Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

I spent a few days last week in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to deliver a keynote called “Your Money, Our System: Collective Tools to Move the Needle” at an annual women’s conference. When I agreed to the presentation, I hadn’t realized that Teton County held the title of ‘greatest income disparity in the United States,’ a sad statistic that was recounted to me roughly every eight hours by a different smiling, wide-eyed resident. It is, to date, the most American place I have ever been—less for the way it embodies our ideals than for how it exposes them so plainly.

The top 1% in Teton County earns 142.2x more than the bottom 99%, compared to the US’s overall differential of 26.3x. The average annual income of that top 1%? Hold onto your Stetson: $22,508,018. (In the Economic Policy Institute’s accounting, New York, New York comes in at #2, with a modest-by-comparison one-percenter income of $8,983,154.) These numbers are from 2015, preceding the pandemic-fueled billionaire infestation, so it’s likely more disparate now. Jackson is an “onshore offshore tax haven,” according to a jauntily scored Bloomberg video, referencing Wyoming’s 0% state income tax, 0% corporate income tax, 4% sales tax rate, and 0.55% effective property tax rate, one of the lowest in the country. (Wyoming ranks first in the Tax Foundation’s euphemistically named “2026 State Tax Competitiveness Index.”)

Tax breaks aside, the attraction is obvious. Sometimes you go places where it’s hard to imagine how anyone ever got brave or deluded enough to attempt paving the first road or building the first home there, given the landscape. But Jackson, hemmed in on all sides by what I can only describe as patented Purple Mountain Majesty, makes it clear why you’d try. There’s a rugged romance to this town that it still embraces: A sign on Highway 22 welcoming visitors (and workers who cannot afford to live within town limits) from Idaho over the Teton Pass announces its mythos as “THE LAST OF THE OLD WEST.” (This perilous commute was disrupted for three weeks last June when the infrastructure failed and the road literally slid off the side of the mountain.) A fictionalized version of Jackson even appears in HBO’s Emmy Award-winning series The Last of Us, portrayed as singular in its ability to survive a zombie apocalypse as a relatively thriving, walled-off settlement, a testament to the American fantasy of self-sufficiency against even the ugliest of odds.

Post-apocalypse American Western Utopia, per HBO.

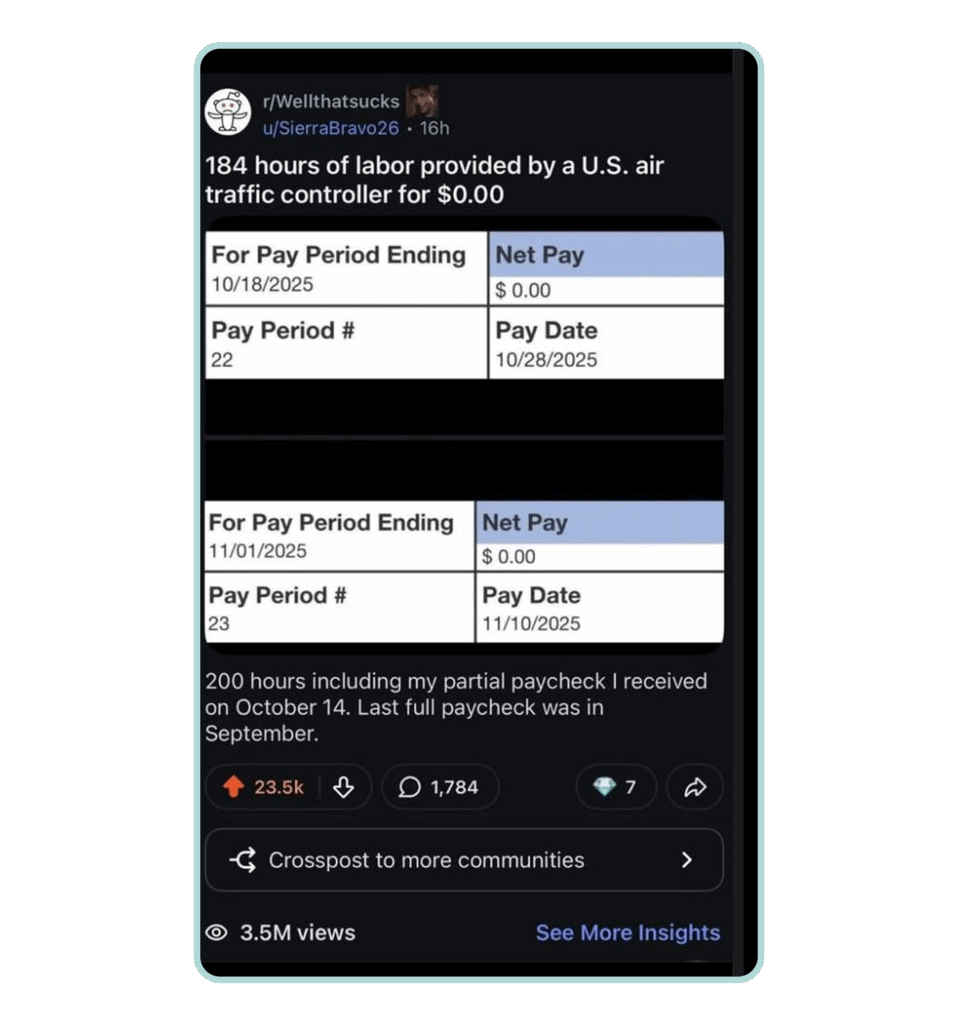

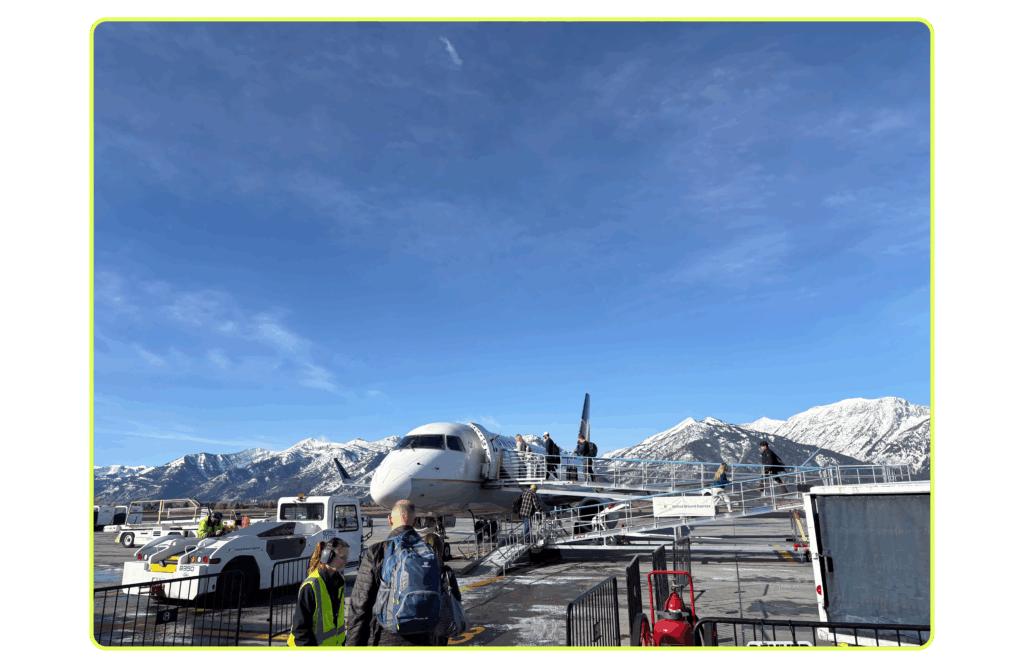

Flying into the valley “can be brutal,” a friend warned me, because of the quick descent over the Tetons. Already a slightly nervous flyer, I stalked the r/ATC subreddit before my trip. Normally, it’s a digital watering hole where air traffic controllers congregate to discuss niche industry drama with specialized terminology I don’t recognize. But since the government shutdown began last month, the subreddit has been overrun with posts about working without pay and questions from other voyeuristic nervous flyers asking if the stress of working unpaid six-day weeks or picking up second jobs is going to make the public less safe. The response was—horrifyingly—mixed.

Bewildered Europeans occasionally comment to express pity (“In Germany,” one wrote, “it is illegal for the government to make people work without pay.”). When well-meaning outsiders urge them to refuse to work, a reliably beleaguered flood of comments reminds OP that, unlike being forced to work without pay, striking is illegal for federal workers. Once inside the terminal at JAC, I noticed a conspicuous absence of other commercial planes taking off down its single runway—only Cessnas and Gulfstreams and other tiny jets with presumably private owners.

The strange thing about the wealth disparity in Jackson, with its population just shy of 11,000 people sharing less than three square miles, is how unusually proximate it feels. I’ve never met so many regular people with close, personal connections to billionaires. I spent time with a ski instructor who works for the resort, paid somewhere in the neighborhood of $19 per hour. (I struck up a conversation by asking her about “dropping Corbet’s,” referring to a notoriously harrowing run called Corbet’s Couloir which begins with a near-90-degree vertical dropoff that Colorado transplants like me learn to discuss with reverence in the company of people who don’t do things like, for example, read r/ATC before flying.) She was in her early forties, with wild, curly blond hair that called to mind 2007 Taylor Swift, and it became quickly apparent that she was a favorite of the Jackson vacation-home class. She ticked through a few locations she’d traveled to with clients—Egypt, Alaska, the Maldives—sometimes for ski instruction, other times, I gathered, as a comped tag-along on their six-figure vacations, simply because she’s a great hang. (Can confirm.)

After the conference ended the second night, a group of us got dinner together at a restaurant that paired things like elk hash with $17 cocktails. After a story about how she had grown accustomed to tracking one client’s jet on FlightAware whenever the family was running late for their lesson, she told me she was about to lose her health insurance. “I’m on an ACA plan,” she said, by way of explanation. With the planned upcoming expiration of Affordable Care Act enhanced subsidies, an average premium hike of 114% will price some portion of the 24 million Americans enrolled in ACA plans out of healthcare.

For some, premiums will rise a lot more. That morning, I made an unlikely connection with the event photographer. He looked like the type of man I expected to see on the Denver season of Love Is Blind: shoulder-length brown hair, a flannel shirt, a flat-brimmed hat bearing the logo of a local brewery. He beelined for the book signing table in the theater lobby after my presentation ended, where I had decamped to decompress from an unusually tense question-and-answer session. “When I heard your voice, I realized I know you,” he said, pulling out his phone to show me texts with his sister about my podcast, Diabolical Lies.

Relieved to be in the presence of someone who voluntarily listens to my voice for entertainment, we settled into an easy rapport. “It’s important for someone to come into this town and say the things you just said,” he told me, “but it also takes courage, because some of the people in that room do not want to hear it.” (Being told my talk was courageous had the same effect on the pit in my stomach as being commended as “brave” for wearing a bathing suit; which is to say, I was unaware my words would be controversial.) He told me he’s self-employed, and volunteered that his ACA premium is about to go from $150 per month to more than $780. I got the impression he wasn’t sure what he was going to do yet.

The ACA subsidies, which make insurance more affordable for 92% of enrollees, mostly act like a funnel for draining public funding into the private profits of the insurance companies. Still, the practical effect of removing them without offering an alternate public option means people lose their health insurance, or spend a mortgage-sized amount to retain coverage. My presentation covered issues like this one, how the privatization of public goods and services leads to market-distorting wealth that makes life more expensive for everyone else; issues that most people in Teton County probably didn’t need to learn about via Google Slides because they live them at the end of every month when the rent comes due.

But not everyone in the audience found it resonant. One woman, a fast-talking New Yorker who sought me out afterward, said she found all my material about the dream of universal basic services and union density insulting; she insisted the answer wasn’t “more government,” but more financial literacy. “Financial literacy is the answer,” she told me, “not all this socialism.” I told her I put all the financial literacy “in there,” punctuating the words by tapping on my book with a stiff forefinger. She waved her hand over the stack of signed copies, as if exiling a bad smell. “People don’t learn from reading,” she insisted (news to me), “they learn by doing.” Fair enough; no further word on what she’d like them to do.

While in Jackson, I had the distinct feeling of accidentally being at the center of something, like an ant who had marched across the frontier (via SkyWest doing business as United Airlines) and mistakenly wandered under a magnifying glass where all of America’s glory and failure had been concentrated into a single, unforgiving beam. For all the talk of its economic uniqueness, Jackson seemed to me less an anomalous expression of American capitalism than an exceptionally pure one. In the Jackson of The Last of Us, the town is “an oasis of communal living,” where residents “share the responsibilities of cooking, cleaning and maintaining the town” in “relative safety and comfort.” “The Jackson community has figured out what they need to survive their world’s fungal-themed zombie apocalypse,” Taylar Dawn Stagner writes for High Country News of the fictionalized rendition: “each other.” In real life, where the disease is different, things are a little more atomized, and solutions a little less pat. (Even the HBO version doesn’t end so tidily: The zombies do, eventually, breach the town’s defenses.)

After the final panel closed Friday afternoon, a young woman with raven hair approached the foot of the stage. “Your book…” she began, “Is it out there in the lobby?” I nodded. She told me she worked at the local bank in their private wealth division. “Do you like your job?” I asked, tentatively. She seemed reserved in a way that bordered on melancholy. “I do, most days,” she began, “but what you were saying up there…” she searched the ceiling for words. “I see that every day in my job. Some of my clients are amazing people; very philanthropic. Others made billions in another state and don’t want to pay taxes there, so they come here instead, and my job is to help shield that wealth. I hate that part.”

This sort of ambivalence was everywhere. Another woman, a former nanny for a person who resides cozily in the top 10 of every “richest people on earth” list, described a friendly yet intense working relationship, careful not to violate a non-disclosure agreement that I can only imagine was longer than the Jackson airport’s sole runway, but made clear her feelings were complicated. The core complication being: In Teton County, billionaires are not an abstraction, they’re your neighbors—people who, like the rest of us, are capable of wonderful and terrible things.

One such terrible thing: cowboy cosplay.

The market has priced a one-bedroom apartment in Jackson, Wyoming at an average of $3,193 per month. To live in such a space without your rent absorbing more than 30% of your monthly gross income (let the record reflect I prefer using net income), you’d need to earn $127,716 per year. At dinner after the conference, I asked one of the organizers what she felt the town’s biggest challenge was. “I mean, it’s the inequality,” she answered. A former city councilwoman sitting to my right, ever thoughtful and practical, interjected. “To be more specific,” she added, “it’s that the people who work in this town cannot afford to live here. Their wages are just not high enough.”

Silently, I wished the woman who had felt insulted by my presentation could’ve heard this exchange, and wondered how, exactly, she’d counsel those who had been run out of town to “financial literacy” their way into a $3,200 apartment and $780 catastrophic health insurance on $20 per hour. “To be clear, these aren’t all low-wage service employees who staff T-shirt shops or clean toilets in our county’s many, often vacant luxury mansions or pricey hotel rooms,” Brigid Mander reported about Jackson for Slate in 2024. “It includes teachers and nurses, sheriffs’ deputies and doctors, air traffic controllers, wildlife biologists, mountain guides, and other seemingly integral parts of a functioning community.” As is true in the rest of the United States, an increasing number of people who work in this economy cannot afford to live in it.

In the valley, every layer—all the beauty, myth, and material impossibility—felt stretched taut, as if pulled toward the event horizon of the American economy, threatening to collapse under an infinite blue sky. When we turned onto the road leading to the airport the following morning, the snow-capped Tetons loomed so imposingly in the distance that I was surprised to feel a cold stinging at the corners of my eyes, awe and grief in equal measure.

November 10, 2025

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time