Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

I woke up Saturday morning eager to clean my apartment.

My excitement surprised me. Six months earlier, I had resigned myself to the idea that a smaller space meant cleaning professionals were no longer necessary (yet another cost-efficient benefit of downsizing), the way you might resign yourself to getting up early for the gym or eating leftovers. But lately, slowly and methodically cleaning the apartment has become something of a weekend ritual; a dedicated morning hour for gliding from one physical task to the next, each producing its own satisfying, visible progress in the form of unrumpled clean sheets or a sink free of dried toothpaste.

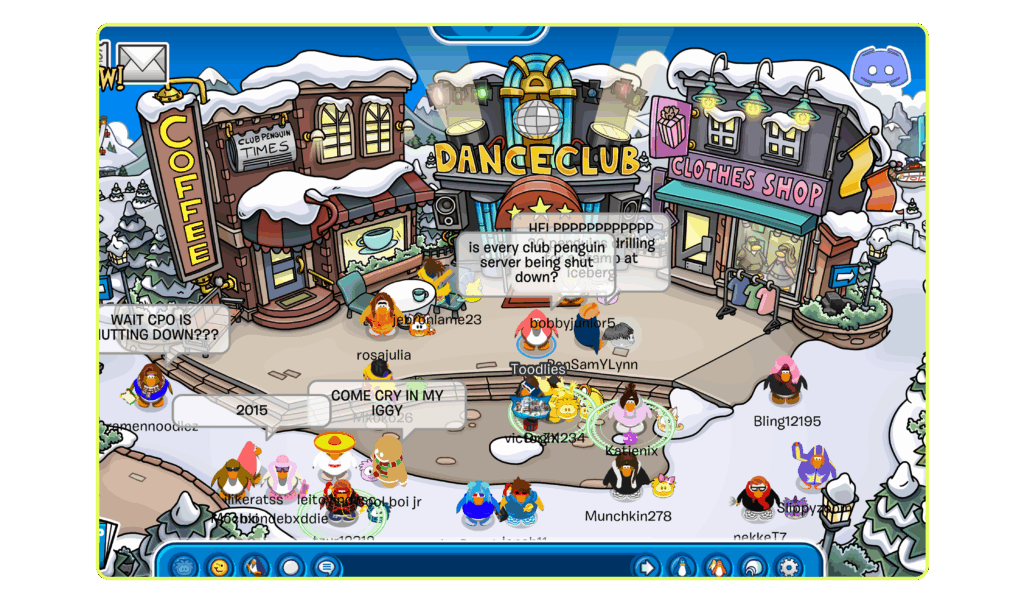

In most other areas of my life, my effort and conscious attention exist in abstract spaces no more real than the Town Center of Club Penguin—the cells of a spreadsheet where my resources are carefully transcribed and monitored, the orchestra of 0s and 1s inside my phone composing a song for my engagement patterns, the cacophony between my ears that I translate into colorful blocks like hard candies in a Google Calendar. The truer this becomes, the more I gravitate to the fleshly thrill of tasks that generate immediate tangible evidence of their completion.

Just another day in the office.

Sometimes when the idea of cleaning presents itself as an unlikely respite, I think about something I learned a few years ago about the fundamental human desire to “act upon the world.” This begins in infancy, when the new human learns that their actions create physical feedback: When I kick my foot, this toy moves, or, When I cry, my caregiver reacts to me. In that respect, our sense of agency is learned and sustained through our bodies, not abstract reasoning. And bodies, as most of us have learned the hard way, have a way of not just experiencing physical reality, but enforcing it.

Spending too much time in the ether of the abstract sometimes has the unintended effect of fooling the agent into believing that the physical is as easily controllable as the digital. It’s interesting to observe the mind try to bridge this gap. Late last week, my mom told me that my 95-year-old great uncle had been struggling with some strange symptoms and, within a matter of days, had been moved into hospice. When the health of someone in their nineties begins failing, it feels wrong to describe this deterioration as “sudden,” as failing is what all bodies do eventually, particularly those fortunate enough to approach their centennial. Still, when I finally saw the text preview appear in my messages that he had passed away, I left the text unread for hours, the information theoretically suspended beside a bright blue dot. Maybe if I didn’t open this message, the reasoning went, I could delay the physical reality of its contents, holding it instead in this liminal space where data, unlike bodies, can live forever.

Another example: Scrolling Instagram the other day, I caught a Story update from a woman who was a close friend in college. We sported nearly the same name—Katie G.—and our relationship was the site for some of my more responsible choices, like drinking enough water and exercising every morning. Where my other friends applied the storied “work hard, play hard” mentality (the former to their medical or law school applications, the latter to their alcohol consumption), Other Katie G. clocked a 10 PM bedtime on Friday nights and spoke often about her desire to have a family of her own.

The update was that she was beginning the first of 12 rounds of chemotherapy on her daughter’s first birthday. I stared at the word “chemo,” finding it totally illegible next to the news of her child turning one, a glitch. How, I wondered, could Other Katie G. have cancer? Her profile offered no other evidence of her diagnosis—which, bizarrely, comforted me, as if this made it less real—just pictures of the doughy biscuit of a baby she wanted so badly.

It was Other Katie G. I thought about when I read this weekend’s viral New Yorker essay written by Tatiana Schlossberg, Caroline Kennedy’s daughter and JFK’s granddaughter, about being diagnosed with terminal leukemia at 34 in the days following the birth of her second child. Much like I just did with emphasizing Other Katie’s healthy choices—as if to say, This is all some horrible mistake; she completed all her to-do lists and responded to all her emails; you don’t understand, she woke up early on weekends and cleaned her apartment—Schlossberg likewise emphasizes her apparent health in the months leading up to her diagnosis, how she could run and swim and ski for miles. The article gave me the intense desire to close the tab, to remove this possibility from my own body by way of removing it from my screen, to not allow myself to imagine even for a moment how such a revelation would, instantly, transform my priorities and stressors to dust, and what that might say about my priorities and stressors.

As someone on the Millennial–Gen Z cusp, I read a lot about my cohort in the news—that we, in a break from thousands of generations that preceded us, want special and unique things like flexible work and houses and socialism and—who can forget this one—“experiences.” But the millennials I read about online bear very little resemblance to the young people I meet in the physical realm, who all seem to want more or less the same thing: to act upon the world, and preferably in a way that matters. Recently, Gen Z economics wunderkind Kyla Scanlon visited nine cities as part of an In This Economy? road show and pointed out in her post-game analysis that a surprising number of AI-related conversations with experts revolved less around reskilling or upskilling than purpose and meaning and, I assume, how to find those things in a world with—hypothetically, eventually, theoretically—very little abstract knowledge work. “The students were amazing,” Scanlon writes of her visit to a Florida college. “Their questions were practical: How do we afford housing? How do we navigate AI? How do we find meaning in work that might not exist in 10 years?”

My generation is particularly susceptible to the siren song of “affordability politics,” this news coverage notes, because they feel they cannot afford the lives they imagined for themselves, which is another way of saying they cannot access the things they need to act on the world in the ways they want to. The Wall Street Journal, for example, published a piece about Trump and Mamdani’s unexpectedly warm Oval Office meeting, pointing out the obvious: Both of these very different, very popular politicians campaigned on the cost of living, this thing that the proles won’t stop whining about. The article declares that the so-called affordability crisis is, among other things, not real, and even if it were real, it would not be a problem that’s solvable. (Beside the story, another piece asked a question which was, evidently, deemed solvable: “Is $200 Million the New $100 Million in Luxury Real Estate?”)

This is why you don’t let billionaires run media companies.

Young people, like all people, seek meaning in different ways (starting or not starting a family, pursuing one career or vocation over another, developing an arsenal of hobbies) and many even seem to face similar challenges (an absence of time that someone else has not already bought and paid for, resource scarcity, self-esteem battered by the beauty or masculinity industrial complexes), but I am always struck by the uniformity in the texture of their desires. An “affordability crisis” is merely the name we’ve given to the phenomenon where people feel blocked, through some economic force real or perceived, from pursuing that which gives their lives meaning. (The opposite phenomenon, an extreme nihilism that’s certain everything is meaningless and looks to violently enforce that view on others, received a lot of attention earlier this fall when “groypers” were caught in the discourse’s high beams, squinting and unprepared.)

The sensory experience of the affordability crisis is the frustration of action stifled before it has a chance to produce its desired consequence—when studying and graduating means loans but no disposable income, when a job means a paycheck but no career advancement, when saving means sacrifice but no promise of reward, when the decision to grow a family means not just profound responsibility but unrelenting financial pressure. An economy where you kick your leg but the toy does not move or you cry and the caregiver does not react. The affordability crisis is better understood as an agency crisis, and that’s as real as you or me. The moments, then, when something responds (the sink shines, the baby cries for the first time, the job offer comes through, the body heals) can feel like life itself is answering back—however briefly—that yes, you’re still here.

November 25, 2025

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time