Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

In the fall of my senior year at my all-girl Catholic high school, we went on a mandated retreat. It was hosted at St. Anne Convent in Melbourne, Kentucky, the location where they shot the movie Rain Man, something they inexplicably reminded us throughout the weekend.

The weekend-long retreat was designed to manufacture vulnerability: We’d sit in a circle and take turns confessing our sins (?) and revealing traumatic experiences to our peers (?!), then pray. It had the forced togetherness, fun, and intimacy of a large sleepover, but with the uneasy, looming presence of authority figures.

It all culminated on the final evening with a demonstration led by a young man, who instructed us to pass a rose around. We were told to touch the petals as we examined it, and all the while, he lectured us about sexual purity.

>

“By the time the rose made it back to the front of the room, it was greasy and wilted, having passed through dozens of Cheeto-dusted fingers.”

By the time the rose made it back to the front of the room, it was greasy and wilted, having passed through dozens of Cheeto-dusted fingers. “This,” he exclaimed, holding up the soggy flower, “is what happens to you when you have multiple sexual partners.” (The physics of how the same person touching the petals over and over again wouldn’t similarly disfigure the flower was a plot hole in this analogy that he never addressed.)

Predictably, girls around the room stared wide-eyed at the slimy, disintegrating mess that supposedly represented their desirability and worthiness post-fornication at last year’s junior prom. Then they burst into tears.

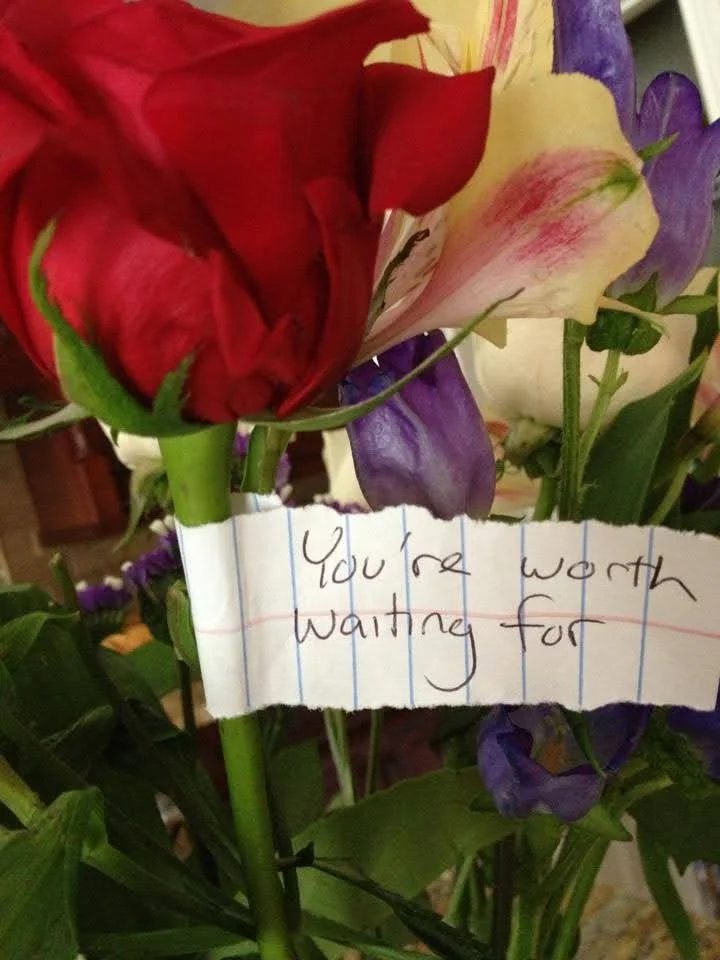

He closed his session by handing out fresh roses with haphazardly torn pieces of notebook paper affixed that read in scratchy, boy handwriting, “You’re worth waiting for.” Gee, thanks, Garrett.

I didn’t tell my parents about these experiences or talk to anyone outside of these classrooms about them. In retrospect, this message struck me as so horrifyingly problematic that I wasn’t sure if it was a fever dream I conjured from watching too much 19 Kids and Counting, but I recently scoured my Facebook archives and found this in an album called “Homecoming 2012 and Senior Retreat”:

Federally funded abstinence-only messaging and the “true love waits” movement began infiltrating even secular high schools in 1996, but we got the radioactive version in Catholic school. It’s well-documented now that purity culture—the religious emphasis on a woman’s virginity as part of her value and sanctity—creates a psychological minefield. (I asked my husband, who went to an Episcopalian all-boy school, if he received any such education around his sexual purity, and he stared back at me, blinking slowly, before replying, “No…?”)

We know that teaching adolescent women that sexuality is shameful and dirty makes it physiologically challenging for them to suddenly embrace the thing that supposedly defiles their virtue, even within the context where it’s permissible (i.e., marriage).

I’ve been thinking recently about the way mainstream personal finance approaches spending money in a parallel way—purity finance, if you will. Spending is something you should only enjoy once you’re already wealthy, and until then, it’s the enemy of financial prudence. Perhaps the most famous personal finance educator in the world, Dave Ramsey, is quoted saying, “If you’re having financial issues, the only time you should see the inside of a restaurant is if you’re working there.” His radio show reportedly has 14 million listeners each week.

Most of our perceptions around being “good” with money involve a moralized framework that positions saving as virtuous (and, by extension, spending as something to do as infrequently, minimally, and attentively as possible). Overpaying for something is heresy. Debt is the gravest sin.

I can’t even count the number of conversations I’ve had in recent years with very wealthy individuals—those with net worths in the multi-millions—who now struggle to spend money on anything because they’ve adopted ultra-frugal saving as a core tenet of what it means to be “good,” or at the very least, “good with money.”

We’re accustomed to denigrating those who blow through every cent that enters their checking account, but we rarely pathologize the person who’s worth $5 million and still comparison-shops for strawberries.

When you believe for your entire working life that saving money is “good” and spending money is “bad,” the idea that you’ll be able to abruptly throw it in reverse and spend freely upon entering retirement is not a realistic expectation. Even though you now occupy the context in which spending is sanctioned in this framework (the very thing you’ve been saving for!), the connection between spending and irresponsibility is often too entrenched.

Purity finance operates from a default posture of control, which assumes people are incapable of holding two truths at once: that saving for the future is important, and spending enthusiastically on things you value is healthy.

What’s not healthy is a religion of fear-based, rampant accumulation, or guiltily refracting every purchase through the lens of a compound interest calculator like a gal with the threat of a Cheeto dust-covered perennial hanging over her head. The irony is that, in an effort to carefully preserve something for future enjoyment (whether that be sexual “purity” in marriage or the largest nest egg possible for retirement), you inadvertently internalize a message that damages your ability to ever enjoy it.

I noticed recently that each “tap” of my AmEx brings with it vague pangs of guilt, regardless of what I’m buying. To combat this, I’m focusing on reorienting my internal editorializing of my purchases the moment I make them. Rather than, Wow, $110? This is only four days of food, it’s, I’m so excited about these groceries; they’re going to make such good meals this week. Rather than, Ugh, professional help is expensive…is this wasteful? it’s, I’m so happy I get to support this woman’s business; she’s helping me live a better life.

A thriving relationship with money requires an ability to save for Future You and freely invest in Present You, because you’ll only ever experience your connection with money in the present—as Eckhart Tolle writes, “the future never comes.”

February 26, 2024

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time