Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

The surgeon general’s pop-up shop, Robert Iger’s face

Discount Etsy agitprop, Bugles’ take on race

Female Colonel Sanders, easy answers, civil war

The whole world at your fingertips, the ocean at your door

The live-action Lion King, the Pepsi Halftime Show

Twenty-thousand years of this, seven more* to go

Carpool Karaoke, Steve Aoki, Logan Paul

A gift shop at the gun range, a mass shooting at the mall

—That Funny Feeling (2021)

Four years ago, Bo Burnham wrote a campfire song for the end of the world. The broken jukebox in my mind has been playing the song on a loop for the last two weeks, the lyrics surfacing intermittently as my daily life provided material for new verses. There were moments like attempting to get wrinkles out of a hot pink suit before an upbeat livestreamed event about women’s financial independence; watching a livestream of a mother being dragged into an unmarked van by two masked men as her screaming child looks on in a discount grocery store parking lot. A family playfully arguing about which ice cream flavor is superior at the shop in my neighborhood; B-52 bombers “being moved into position” in my push notifications. New seasons of Secret Lives of Mormon Wives and America’s Sweethearts (when to binge?!); news story about an Australian national being detained and deported for his Substack posts about the Columbia protests.

Finally, I was greeted by one of my dinner companions upon returning from a phone-free bathroom break Saturday evening at an upscale restaurant to learn that, in the time it took to flush away $7.50 worth of mocktail, the world had changed: “We just bombed Iran.”

There it is again: that funny feeling. To live in the United States today is to exist in an accelerating state of contradiction, to be surrounded by entertainment and creature comforts as you feel tectonic plates shifting uneasily beneath your feet. Of course, this state of affairs is still preferable to living in one of the countries currently experiencing the explosive fruits of our tax revenues, where there is no time for the luxury of detached bewilderment, only the charred smell of terror.

A meme that somehow only ever becomes more true.

There’s a Russian word—hypernormalization—for this funny feeling. It describes the uncanny psychological experience of continuing to make your bed and drive your children to school and show up for work amid a creeping sense of breakdown. In a review of an obscure film published in The New Yorker just days before the 2016 election, Brandon Harris wrote that “during the final days of Russian communism, the Soviet system had been so successful at propagandizing itself, at restricting the consideration of possible alternatives, that no one within Russian society, be they politicians or journalists, academics or citizens, could conceive of anything but the status quo until it was far too late to avoid the collapse of the old order.” The end of their country was, for the Russian people, “both unsurprising and unforeseen.”

During such periods, depression or anxiety are rational reactions to engaging honestly with reality, and coping can manifest in strange, trivial ways. When the shape of ordinary life feels inconsequential and surreal, little luxuries start to feel like lifelines. I’ve been preoccupied lately with whether I should schedule a manicure, hyperfixating on the psychological safety of milky pink gel nails provided by a salon located in an alternate universe wherein choosing something as frivolous as a nail color, like an ice cream flavor, might feel worthy of my attention. Like any good American, I apply consumption like a balm over the spiritual burns I sustain from witnessing the fires we keep lighting, whether in Tehran or Los Angeles. Indulging feelings of guilt or rage about this state of affairs feels inane, an emotional simulation of “doing something” without having to interrupt a doomscroll.

How did Hegseth’s group text respond to the update? I wondered privately at dinner as the conversation around me shifted to the plot of a new animated movie about a cat. I imagined the parade of closed yellow fists and American flags and fire emojis dancing across the screens of our appointed officials. Later that night at home, I watched CNN as if caught in a time warp. The coverage pivoted quickly from shock to justification, repeating an eerily familiar narrative about nuclear weapons and the “complicated” nature of our involvement in yet another conflict in the Middle East—bombing for safety, war for peace.

There are lies, damn lies, and US officials making Powerpoint presentations to the United Nations Security Council.

The echoes of US history, both recent and ancient, are so loud that highlighting specific similarities feels unnecessary—overthrowing foreign governments that are less than expedient to our economic interests is a cherished American pastime. What’s noteworthy now is not what we’re doing, but the fractured, distorted way in which we’re experiencing it this time around.

In March 2003, when we invaded Iraq because the country’s military had “weapons of mass destruction” (they did not, as Bush, Cheney, and Powell well knew), I was in second grade. I wrote a poem, rendered in Comic Sans, called “The War in IRAQ,” in which I implored my classmates to “raise money for the president,” “pray,” and “wear red, white, and blue.” The manufactured consent in these situations—that which gets 8-year-old girls penning patriotic haikus about the Bush administration—relies on an abstraction of what war really is. In 2004 when images emerged from Abu Ghraib of US troops abusing Iraqi prisoners, the number of Americans who reported they felt the war was going “fairly well” dropped below 50% for the first time. Confronting the unspeakable truth made Americans think twice about whether we supported our country’s vast resources being used in this way.

But that sort of moral confrontation was rare, made possible by the fact that, until relatively recently, the atrocities were mostly happening on another continent, out of sight from our cookouts and Friday night lights—a distance just wide enough to wedge the bulky solace of our plausible deniability. By the time the details reached our TVs, US news networks had already impersonalized them with language about “strikes” and “targets” and “retaliation.” Now, we are accosted with these horrors, foreign and domestic, every time we open Instagram to post a picture of an outstretched hand bearing a fresh gel manicure, the dissonance reverberating louder.

More than 20 years after the invasion of Iraq, a conflict which claimed $3 trillion and more than 500,000 Iraqi lives, it feels like whatever semblance of a collective plot we once maintained was fed into the internet’s meat grinder, churning out a rotting pile of hotdog meat that is, somehow, much dumber. After a journalist was added to an illicit Signal chat in March, the lion’s share of coverage focused on the offensive procedural faux pas. The contents of the messages—including the revelation that we had blown up an entire apartment complex in the hopes of killing a single person—were treated like an afterthought in the coverage, a distant second concern to the breach of communications protocol. There it is yet again: that funny feeling. Accountability, where we cared, focused mainly on ensuring we celebrated our state-sanctioned destruction via the proper channels next time. (“We used to make real national security psychopaths in this country!”) Within days, it was a meme fashioned after a Buzzfeed quiz: “Which Houthi PC Small Group member are you?”

What does it mean to lose the ability to be horrified, or worse, to lose the capacity to imagine a version of this country that doesn’t wield its wealth and power this way? While the baldly sensationalized stories on Fox News are the traveling carnival version of the American identity industrial complex, the versions you’ll find in liberal publications are arguably more insidious, because they so effectively position themselves not as the bigoted drunk uncle at Thanksgiving, but The Serious Adults in the Room.

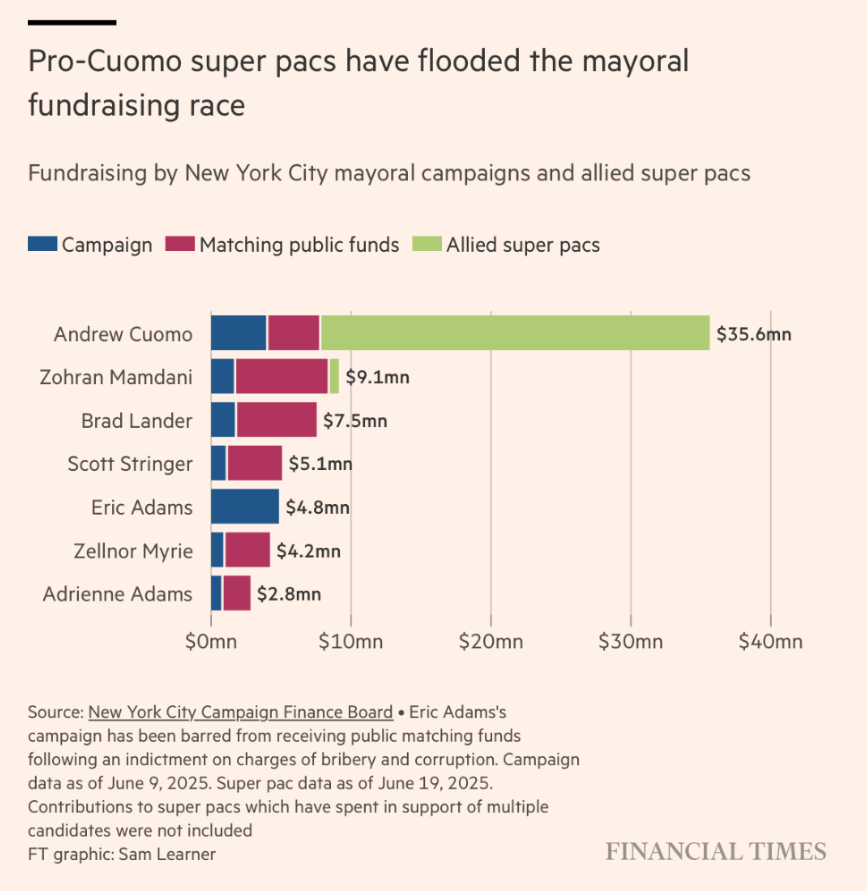

Consider the recent coverage of progressive New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani across a stunning number of liberal newspapers and magazines: Mamdani’s platform—which includes things like free city buses, childcare for all, and a public option for grocery stores in lieu of subsidies for private ones, all made possible by matching New Jersey’s corporate tax rate and instituting a flat 2% tax on annual incomes of more than $1 million—is presented almost uniformly as dangerous and radical. The flurry of op-eds fuse the art of elite opinion-laundering with brute force super PAC money to explain why Mamdani’s vision is unserious, reckless, and worse yet, naïve. Never mind the groundswell of desperate support to try something different! One learns that to be a Sensible Liberal, one should instead vote for the three special interest groups in an Armani trench coat (read: Cuomo) who would never propose something as fanatical and upsetting as a 2% tax on investment bankers.

But as any American within striking distance of a critical thought is incessantly reminded, the US is a democracy (unlike all those countries in the Middle East!), where speech is free and money is speech and politics is a game best played without consequences: According to the Financial Times, “Campaign donations showed the city’s billionaire elite was determined to halt [Mamdani’s] rise,” amassing an “unprecedented” amount of money for Cuomo, a man who resigned in disgrace from his post as governor just four years ago.

What were the conditions for hypernormalization again? “The Soviet system had been so successful at propagandizing itself, at restricting the consideration of possible alternatives, that no one could conceive of anything but the status quo until it was far too late to avoid the collapse of the old order.”

Maybe all this talk of collapsing orders feels dramatic; if so, blame my recent reading of Ray Dalio’s new book, How Countries Go Broke, in preparation for a conversation on Friday. In it, he estimates the chances of “an unwanted major [financial] restructuring” (a friendlier way of saying “default on our national debt,” from what I can gather) at around 80% over the next decade if nothing is done to reverse our fiscal and geopolitical course. This is, of course, assuming the Big Beautiful Bill—set to add another $3–$5 trillion in deficit spending—doesn’t pass the Senate. Dalio’s alarm is thinly veiled but palpable in these pages, as it’s clear he sees us marching in the exact wrong direction of the bipartisan consensus we need to avoid catastrophe.

Dalio wrote the book and made these calculations before ICE raids began in earnest, the economic consequences of which will almost certainly compound the effects of any new deficit spending in the form of slower growth and lower tax revenues. The raiding of workplaces and immigration courts and elementary school graduations has been the most affecting policy instituted so far, because unlike that which can be avoided online by closing an app or climbing into a different echo chamber, it’s hard to ignore someone being dragged out of the Home Depot where you’re perusing paint chips for a nursery. It appears to be the rare Trump policy that appeals to a subcutaneous layer of humanity still untainted by Fox News-induced psychosis—people are, perhaps naïvely, surprised when their friends and neighbors are targeted by ICE, shaking confidence in a simplistic narrative about roving bands of “illegal alien criminals,” a fear-inducing turn of phrase repeated with such relentless enthusiasm on the campaign trail it calls to mind the early aughts fixation with “terrorist enemy combatants.”

The difficulty of engaging with any of this as it unfolds—whether bombs dropped abroad or neighbors detained at home or a media apparatus committed to playing nose tackle for Wall Street billionaires—is not just about the discomfort of witnessing suffering, but confronting the reality that to be American is to actively benefit from injustice. That confrontation would implicate everyone who gains from social programs that undocumented people pay for but cannot use ($25.7 billion in Social Security taxes in 2022 alone); everyone whose retirement relies on the performance of an S&P 500 index fund that will inevitably surge from the successful voyage of Northrop Grumman’s ($NOC) B-2 bomber.

A 2025 Brown University report estimated US-sponsored violence in the Middle East since 2001—committed in the name of liberty and justice for all—cost $8 trillion and has killed between 4.5 million and 4.7 million people. That Donald Trump has managed to convince so many Americans that we are the ultimate victims in this global order is a stunning inversion of reality, sure, but it’s also narratively consistent for a nation that’s always been addicted to its fictions, impressively adept at “propagandizing itself.”

The funny feeling is what seeps through the cracks of that crumbling facade, a glimmer of the country we know we could be if we were brave enough to look.

*Discerning readers will notice that the 2021 lyric “seven more [years] to go” would indicate we’ve got about three left.

June 23, 2025

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time