How to Determine if You’re on Track for Your Age

August 4, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

About six months ago, I wrote a post titled “How to Determine if You’re Behind.”

To save you the trouble in case you’re short on time, the moral of the story was this: To know if you’re “behind” financially, you have to know where you’re trying to go. Someone with $1 million who needs $2 million to retire and wants to retire next year is, by definition, behind.

Someone who has $50,000 to their name but doesn’t want to retire for 40 more years likely isn’t “behind,” despite having $950,000 less than the person with $1 million.

The point? We’re all trucking toward different finish lines, to some degree, so there is no singular benchmark against which we can measure ourselves.

That said, I started to wonder if there’s a sort of benchmark we could use that would tell us how we’re doing—surely there’s got to be some sort of equation or rule of thumb we can use, right?

When I started working, my dad told me you should have your salary saved by the time you turn 30 (meaning, if you make $50,000 per year, by age 30, you should have $50,000 saved).

I’m not sure where that advice came from, but I think I figured out how someone landed on it:

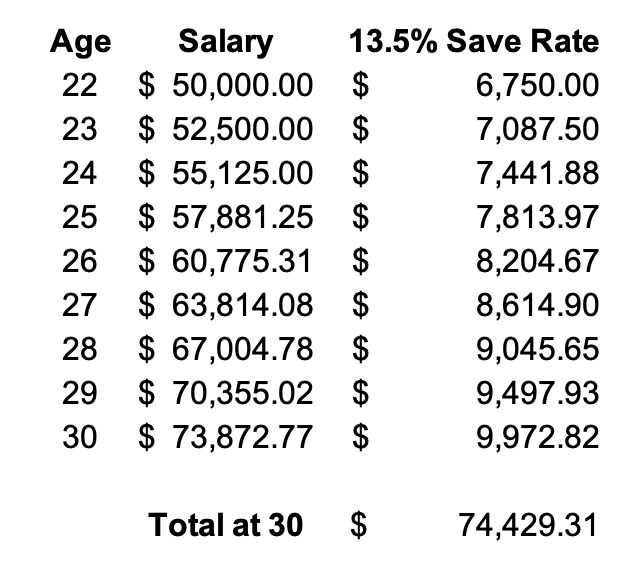

Someone who makes $50,000 per year after taxes in their first job at 22 would have 8 years to reach 30. Assuming they earn an average of a 5% raise every year, their salary range would look like this:

22: $50,000

23: $52,500

24: $55,125

25: $57,881

26: $60,775

27: $63,813

28: $67,003

29: $70,353

30: $73,870

One point of clarification that jumped out at me immediately? It’s unlikely someone would have the same salary at age 30 as they do at 22 when they’re just starting out. Should you have your 22-year-old salary saved by the time you’re 30? Or your 30-year-old salary?

In other words, am I gunning for $50,000, or $73,870? It becomes a moving target as I make more money.

What if someone makes $50,000 per year for 7 years and then suddenly gets a giant, overdue raise when they’re 29 (or switches careers) and jumps up to, say, $150,000?

Should that person who didn’t earn anywhere near their 30-year-old salary for the majority of their twenties still be expected to have saved enough to match it?

The bottom line is that this rule of thumb doesn’t work very well for the way real life works.

There are too many variables at play, especially specific to the way people earn and how salaries progress unevenly sometimes.

That said, I wanted to understand how this conventional rule of thumb arrived at the number it did to reverse-engineer the save rate it’s suggesting is sufficient.

Assuming “have your salary saved by the time you’re 30” does, in fact, mean your 30-year-old salary, this hypothetical #RichGirl above would have to have $73,870 saved by the time she’s 30.

That means her average save rate would’ve been about 13.5%.

Interestingly enough, 13% was the average American save rate during the pandemic (which was an increase from the “regular” average, which was between 6-8%).

Following this rule of thumb, you’d likely be dubbed good-to-go if you saved approximately 13% of your income each year. Compared to the average American in the average year, you’re doing double duty! Good for you, Sally Saver.

The problem? 13% is nowhere near enough if you want to retire pretty much any time before you’re old and gray.

The Magic Math behind retirement is simple:

You have a 96% chance of retirement success (historically) by withdrawing 4.25% of your total assets each year, once you’ve invested 25x your annual expenses (per Bill Bengen’s 4% rule research in the 1990s, later validated by researchers at Trinity University, though it has been called into question recently).

Let’s make that real, because if this is new to you, your eyes probably just glazed over.

To keep rolling with our example earner above, in the year she earned $63,813 and saved 13%, that means she spent about $55,000.

Let’s say that person always needs about $55,000 to live. In order for her investments to support that level of spending, she’d need to have:

$55,000 * 25 = $1,375,000.

(That is, in today’s dollars. Remember, you have to adjust this shit for inflation.)

With an average of a 13% save rate—assuming that rate stays consistent over time—it would take about 45 years of saving 13% of your income to be able to replace your spending using investment returns.

While this sounds like a literal eternity to me, it does confirm my initial assumptions about where that “your salary by age 30” came from:

Starting work at age 22 + 45 more years of working = retiring at 67. A 13% save rate means you can retire at 67, theoretically, which is pretty in-line with “traditional” retirement planning.

If you flesh out each year of this hypothetical person’s life, having their salary saved by age 30 would mean they’re right on track.

But I don’t really know anyone who wants to work until they’re 67

At least, not doing the same thing they’re doing at 25.

Even if you’re not into the idea of retiring at 35 and spending all your time reading in a park and sipping wine coolers like I am, you’re probably hoping to walk away from your corporate 9-5 job before you qualify for Medicare.

In my mind, there’s no “one track”—my plan is simple. When people ask me how much they should be saving, I think the simplest, best answer is:

As much as you possibly can while still enjoying yourself.

As much as you possibly can.

That means I don’t obsess over maintaining a certain save rate. I just do my best to increase the margin between (a) what I’m earning and (b) what I’m spending every month in some way, whether that be through earning more or spending less.

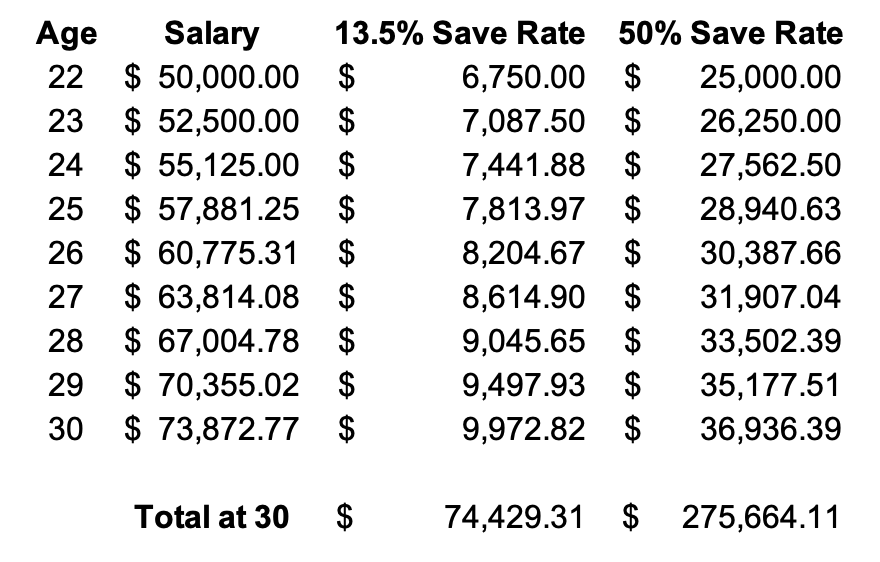

But for the sake of this blog post—because I know you came here for a pithy equation that would assign you a “grade” the way the American education system has brainwashed us to crave—I’d say the ideal save rate we should all be striving for is 50%. Why? A 50% save rate makes you pretty much infallible, because for every year you work, you buy yourself a year of freedom.

Spend half, save half. At a 50% save rate, you can retire in roughly 17 years flat (age 39 or so, if beginning around 22). That’s not to say you’d have to retire, just that the decision would be yours to make: And who doesn’t want to be in control of how they’re spending their time?

Now, obviously that doesn’t account for inflation or the way people actually earn and spend—so use it as a benchmark. A goal! The takeaway is that you’re comparing a 45-year working life vs. a 17-year working life. Check out the difference:

Now, the person would have $275,000 at age 30, instead of $73,000.

And while this nice, neat salary progression lends itself to easy percentages, I know firsthand that salary progression can be quite messy. I’ve earned anywhere from $52,000 per year to $250,000 per year in the last five years, depending on how much I’m working (and for whom).

If you were to tell me I needed 5x my current salary by the time I’m 30, I don’t think I could do it, because there’s no guarantee my earning potential stays on the same path. So instead of making generalizations about 1x, 2x, 3x your salary, etc., I think the better path is this:

How to make this determination for yourself: An exercise

Write down the amount you’ve earned each year until today.

Add the numbers up.

Multiply by 80% (0.8) to determine your (rough, approximate) post-tax income.

Divide that number in half.

That’s the number you’d want to have saved (50% of your post-tax income).

Mine would look like this:

$52,000

$60,000

$72,000

$100,000

$170,000

= $454,000

$454,000 * 80% = $363,200

$363,200 / 2 = $181,600

I should have $181,600 if I’m on the “50% save rate” train. Thanks to the magic of compounding, as of the time of this writing, I’m good to go.

So maybe the real moral of the story is, investing can supercharge this entire equation.

I always recommend Betterment for investing because they’ll basically do it for you. There’s really no catch. As long as you can dump money into the accounts, you’re done.

Of course, knowing how much you can invest every month depends heavily on your income and spending. Check out the Budget Like a Millionaire Masterclass if you’d like your hand held through creating the strongest foundation possible.

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time