Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

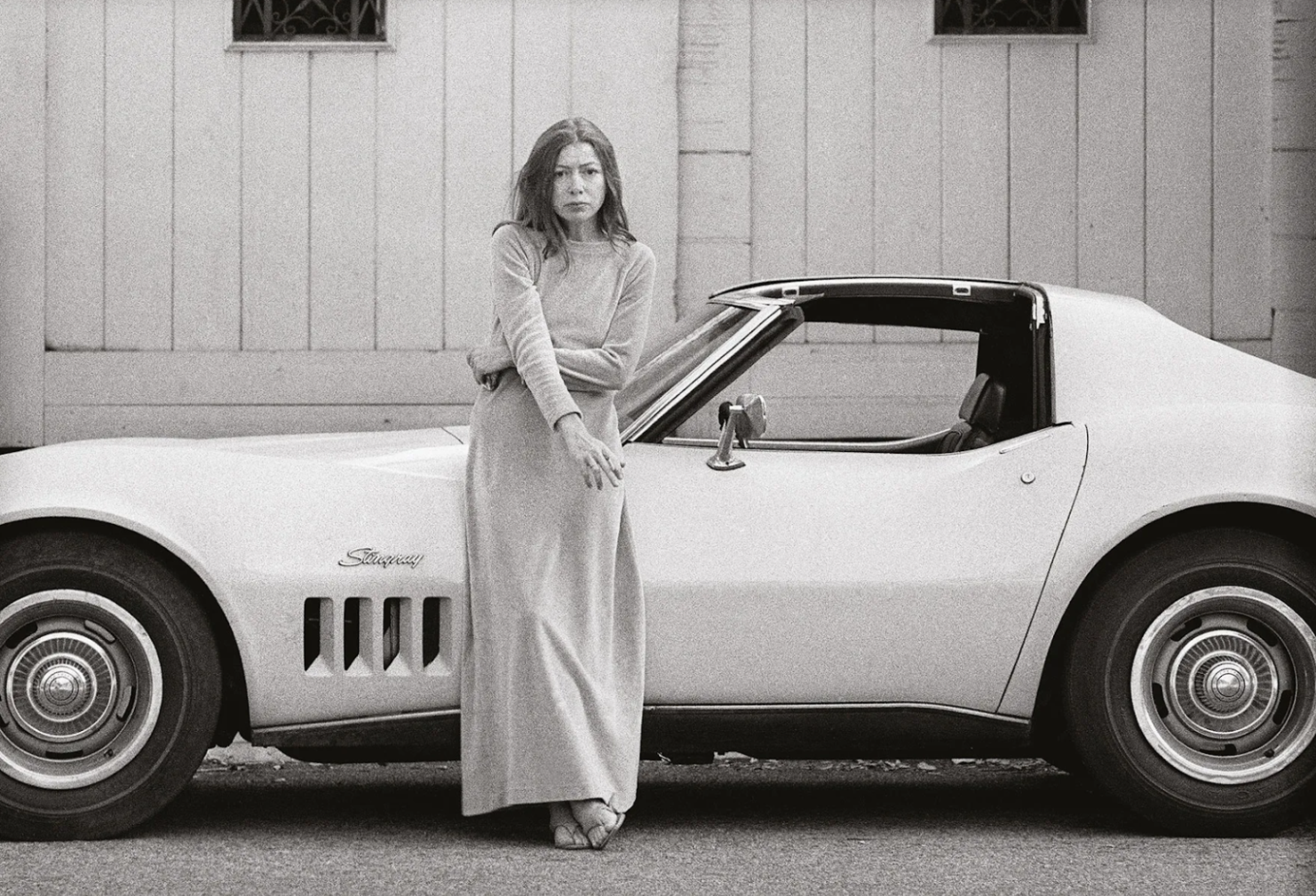

As the S&P 500 continues to creep perilously higher with each passing week of 2025, I’ve been reading a lot about AI and thinking equally as much about the late Joan Didion, one of the most famous women in the grand tradition of putting words on paper. This may seem a strange, spontaneous association, but her ruthless insistence on rejecting comforting American myths made me want to revisit her work in the context of AI speculation. Her own decades-long political evolution provides a useful case study in navigating accepted narratives, although it’s certainly a less sexy element of her legend than the iconic photograph leaning on her Stingray, cigarette dangling idly between slender fingers.

Is it any wonder this person scored a CELINE campaign?

While every cool progressive young woman today uses her Ruth Bader Ginsberg bobblehead as a bookend for the Didion shelf of her bookcase, Didion launched her career at the conservative magazine National Review. (The publication was founded by none other than William F. Buckley, a man considered the architect of the modern conservative movement.) Her own conservatism was, as Sam Adler-Bell put it, “very invested in complexity and rejecting the liberal belief in easy answers; the idea that human nature can be reduced to solvable social problems.” It was former President Ronald Reagan who eventually turned her against the party, though you get the sense it was less that she disagreed with his politics and more that she found the whole Reagan family to be unbearably tacky. “Had Goldwater remained the same age and continued running,” she wrote in 2001, “I would have voted for him in every election thereafter.”

Considering her upbringing among “conservative California Republicans,” this checks out. But when you live by the pen, you change by the pen. She eventually turned her signature, unsparing method—“no lying, no self-soothing delusions, no aspiring toward innocence in the face of evidence of culpability”—on herself. This emerges most stridently in a book she published when she was 68 called Where I Was From, which is ostensibly about the history of California but ends up functioning as a record of personal disillusionment with the state’s blinkered origin story and, to a certain reader, American exceptionalism more broadly.

In it, she systematically juxtaposes her own ancestors’ self-styled bootstrappy California landfall—traveling with the infamous Donner-Reed Party, but escaping their cannibalistic fate by, poetically, refusing to take a shortcut—with the realities of early land distribution. Describing how California was originally parceled out, she observes that land was “largely acquired through imaginative interpretation of the small print in federal legislation.” She unceremoniously lists the various loopholes which allowed for “subsidized monopolization” among a few wealthy landowners and railroad companies. (One such provision deemed any land relegated as “swamp” to be essentially handed out for free by the hundreds of thousands of acres, which led to a curious reclassification of vast tracts of the state.)

A reinvention of this history, she writes, tends to carefully trim off the unsightly fat of federal government largesse in the amassing (or destruction) of private fortunes. “Stressing as it did an extreme if ungrounded individualism, this was not an ambiance that tended toward a view of life as defined or limited or controlled, or even in any way affected, by the social and economic structures of the larger world,” she writes of early California myth-making. The implication is unavoidable: Where she once identified with an imagined, exceptional group of rugged frontierspeople determined to do whatever it took, she now sees plot holes that demand a rewrite.

Speaking about the policies that created Southern California’s broad consumer middle class in the late twentieth century, she manages to sneak in more than a little class analysis, most memorably in the chapters about the disquieting economic ripple effects of hundreds of thousands of aerospace industry layoffs in Los Angeles county in the 1980s and 1990s. “What does it cost to create and maintain an artificial ownership class?” she asks of the communities whose work had been furnished by federal defense contracts. “Who pays? Who benefits?” Then, a devastating addition: “What happens when that class stops being useful?”

In 2025, that insistent “larger world” with all its “social and economic structures” seems to be closing in on our “extreme if ungrounded individualism” at record pace, as the dissonance Didion observed in 1990s LA continues to compound under a new antagonist: artificial intelligence. As a result, we’re relying more heavily than ever on the same flawed principles to explain what will happen if the corporations that once sustained a middle class no longer have any use for it. In other words, AI appears to be stretching the narrative limits of our most treasured story beyond the point of coherence.

The US economy in its present state presents a dynamic contradiction. There’s never been a greater “divergence between equity returns and job openings,” a conflict that Derek Thompson resolved by splitting the baby into separate realities: “a booming AI economy and a lackluster everything-else economy.” To put a finer point on it: JP Morgan estimated that AI-related stocks have driven 75% of all S&P 500 growth since 2022, which might be why Ruchir Sharma wrote for the Financial Times that, at this point, the story of American optimism is indistinguishable from three Nvidia chips in a trenchcoat. A portfolio manager told the Wall Street Journal that “‘[i]nvesting in US markets is almost becoming a one-way concentrated bet on the development and proliferation of AI,’” a statement prompting me to perform a nervous asset allocation check which revealed the metastasized US exposure in my portfolio. (It should be noted that, for all the talk of US stock market impenetrability this year, international stocks have outperformed the US by the widest margin since 2009.) The closer your proximity to this “booming AI economy,” the better you’ve done. Still, watching your wealth grow from artificial intelligence at the same moment your job security is threatened by it is a little like using the right hand to repair what the left is actively destroying.

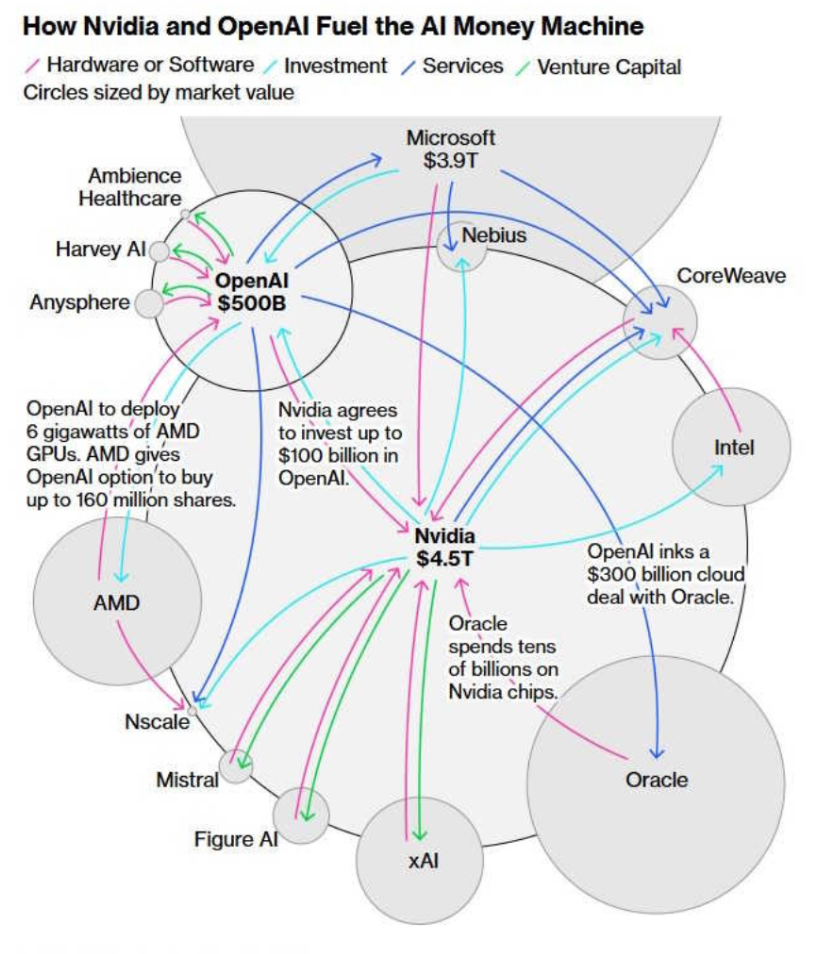

Booming or not, the fundamentals of this gold rush leave something to be desired. OpenAI is, according to the magic of the market, “worth” $500 billion, despite its mere $12 billion in revenue. Nvidia, a company that makes chips, is somehow worth more than the entire pharmaceutical industry combined. A recent Bloomberg visualization of these companies’ financial interdependencies, which would appear to show a rat king of incestuous funding, offers little in the way of clarity about the true source of the demand or value:

The dominant story now is that the US economy is a complex puzzle that needs to be unlocked, and the alchemizing power of artificial intelligence will either forge a skeleton key that slides effortlessly into our most inscrutable problems, or it will destroy us all, or it will continue to be a useful if functionally limited chat partner for lonely young men and people weaning themselves off WebMD with large language model-powered symptom radar. Only time will tell, or so the story goes.

A clearer picture emerges when we confront the uncomfortable reality that these disparate conditions could, under our current configuration, coexist indefinitely. For bulls, the logic goes something like this: “The main reason AI is regarded as a magic fix for so many different threats is that it is expected to deliver a significant boost to productivity growth, especially in the US. … Higher output per worker would lower the burden of debt by boosting GDP. It would reduce demand for labor, immigrant or domestic. And it would ease inflation risks, including the threat from tariffs, by enabling companies to raise wages without raising prices.” The magical thinking of this “best-case scenario” is revealing, because it relies on a tacit acceptance of the rusting, decades-old infrastructure of Reaganomics. This blind faith in “productivity gains” as the cure-all, no other shifts required, represents how profoundly narrow our understanding of national flourishing has become. AI exuberance, then, belies a faith in the soothing myth that we can outrun a core rot exactly as quickly as we can make GDP go up. No matter how obvious it becomes that this hasn’t been the case for at least 30 years, Didion’s ethos rings true here: Soothing myths can be hard to part with, particularly if the majority of your resources depend on you (and everyone else) continuing to believe them.

When spelled out so plainly, it becomes clear who, exactly, the “economy” in this accounting chiefly exists to serve: a set of people who, like Southern Pacific in California 150 years ago, have effectively expropriated and monopolized the resources of the US through a neat understanding of tax law and pay-to-play politicking. Didion’s observations about Southern California’s economic downswing feel eerily prescient:

This “new economy” was to be built on “international trade,” an entirely theoretical replacement for the gold-standard money tree, the federal government, that had created these communities. Many seminars on “global logistics” were held. Many warehouses were built. The first stage of [construction] was near completion before people started wondering what exactly these warehouses were to bring them; started wondering, for example, whether eight-dollars-an-hour forklift operators, hired in the interests of a “flexible” work force only on those days when the warehouse was receiving or dispatching freight, could ever become the “good citizens” of whom Mark Taper had spoken in 1969, the “enthusiastic owners of property,” the “owners of a piece of their country—a stake in the land.”

Here, she’s providing an answer to the question she posed earlier: What happens when an artificially created ownership class stops being useful? Put another way: What happens when a robot can do your job nearly as well as you can?

Technologically, the world-changing potential of artificial intelligence—while “entirely theoretical” right now—may be something genuinely novel. But economically, the more I read about the grandest flavor of conjecture, the more familiar its implications feel. No matter how valuable it becomes, it will leave our foundation, plagued with persistent and neglected cracks, untouched. A true repair would require a more wholesale rejection of the American delusions we take most for granted, like the sanctity of meritocracy’s equalizing powers, wealth concentration as the most reliable indicator of brilliance (that will eventually, it goes without saying, trickle down), and perhaps most of all, the myth of total self-sufficiency that Didion interrogated so soberly in Where I Was From.

The good news is that our current model of publicly traded (and publicly owned) companies is, in some respects, actually quite elegant. You’d be hard-pressed to find a better mechanism for diversifying and distributing the spoils and risks of a complex, profoundly interrelated economic system. Chopping up ownership of every corporation into tiny, tradable shares that can be bundled together and distributed via a product like an index fund is (Wall Street Journal subscribers, cover your ears) borderline socialist in its mechanics. We’re all familiar with why and how this ends up falling short in our current iteration, but it can be summed up in two words, both of which apply to AI valuations: concentration and manipulation.

Roughly 87% of those shares belong to 10% of people, per a Ritholtz analysis from February, which is partially why consumer spending still looks so strong (the top 10% are spending almost as much as the bottom 90% combined), and short-term thinking is the name of the game in an era of stock buybacks and equity-based executive compensation packages. But an infrastructure already exists for something far more prosperous; something that distributes the value of this economy more evenly to the people who are laboring every day to produce it. The gamble on world-changing tech just makes Didion’s project of abandoning our “self-soothing delusions” feel all the more urgent—because if what the bulls say is true, our leverage as human workers to determine our fate will never again be greater than it is right now.

October 27, 2025

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time