Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

Love Is Blind season 9 contestant “Sparkle” Megan Walerius says men are intimidated by her.

In her own words: “I’ve done very well for myself professionally. I think it takes a very confident and secure man to be with a woman like me. It’s going to be interesting to navigate, are they just after me for money or is it me for who I am?” As Gwen Stefani’s “Rich Girl” plays in the background, Megan confides in her first confessional that she’s still single because some men are put off by “how I live, my level of success, the car I drive, the house I live in.” The camera leers at her various accessories in heavy-handed tight shots on her sparkly shoes, a thin diamond bracelet on one wrist, and a stack of gold jewelry on the other, each punctuated by a “cha-ching” sound. We are a mere 16 minutes and 47 seconds into episode one, and the editing has already illustrated Megan with all the nuance of a bedazzled LinkedIn manifesto.

This sets up the viewer for contradiction-induced vertigo when, moments later during one of her first dates, a real estate investor named Mike asks if his leaving a bunch of dirty dishes on the counter would make her mad. (Has this man never had roommates?) She hesitates. After eking out a high-pitched ummmmm, she sidesteps this trapdoor by widening her scope to abstraction. “It would annoy me, for sure, but I’m also…I kind of believe in more traditional gender roles.” His barely concealed excitement at this disclosure, accompanied by eyebrows raised in pleasant surprise and a jaunty hand-on-hip, is the okayyyy! heard ‘round the pods.

“That’s why I’m kind of an anomaly,” she hurriedly explains, “because, yes, I’ve had an amazing career, but I also value, you know, the woman being that nurturer, and I definitely want my man to be kind of ‘the provider’…like, the security and the safety. I think there’s something to be said about a man who’s like, ‘Yeah, I want to take care of my woman.’”

Mike, who moves like a man always on the precipice of soft-pitching a startup, would appear at first blush to fit this bill (but at what cost?). In a later date, he careens through an explanation of his own financial position in “this larger…we call it a tribe, but it’s a national thing. A bunch of guys that are wealthy are a part of it.” (In real bullet-dodging fashion, Megan ends up choosing a guy named Jordan, who lists the reasons he likes her in his own confessional—“confident,” “independent,” “strong”—though she registers early concerns about their “lifestyles meshing,” presumably referencing her success relative to his.)

Money has always been a phantom contestant on Love Is Blind, a series that debuted a genuinely novel dating show premise in 2020. Still, season nine seemed to be making a point. Having barely just recovered from Megan and Mike’s asset management summit date, we are confronted again by its presence minutes later when another contestant named Anton plucks a similar chord in one of his first dates with a healthcare professional named Ali. “I’ve built my business. I’ve bought my first house when I was really young. I’ve done well for myself, and I’m the provider. I’m very, like, old-school, traditional, in terms of how I treat women.” There are those words again: provider; traditional. (In a later episode, Ali and Anton—having chosen to get engaged—playfully debate how much he should’ve spent on her ring. He says $5,000, she doubles his money and goes for $10,000. The gag is that production buys the rings; the contestants pay nothing.)

These interactions present a real hammer–nail conundrum for a viewer in my line of work, which requires being painfully aware of the gendered labor statistics economists have been firing off for the last two decades like unheeded distress flares, a sad fireworks display of futile awareness. Heterosexual couples in which the woman is the primary earner are the only “type” in time-use research where the primary earner also spends more time on “home production” tasks. A 2025 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper found that “[i]n every other couple type—heterosexual couples with male breadwinners, lesbian couples, and gay couples—the breadwinner spends less time on home production than the non-breadwinner,” taking care to point out that “this is driven not by childcare” (which could ostensibly carry some genuine biological limitations early on) but rather “chores like food preparation and cleaning.”

By the time Kalybriah asks Edmond if he’s looking for a “traditional or non-traditional marriage,” I braced for impact—all but certain this was an intentional theme of the episode—but Edmond’s answer (“definitely non-traditional”) takes the conversation to new and welcome territory. Kalybriah agrees. “I’m okay if I’m the breadwinner; I’m okay if my husband’s the breadwinner. I’m okay if I cook; I’m okay if my husband cooks.” At this, Edmond and I both engaged in private celebration.

One fair read of all this posturing is that when educated, high-income women say “provider,” what they really mean is contributor—someone who isn’t a net-drag on their resources. Another is that it’s serving a different purpose altogether: subtly setting expectations about physical appearance.

Allow me to explain: The meet-your-soulmate-through-a-wall format has given way to a few predictable tropes. One of my favorite reviews of the show named the bombastic flirting style—“Hot Person vibes”—of the contestants who “spend lots of money (on clothes, on cosmetic procedures) and time (at the gym, at the club) with the express goal of being seen,” which is often subconsciously perceptible to the person on the other side of the wall. “A Hot Person doesn’t have to sell themself; they’re operating under an assumption that they are desired,” Emily Palmer Heller writes, even when they cannot be seen. This observation, I thought, was brilliant. The paths of inquiry this reality has given us—like all the creative ways the men try to assess whether a woman is thin (“Could I put you on my shoulders at a concert?”)—reveal many techniques for deducing whether someone is your “type” that don’t immediately scan as overtly about looks.

But it was only in watching season nine, episode one, that I finally recognized a new line of questioning (and calculated self-revelation) that seemed to hint at the same: asserting an approval of so-called “traditional” gender dynamics, a choreography so committed to our cultural muscle memory that it’s easy to forget it’s less about dollars than desirability. Broadcasting your embrace of this arrangement is really about signaling femininity—and femininity, to bastardize the Miranda July line, is really just beauty.

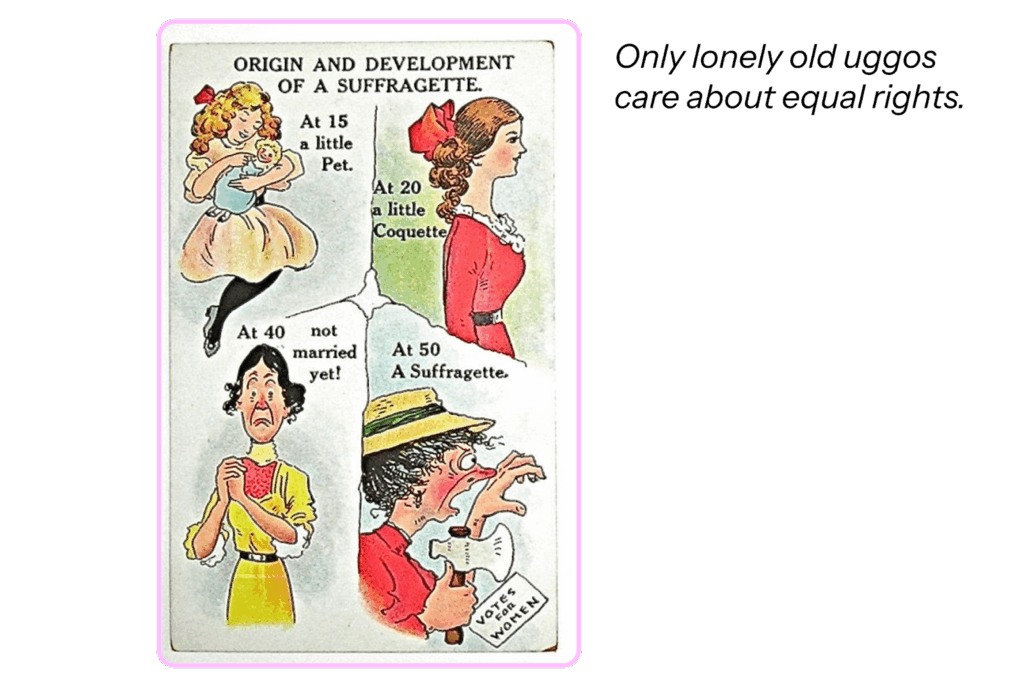

Since the beginning of the women’s rights movement, the political avatar for a woman who challenges gender roles has been The Feminist, or a person who believes in—and I suppose this is my working definition—liberation from a biological narrowing of your humanity. Since the 19th century, feminists have been portrayed as unattractive, masculine “hags,” fighting for something “unnatural” (equal rights under the law).

The right to vote, pay equity, and egalitarian partnerships are things that hot chicks don’t want, you see, because their beauty allows them to access something far superior to all that noise: a doting husband with money. This is the implicit trade. The savvy leaders of the suffrage movement knew this, and as such, embraced “feminine” presentation in public and in propaganda to defuse the politically noxious bomb that women who wanted equality were, either as a result or inciting factor, ugly—the worst thing a woman can be.

In a recent episode of Diabolical Lies that analyzed how modern misunderstandings of “tradition” inform reactionary beliefs about gender, I played a six-month-old clip for my cohost in which the late Charlie Kirk and his wife Erika discuss the proper roles for men and women in marriage. “How much did you guys discuss religion, finances, politics, how to raise children, before getting engaged?” a listener asked. Charlie zeroes in on finances, then addresses his male listeners directly: “Men, you should be completely in charge of finances.” Somewhat bewilderingly given her role as the founder and ostensible owner of two companies, Erika emphatically agrees. Charlie continues: “Your wife should have nothing to do with it. I mean, they can have input, but you should release that burden from your wife and just take care of all the money.”

A couple of minutes later, buoyed by her support, Charlie doubles down, this time addressing his female listeners: “If you are marrying a man that is not capable of completely and totally handing the finances, then you should not marry that man.” At this, she lightly pushes back, but he insists that a marriage in which women financially participate by earning or managing money is unnatural; a fiscal manifestation of “confused gender roles” which spells disaster for the fragile arrangement of heterosexual monogamy, its stability forever hanging in the balance of invisible, highly specific rules about whether it’s gay to do your own laundry. The woman’s proper role in all of this, they agree, is what they call (but, it’s worth noting, struggle to coherently define) “submission.” Tellingly, part of what submission entails, Erika explains, is “…you need to take care of yourself in order to…you can’t be looking like Adam Sandler and expect that you’re going to…” We never find out what we shouldn’t expect if we indulge the slapstick aesthetic of basketball shorts and Hawaiian shirts, because here, Charlie interrupts to tell the men that, for them, success in love comes down to “just figur[ing] out ways to make more money.”

After reviewing a few more examples from similar programming, my cohost, novelist Caro Claire Burke, clocked the bottom line of this rhetorical maneuvering. “They use terms like soft and feminine and submissive,” antonyms for the masculine, traditional provider archetype, “but what they’re really talking about is pretty. You have to be pretty.” In that sense, a female Love Is Blind candidate who’s comfortable demanding that her partner offer masculine power and provision is, in a roundabout way, hinting at her own adherence to a woman’s role in this quid pro quo: beauty.

To be sure, I don’t believe these contestants are doing this purposely or deceptively—on the contrary, we’re all so fluent in this cultural script (feminists ugly, submissive young brides pretty) that it usually evades conscious recognition altogether. When Anton says he believes a man should be a provider and casts himself as such, he is not just stating a preference for how household finances are handled (though he will later express hesitation about Ali having her own bank account)—he is issuing a tacit expectation that he is met in this transaction by a woman who understands her role to “not look like Adam Sandler,” as Erika put it. Fortunately for him, Ali is a smokeshow with a job; it remains to be seen whether Anton makes a commensurate amount of money.

More instructively, this interpretation translates Megan’s seemingly incongruous statements about her lifestyle and belief system into something more legible. She does not actually wish to become a stay-at-home wife with an allowance. She just wants Mike to know she’s hot. (“I’m just very drawn to Mike,” she says privately, stating the obvious. “I want to build an empire with someone, and I think he would be a great person to do it with”—not exactly the language of a gal hoping to hang up the old Slack account.) In a dating environment where the power of one’s looks are totally neutralized, it’s no wonder this sort of antiquated shorthand becomes a crutch for communicating something as clumsy as desire.

These desires are, of course, shaped by what’s happening outside the pods. This includes the broader economic reality of the 2020s, which might clarify the urgency of the contestants’ task to get married to someone they met a month ago. In her 2006 essay “American Nightmare,” political theorist Wendy Brown sketches the relationship between neoliberal economic principles (read: what the kids call “late-stage capitalism”) and social conservatism (read: Charlie Kirk telling young men not to get married unless they earn enough money to support a family). In modern life, the mythic “male provider–female nurturer” dynamic is positioned like a comforting antidote to the very real challenges of an unforgiving society that constructs “governance according to market criteria.” The genius of Brown’s essay and the book it later appeared to inspire, Melinda Cooper’s 2017 Family Values, is that they expose how these two powerful forces are not countervailing, but conspiring.

In other words, it’s difficult to discern where a romantic imperative blurs into an economic one: A 2023 paper from the Federal Reserve of Dallas found that a version of the US where marriage did not exist would see prime-age male work hours decline by 7%. Is this because, without the prospect of marriage (“just figuring out ways to make more money” to get a girlfriend), men wouldn’t work as much? Or because once they’re married (per the time-use data), they have more time or incentive for work? The direction of the correlation is not conclusive, but the data suggests the economic powers that be would have a reasonable vested interest in Anton saying “yes” at the altar.

In episode eight, after touring a $2 million home with his new fiancée Sparkle Megan, a visibly uncomfortable Jordan equivocates: “I don’t think she’ll ever feel like I’m mooching,” he explains, “but I feel like a mooch, you know? The fact that she’s just talking about buying a house for us, and she’s like, ‘I’ll take care of it, don’t worry about it.’ I think that’d be hard for any blue-collar guy to absorb, because I’ve always been the provider, and now someone’s stepping in.” It’s satisfying to watch these two people process the friction of transgressing their “roles” in real time, particularly because we know if the situation were reversed, asymmetric financial success would be nothing more than a happy ending. “But I don’t want her to be stepping down, and like, maybe not living the life she wants as a compromise to be with me,” he continues, before appearing to reclaim the word that’s been so freighted up until that point: “So I want to make her feel at home, and be a provider for her, too.”

October 14, 2025

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time