect, I chided myself, panic rising in my throat as I uselessly refreshed a Chrome tab that stubbornly bore the same “No internet” message below a pixelated dinosaur. But wasn’t that the entire point? To avoid, as Jia Tolentino characterized it earlier this year, the “device that makes me feel like I am strapped flat to the board of an unreal present: the past has vanished, the future is inconceivable, and my eyes are clamped open to view the endlessly resupplied now?”

Burnout’s spin cycle in an age when one could theoretically be sustained by a nonstop parade of front-door deliveries of (truly) any conceivable desire is—how do I put this?—humiliating. I imagine some ancestor freshly arrived at Ellis Island, knee-deep in a slurry of animal remains inside a rancid meatpacking plant for 18 hours each day, being confronted with a discomfiting vision: It’s their distant progeny (me!) pacing around a climate-controlled apartment in sweatpants, mumbling about something called a podcast and bemoaning an endless barrage of electronic mail and voter registration and parking tickets and doctors who don’t know why you sporadically wake in the middle of the night to vomit, but it sounds like chronic stress. Would they get back on the boat, assessing that it wasn’t worth it after all to guarantee the future of such a weak-willed dilettante?

Regardless of the cause, becoming a little unmoored has by now taken a recognizable shape. I become hyperfixated on some virtually useless commodity that symbolizes The Treat That Will Change Everything. Last week, an ASMR YouTube video was recommended to me which pledged 1 hour and 15 minutes of “Cozy Fall Pampering” with Trader Joe’s pumpkin-scented ephemera. I immediately began rationalizing why autumnal-themed foodstuffs were—obviously—my mental health’s missing link. How had I not seen it sooner? The answer was right in front of me! (Or, more accurately, across town at Trader Joe’s.) Eventually, I settled on a Thoreauvian compromise: the cabin.

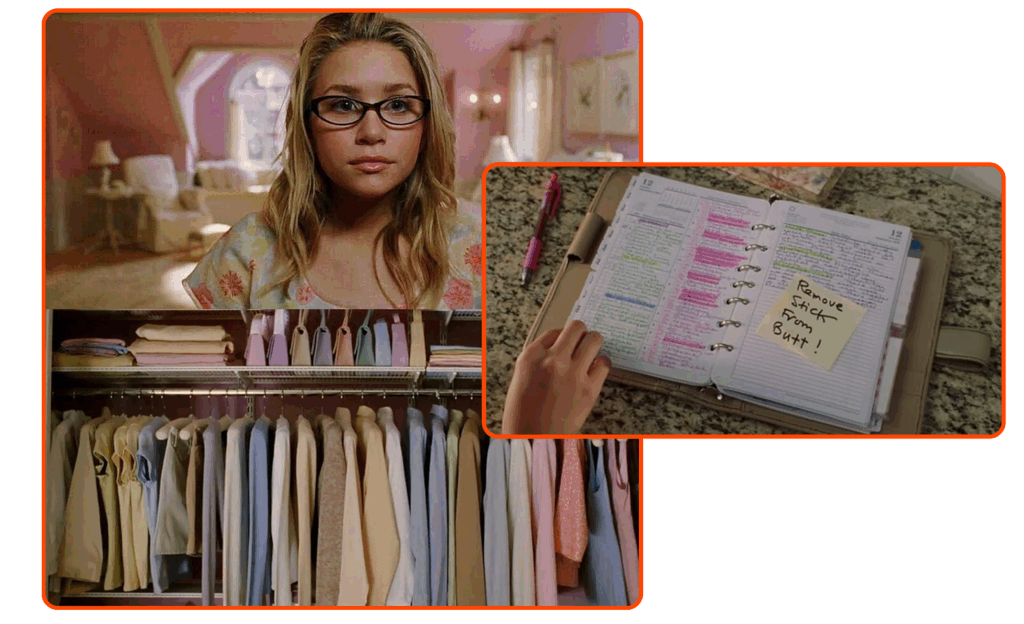

On the second night (after the internet was restored), we watched the 2024 erotic thriller Babygirl, a genre of film I generally refer to as a “sick f***” movie. (Used in a sentence: “That’s a movie for sick f***s!”) As far as kink plots go, it was actually fairly vanilla—an exploration of the popular fantasy that powerful, rich women secretly wish to be powerless and subjugated. The movie was ostensibly about consent, desire, and shame, but all I could focus on was what Nicole Kidman’s character, CEO Romy Mathis, was wearing. (Sexist!) For as long as I can remember, I’ve been reluctantly drawn to characters like hers, mistaking cautionary tales about caricatured strivers (and their color-coordinated schedules) for tutorials. You can put a woman in the woods, but you can’t make her stop fetishizing business formalwear.

The proto-Boss Babe, Ashley Olsen’s Jane Ryan. The moment she pulled back the double doors to reveal her closet in New York Minute (2004) was one of many Olsen-twin-facilitated formative memories. That daybook? Her note cards? Transcendent.

Pinning hopes for success on hypercompetent navigation of a modern economy is typical of the so-called professional-managerial class, a term coined by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in 1977 (or, in political theory, the “petite bourgeoisie,” a phrase which for some reason always makes me think of dainty finger sandwiches). It’s “the fantasy that financial anxiety and stress are temporary states of being that can be overcome through hard work, competition and education,” as Catherine Liu writes.

If Barbara were still alive, she might observe that the economic extremes plaguing the 2020s are merely the continuation of a process that began many years ago, when deindustrialization broadsided America’s working class. The rising sea levels of neoliberal policymaking have finally begun to meaningfully dampen the prospects of the professional-managerial class, who (maybe subconsciously) believed themselves to be more or less exempted from its worst offenses. Of course, she would probably tell us, that was never true. Because they, too, had to sell their labor, they were always “subject to the same pressures as other workers: deskilling, the weakening of their collective economic power, the degradation of the meaning of their work.” There is an implied lesson in this analysis that would suggest a change of course: The respites of self-help, hustle, and merit once assumed to reliably produce autonomy and fulfillment were a sleight of hand all along, which served only to “reproduc[e]… capitalist culture and class relations” and undermine any real chance at transformative solidarity.

Naturally, most financial media prefers to avoid class analysis, instead framing this ennui in terms of generation or gender. This provides narrative cover for dismissing structural strain by assigning it to the unique psychology of young people (or men, or women), rather than a legitimate force that exists outside TikTok.

Gen Z is, allegedly, rife with “financial nihilism” about the future. “Zoomers grew up with smartphones, the internet, and social media during difficult times like the 2008 economic crisis and Great Recession, and the subsequent Occupy Wall Street protest movement,” Fast Company offered last week in one unconvincing explanation. In this telling, it was not these crises themselves, but the crust of digital connectivity specific to Gen Z that shaped their preferences and disenchantments. “They’re disillusioned with traditional ways of doing things, which extends to how they invest and conduct their own finances,” the article explained. Back in January, Bloomberg warned that a “feminine” form of financial nihilism (read: find rich man) was ascendant. Over the summer, CNBC sympathized with “young speculators” so eager to “break out of the American caste system” that they had “embraced financial nihilism.”

The story has been exercised to the point of exhaustion by now. When there’s little hope that the traditional path will pan out as promised (student loans, unaffordable homes, wage stagnation, etc.), the metaphoric lottery ticket looks like a reasonable alternative. The scant proof of said nihilism is a stated interest in riskier investment behavior, like options trading or cryptocurrency or sports betting. (All products, it should be noted, with multibillion-dollar markets and marketing behind them.) Young women have given up on money and careers of their own in favor of mating up, the story goes; young men have given up altogether and turned to the slot machines of memecoins and DraftKings. The resultant impression is one of generational hopelessness and fatalism, a group so up to their eyeballs in trauma and trigger warnings that they’ve stopped trying en masse. But is it true?

An NBC poll conducted in August with Americans aged 18–29 found that young women and men had identical “top three” priorities in response to a question about personal definitions of success: Number one for both was “having a job or career you find fulfilling,” number two was “having enough money to do the things you want to do,” and in third place, “achieving financial independence,” ranking all three above things like spiritual fulfillment, community involvement, and family formation. Tellingly, this trend held true for presumably conservative young women, those who voted for Trump. These are not the priorities of people who have given up on their hopes of upward mobility, but those who are instead singularly focused on it.

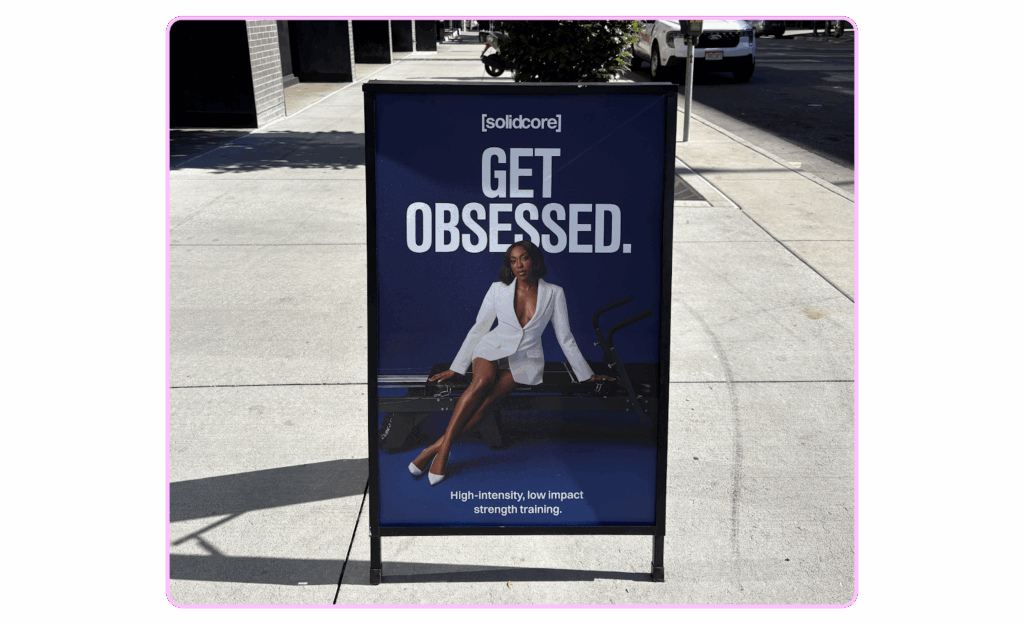

Once back in Denver and on the hunt for something I couldn’t buy in the woods (overpriced caffeine), I walked past a pilates studio with a sandwich board propped up at its entrance that commanded passersby to GET OBSESSED. The ad featured a striking woman (SNL’s Ego Nwodim, it turns out), all glowy sinew and smolder, perched cherry-like atop a pilates reformer. Implausibly, she was wearing a sleek white blazer and matching stilettos. I paused in front of the sign, sustaining eye contact, waiting to feel something like cynicism or annoyance with the dated Sexy Corporate Empowerment trope. It felt like a relic of (pre-election) 2016, when peak modern womanhood was mostly tantamount to group exercise and Revolve suits.

Shipwrecked on the sidewalk, it was not cynicism I felt, but a confusing, wistful longing. It wasn’t that I missed the pre-pandemic years, per se—when I would take an hour-long fitness class at six in the morning, five days a week, before spending 10 hours in heels and hard pants—so much as I missed when such things sounded not only like reasonable ways to spend one’s time, but fun. Back then, ambition still felt clean and moral; its challenges seemed to be accruing to something meaningful.

My mind immediately flashed again to Kidman’s character in Babygirl, all low chignons and high-neck blouses (“Another serve,” my husband joked approvingly when she appeared on screen in ‘fit after impeccable ‘fit), and how competent and controlled she seemed before her proclivities—and all that lactose—derailed her to the point of taking tousled weekday couch naps next to open jars of peanut butter on the floor, the universal distress signal for Not Thriving. (When she appeared again behind her desk at the end of the film reassembled in dignified workwear, I was embarrassed to feel palpable relief.)

The presence of these women in my weekend—the fictional Romy Mathis, the real Ego Nwodin—seemed significant, somehow, like an inadvertent girlboss revivalism. They appeared to inhabit a different world entirely, one in which constant self-discipline and hypercompetence was not only still possible, but glamorous and effective.

Such aspirational displays must be understood not as drivers of a culture that’s been subsumed and defined by its economic system, but as responses to it. Nostalgia is a potent force both individually and nationally; some imagined, simpler past with cheaper homes and Chainsmokers songs and fewer breaking news push notifications. Normally, the era most effectively wielded in American politics to prescribe cultural shifts is the 1950s. But what does it mean to privately indulge in nostalgia for the 2010s, a time that felt comparatively hopeful? What to make of the fact that, regardless of the lofty class analysis, I still feel better when I’m trying?

For the professional-managerial aspirants, the 2010s were all about startups, self-help, and striving—a path that, by the following decade, was widely understood and mocked as an individualist dead end; the Ehrenreichs’ 1977 prediction seemingly coming true. But for all the talk of nihilism and hopelessness, the pilates class I could see through the windows was full.

September 29, 2025

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time