4 Tax Implications of Being Partially Self-Employed that You Need to Know for 2021’s Tax Season

Disclaimer: I am not a tax advisor, and all information is solely intended to be educational in nature. Please consult a qualified tax professional.

I’m just going to warn you – this article is going to feel like a mathematical dumpster fire, so before you get freaked out, remember: Any good tax software could help perform this mental jujitsu for you.

I just like to know how things work, and I want to show you today how powerful self-employment retirement accounts can be for saving on your taxes.

If you’re a W2 employee, your tax situation is more or less decided for you (assuming you filled out your W-4 accurately).

(The IRS has a handy-dandy Tax Withholding Estimator to help you complete your W-4, but the tool becomes less useful as your situation becomes more complex.)

If you’re a W2 employee, Linda in HR cuts you a check every other week and assesses the amount you owe in taxes accordingly, and they come directly out of your paycheck. Aside from making pre-tax contributions to your employer-sponsored retirement plan (which you absolutely should, to the best of your ability) or your HSA, you… kinda owe what you owe.

For freelancers and the self-employed, not so much.

I’m in an interesting (fortunate) situation right now given my ongoing full-time W2 wages and self-employment income, and as a result, I’m learning quite a bit about #taxlaw on accident.

Since this is my first year with self-employment income and W2 wages, I’m skirting the quarterly tax situation because enough of my total tax liability is being paid through my W2 wages.

That’s a fancy way of saying Uncle Sam is bleeding me dry enough from my “real” jobs that he can’t actually come after me for quarterly taxes yet, based on my total income tax paid last year. I know. It’s a lot.

Self-employed tax implication #1: Avoiding quarterly taxes in year 1

For those of you in your first year of self-employment who are still working full-time, it’s likely you’ll generally be able to avoid the penalty for not filing quarterly as long as you’re still paying 100% of the amount you owed last year (or 110% if your income last year was more than $150,000).

For example, if I owed $20,000 last year and this year I’ll owe $25,000, as long as I pay the full $20,000 this year, I can avoid penalties in the short-term. In other words, as long as I pay at least the amount I owed last year throughout the current year, I’ll (probably) avoid penalties for underpayment.

It’s worth noting here that if I only had self-employment income and wasn’t paying any taxes on W2 wages, this would be a different story – the IRS will charge penalties (technically, they’re charging you interest to reflect the time value of the money you owed them).

This is because you have to pay tax as you earn – that tax is due throughout the year, not in April. (That’s why your employer withholds your taxes from your paycheck and sends it to the IRS for you.)

It’s also worth noting that I am not a tax expert, so consult a professional tax advisor if you need help figuring this stuff out for your own situation and don’t feel confident doing the research on your own. I know not everyone spends their free time on IRS.gov like I do.

So let’s call this for what it is: A little tax experiment. Fun, huh?

My issue with normal self-employment tax advice

Typically, the rule of thumb I hear thrown around is to set aside 30% of your self-employment revenue every month and let it sit in a savings account, waiting for the harsh blow of your quarterly tax bill to come crashing down in a guillotine-inspired reign of terror.

Let’s do an example, so you can see what I mean. I know self-employment income varies month to month, but let’s make this example easy and say you’re a self-employed person who’s making $10,000 per month (gross revenue).

Let’s pretend you have low overhead and your business expenses for the year were only $2,000.

And for the sake of this example, let’s say you also have a full-time job (like me!) that involves paying taxes on your W2 wages. Let’s say you make an $80,000 salary from that job.

Got it?

W2 wages: $80,000

Business income: $120,000

Business expenses: $2,000 (no employees)

If you set $3,000 of your self-employment income aside per month (30%), you’d eventually save around $36,000 over the course of the year (though after year 1 of self-employment, you’d be paying it in quarterly taxes to avoid underpayment).

Because remember, at this point, we’re just setting aside 30% of our revenue, assuming that’s what we’ll owe in taxes.

Your tax liability on $80,000 of W2 wages and $120,000 of self-employment income

Again, this example might feel ludicrous, but I have a growing network of friends that work full-time jobs and run side businesses – it’s less uncommon than you might think, even if it feels ridiculous given the numbers I’m using for the example (round numbers, baby).

This example really twisted my brain, and it made me realize a weird truth about calculating tax liability:

You basically have to think about your “FICA” tax (Social Security + Medicare) completely separately from your federal income tax, because the FICA taxes apply to more of your income.

When people talk about their “tax brackets,” they’re referring to federal income tax, but the way your FICA taxes are calculated works a little differently.

I used to think that federal tax stuff was hard to calculate, but that was before I was introduced to the hairy and obnoxious world of FICA tax. Strap in.

(If you’ve ever looked at your paycheck, you’d see “federal tax,” “Social Security tax,” and “Medicare tax” as separate line items draining your net pay.)

I’m going to do this by hand (using the tax forms and Excel; not on paper, you pilgrim) to avoid the total black box nature of tax calculators.

Don’t worry, I’ll show my work. For simplicity, let’s use one of the wonderful 50 nifty states that doesn’t have state income tax. That means we’re just looking at federal and FICA taxes.

So the first funky thing to consider with partial self-employment is that you’re now liable for the self-employment tax.

Self-employed tax implication #2: The 15.3% self-employment tax, and how you may end up legally avoiding some of it

That “30% rule of thumb” comes from the fact that self-employment income is taxed at an additional 15.3% to make sure that self-employed people still pay Medicare and Social Security tax.

If you’re like, “Where the hell did 15.3% come from?”, you may notice that it’s double the “FICA” line item on your paystub of 7.65%. W2 employers are responsible for paying their half of the FICA taxes. When you’re self-employed, you’re the employer and the employee, henny – that means you’re on the hook for the whole 15.3%.

Economically speaking, it’s likely you’re offered a salary that’s 7.65% lower because your employer knows they’ll have to cover their half of FICA.

Because the IRS loves to make things complicated, it’s not as simple as multiplying your net revenue by 15.3%. That would be too easy. The actual calculation is like this:

Gross revenue – business expenses = net revenue

($120,000 – $2,000 = $118,000)

Net revenue * 92.35% = The amount of business income on which you pay self-employment tax

($118,000 * 92.35% = $108,973)

Why?

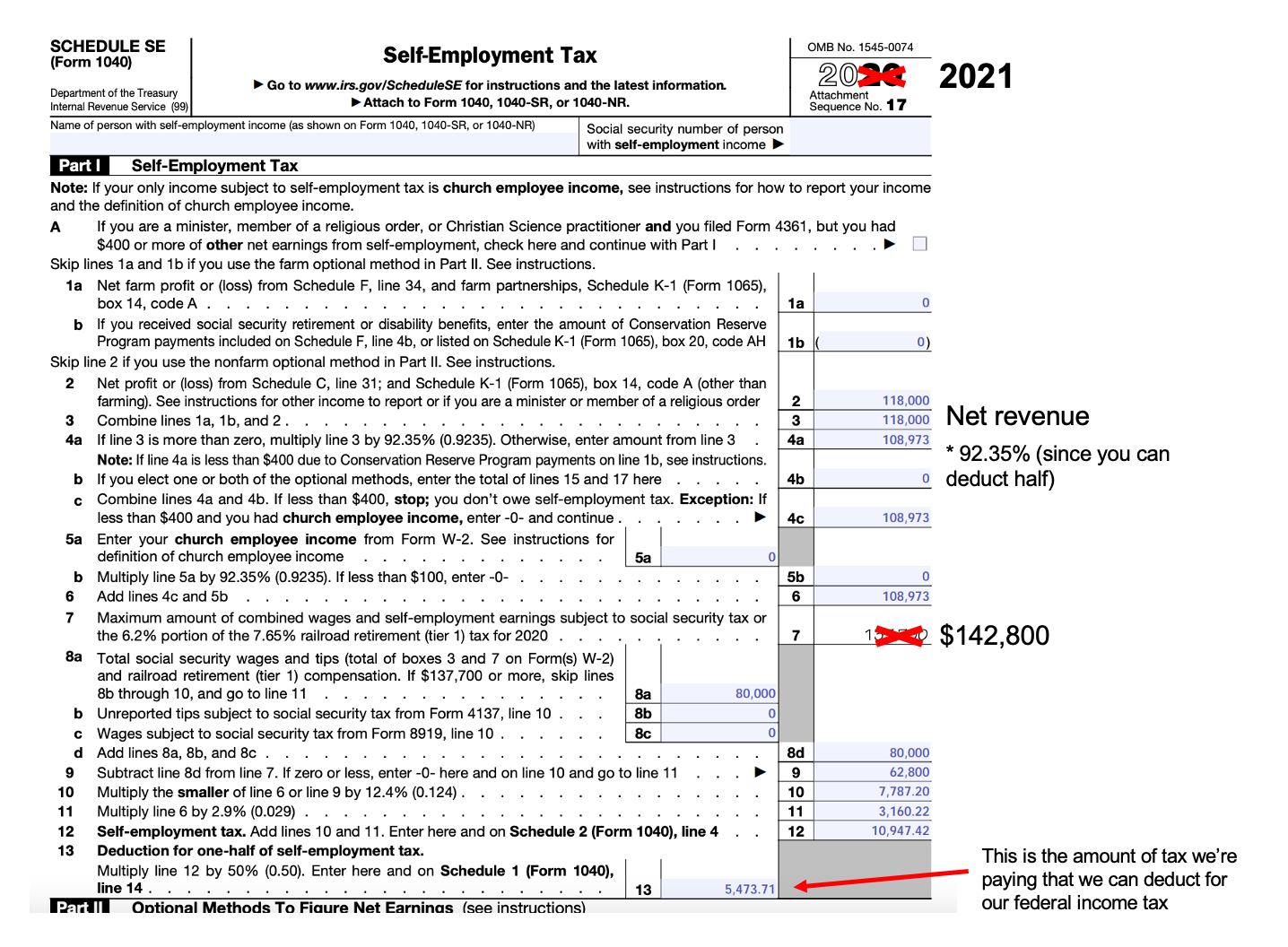

Because the very fact that you can deduct half your self-employment tax impacts the taxable self-employment income itself. This honestly made my head hurt, so here’s the tax form (Schedule SE – Self-Employment Tax) to explain:

Since this form was for 2020, the wage limit was $137,700; in 2021, the upper limit is $142,800. This is one of the few taxes that you actually pay less of as you make more money.

Notice how I added the $80,000 of W2 income in, too, since her total income is over that $142,800 Social Security limit.

So Social Security has a nifty income limit – Medicare doesn’t. You’ll pay 2.9% on all of your self-employment income, regardless of your W2 job.

To figure out how much you owe, the IRS basically looks at the difference between the W2 wages that have already been taxed for FICA ($80,000) and that $142,800 Social Security upper limit, and charges for Social Security on the self-employment income that falls in that space between ($62,800).

Medicare tax is charged on the entire amount ($108,973).

Our hypothetical friend’s self-employment tax deduction is $5,473.71, per the form. That’s considered her “employer” portion of Social Security and Medicare.

That $5,473.71 is important, because it tells us what can be deducted when we calculate our federal tax liability.

Another benefit of self-employment income is that you probably qualify for a pretty dope 20% deduction (lowering your taxable income) called the Qualified Business Income deduction.

Self-employed tax implication #3: Qualified Business Income deductions

Most small business owners who have less than $164,900 (single) or $329,800 (married filing jointly) of taxable income qualify for a straight 20% deduction of their net business income. (Note that certain business types are subject to special rules.)

Qualified Business Income is the amount of income after you subtract all your expenses and deductions, including any contributions to pre-tax retirement accounts like the SEP IRA or Solo 401(k) – but more on that later.

For example, our friend in this example made $120,000 of self-employment income. She spent $2,000 in business expenses throughout the year, and is going to deduct the part of her self-employment tax that she’s legally allowed to ($5,473.71).

That’s the amount of self-employment income that she’d owe taxes on, if she doesn’t do anything else to lower her taxable income.

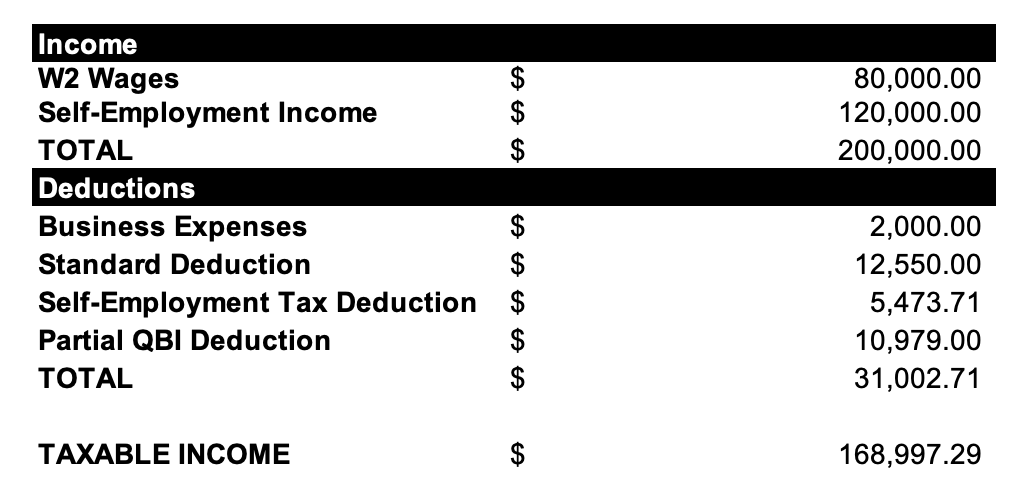

And while her total gross income is $200,000 between jobs, after taking the standard deduction for singles ($12,550), deducting her business expenses ($2,000), and deducting half her self-employment tax ($5,473.71), her total taxable income is down to $179,976.29.

Pause!

If you were paying attention, you may have recalled one small issue:

The beginning of the phaseout for “singles” QBI deductions is a taxable income of $164,900.

Remember? There’s an income limit, and technically, she’s over it, but not by much. She would only qualify for a partial QBI deduction of $10,979.

If only there were a way for us to deduct another $7,025 in QBI… (Hold that thought!)

We definitely want to earn the full QBI deduction if we can, because it means we can wipe the full 20% of our net business income off our federal tax bill. Let’s see what we can do.

Calculating her tax bill

Something to note:

To calculate federal income tax, I basically flowed all $200,000 of income ($80,000 of W2 and $120,000 of 1099) through the U.S.’s progressive tax system to determine how much of her income falls in each tax bracket, then subtracted her deductions (standard deduction for singles, business expenses, and ½ self-employment tax deduction).

FICA (Social Security + Medicare)

We already know how much she owes on her self-employment income, because we used Schedule SE to calculate it: $10,947.42. That’s a decently big chunk, considering she’ll need to have the money ready at tax time to pay the bill.

Her W2 wages already had FICA taken out, so we’re good there.

Now, the real question mark is federal taxes – we know federal taxes were taken out of her W2 wages, but what does she owe on her self-employment income?

Federal Taxes

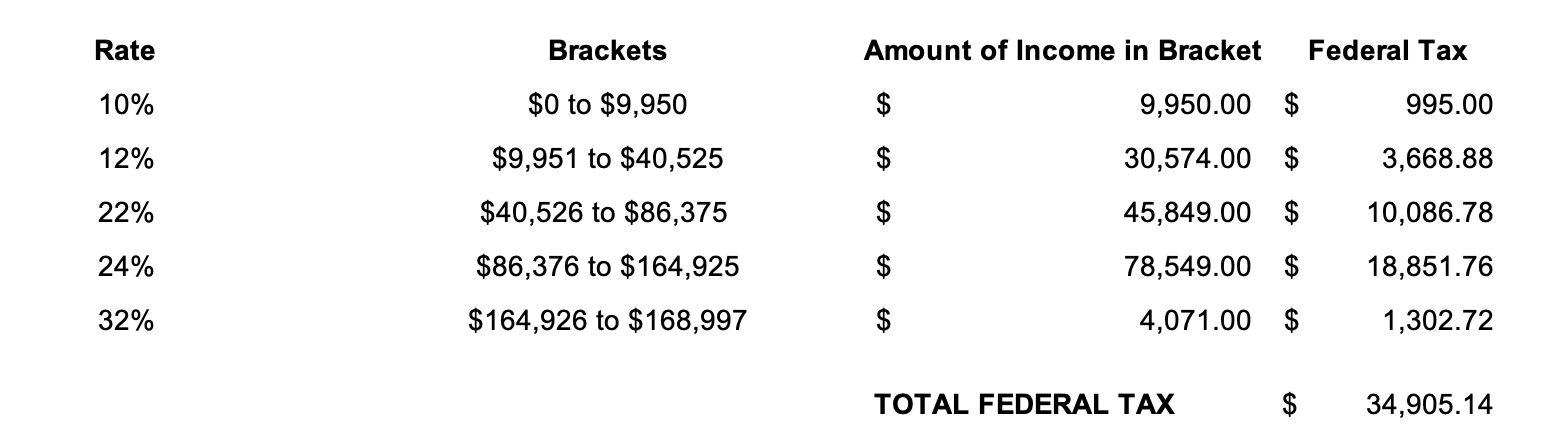

The U.S. uses a progressive tax system, which means you pay no federal income tax on your first $12,550 of income (known as the “standard deduction,” and hella handy for avoiding tax on Roth conversions later in life), and then you pay an increasing amount of tax on each bracket of income.

You can just wipe the $12,550 off the top, which is what I prefer to do.

So first, let’s calculate her total federal tax liability:

Our friend can deduct the standard deduction, $5,473.71 (half of her self-employment taxes owed), $2,000 for her hypothetical business expenses, and $10,979 for her partial QBI deduction, which means her total taxable income that flows through the federal tax system is $168,997.

Key takeaway: By sorting out her deductions and self-employment tax first, we can figure out how much money should actually be considered for federal income tax.

Sure, she’s earning $200,000, but she’s not paying federal taxes on all of it. Observe:

She owes a whopping $34,905 in total federal tax, in addition to the $10,947 in self-employment taxes.

BARF! Ugh.

Fortunately, some of that federal tax liability would already be paid through her W2 wages – approximately $13,389.66 would’ve come out of her paychecks already, assuming she didn’t tell her employer (via W-4 form) that she had other income (in other words, what most people do).

That means her tax bill is likely to be $34,905 (total federal tax liability) less $13,389.66 (W2 federal tax paid) plus $10,947 in self-employment tax:

$32,462

$32,462 due in one fell swoop at filing?

Yuck. Feels like we need to find a few other ways around this, huh? *cracks knuckles*

How to lower your tax bill

So before we start talking about how to manage that, let’s see if there’s a way we can pay less in taxes.

Huh? Pay less?

You bet, you high earner, you!

Let’s contribute to some pre-tax accounts

As someone with an employer-sponsored retirement account (like a 401(k), for example) and self-employment income, you would have access to a few incredible pre-tax retirement accounts:

The 401(k) and the SEP IRA.

Self-employed tax implication #4: Contributing to special pre-tax accounts for the self-employed

The SEP IRA is a gift to the self-employed. (There’s also a Solo 401(k), but since SEP IRAs are easier to open, we’re going to focus there today. Here’s an article about both of them.)

You probably already know that you can contribute $19,500 of your W2 income to your 401(k) and defer taxes.

You can also contribute 20% of your net self-employment income to a SEP IRA, up to $58,000 per year. Read it again. Up to $58,000 of additional tax-deferred income!

So let’s take full advantage of these magic tax school buses to lower that $32,462 tax bill!

Here’s how it can change the picture:

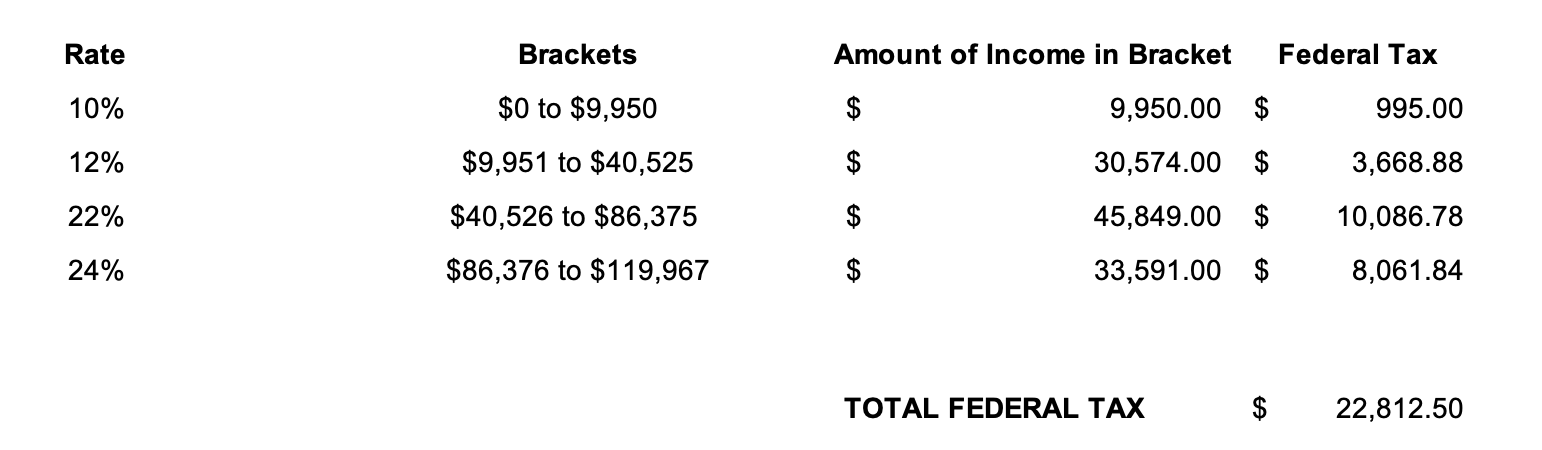

401(k)

She’ll put $19,500 into her employer-sponsored 401(k), knocking that much taxable income off her highest federal tax bracket. Easy peasy, since it’s a set amount regardless of your income.

SEP IRA

When we calculate how much we can contribute to the SEP IRA, we have to calculate 20% of her net pay.

And remember how (before) we qualified for the partial QBI deduction? After making that 401(k) contribution, we’re down below the income limit for the full QBI deduction. Yeehaw!

We just need to recalculate the QBI deduction after we decide how much we’re going to contribute to the SEP IRA, because you can’t deduct the same income twice. Weird, I know.

That looks like this:

$120,000 (revenue) – $2,000 (expenses) – $5,474 (half self-employment tax) = $112,526.

$112,526 * 20% = Total SEP IRA contribution of $22,505

Our new self-employment income is $90,021.

That’s the number we have to use to determine how much we can claim for a 20% QBI deduction: 20% of $90,021:

Our new QBI deduction is $18,004 (up from $10,979) thanks to our fat SEP IRA contribution.

What. A. Baller.

She can put $22,505 into a SEP IRA and defer the income and take her 20% QBI deduction, getting her final taxable self-employment income down to $72,017.

That means sis earned $120,000 in revenue and will only pay federal income tax on $72,017, all thanks to maximizing deductions and contributing the maximum to pre-tax accounts. As a reminder, the SEP contribution and the QBI deduction have no impact on FICA taxes paid.

$72,017 (taxable self-employment income out of $120,000)

+ $60,500 (taxable W2 wages after 401(k) contribution out of $80,000)

– $12,550 (standard deduction)

= $119,967

Let’s flow it through, friends.

Total deductions from pre-tax account contributions

Would you look at that? Now sister only owes $22,813 in federal taxes, as opposed to $34,905 – all because she contributed to a few fancy investment accounts.

Can I get a high five?

$22,813 – $13,389 already paid through W2 wages = $9,424 in federal tax liability, plus the $10,947 in self-employment tax.

Total tax bill = $20,371

$20,371 total tax bill, down from $32,463.

Leveraging those glorious pre-tax accounts means more money stays in our pockets. Hell yeah, sister!

We practically cut that sh** in half.

Remember how our original plan was to set aside $3,000 per month, for a total of $36,000?

That’s about $16,000 too much.

And obviously it’s better to have too much (and not too little) ready to rock to pay your taxes…

But the opportunity cost of an extra $16,000 saved isn’t ideal. If you assume a 7% return this year, that’s a foregone gain of $1,120.

And again – while that may not seem like much for a high roller like you raking in $200,000 per year, if you’re self-employed for a decade, that’s the compounding power of $1,120 of returns per year, compounding.

(Because we all know that if you’ve got an extra $16,000 after paying your taxes, you’re probably more likely to feel like it’s a ready-to-spend windfall and not just your actual money – a behavior we observe a lot with people who get fat tax refunds and spend them on crazy shit.)

The opportunity cost of $16,000 that could’ve been invested every year is high.

Assuming the same situation for 10 years, that’s a lost $228,068 if you assume an average annual 7% return.

It pays to know what you’ll owe, and invest the rest.

You can open a SEP IRA today in minutes with a robo-advisor – for a quick and dirty calculation of how much you can contribute of your overall business income this year, take your business income less expenses and multiply by 18%. For a more accurate calculation, you can always use the IRS SEP contribution worksheet.

The cool thing about the SEP IRA is that you have until the tax filing deadline (including extensions) to contribute for the previous tax year.