The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

August 2020

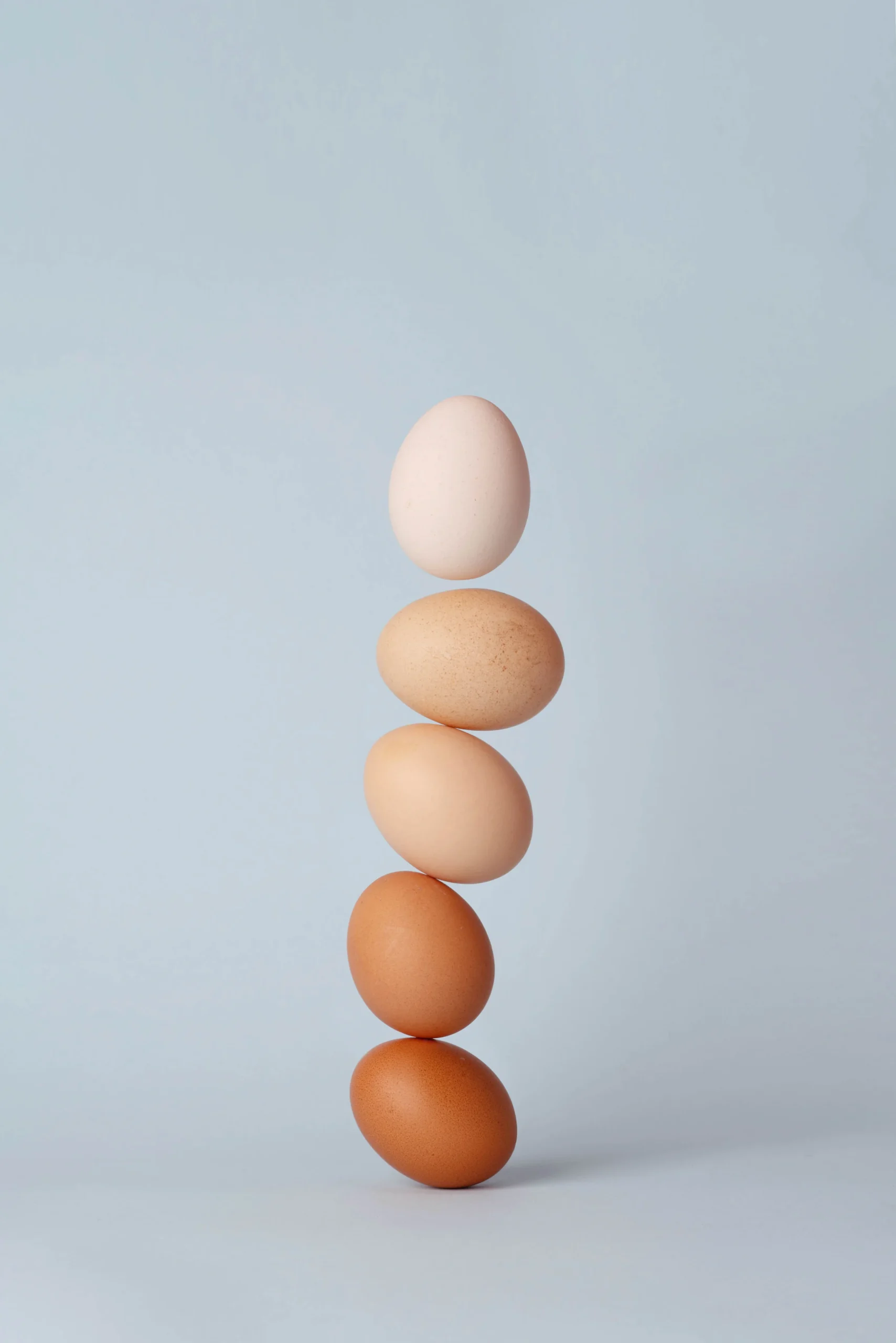

For all intents and purposes of this post, this is your money. We’re going to put these eggs in different baskets.

Welcome to part 2 of “What to Do Once Your Emergency Fund is Stocked,” and get ready to put on your thinking cap. Today, we’re diving into how to most strategically prioritize where you’re investing (and why).

At the risk of sounding like a stereotypical Internet Writer®, go back and read Pt. 1 if you haven’t yet: What to Do After Your Emergency Fund is Fully Stocked. Or, if your emergency fund isn’t fully stocked yet, check out How to Start Building Your Emergency Fund in 2020.

Phew. Self-promotion? Check. Moving on!

Investment priorities

By now, you’re probably convinced that investing makes sense. But “investing” is just about the world’s broadest term, and believe it or not, there are a lot of ways to approach it incorrectly – and most of them are probably beyond the reasons you’re thinking of right now. Most people are not investing $10,000 in a single stock and crossing their fingers; it feels silly and insulting to waste time advising against taking outsized risks to beat the market with picking individual stocks.

Instead, let’s back up a step. If the eggs pictured above represent particular funds to invest in, I want you to think about zooming out a level. We’re no longer looking at which eggs, specifically, to pick – we’re looking at the baskets in which you can put those eggs.

Basket #1: Your 401(k)

If you have access to a 401(k), 403(b), or 457 plan through your employer, congratulations – you have a basket with a $19,500 limit in which the IRS won’t tax the growth.

Ultimately, the reason everyone urges you to use your 401(k) – aside from the possible employer match – is not just because they want you to save for retirement, but because of taxes.

I used to wonder why everyone was so riled up about 401(k) plans. Can’t I just “save for retirement” in a different account? I’d wonder. And yes, there are other options – but the 401(k) is special because it’s a way for you to invest a sizable amount of money for the long run and not be taxed on the interest every year.

PAUSE: Let’s address the IRS-sized elephant in the room

If you have yet to do so, read “Traditional vs. Roth, Explained.” Sorry. I really thought the self-plugging was done, but here we are. This addresses some of the tax basics (emphasis on basics; I am not a tax expert) that underlie the logic in this article and will be a great place to start if you’re fuzzy on the difference between Traditional and Roth retirement accounts.

Back to the 401(k)

All that to say, the 401(k) is your tax magic school bus. This should be the first basket you visit before you even think about doing anything else if you have one. (Looking at you, 2017 Katie: Put down the iPhone and step away from the Robinhood app.)

You likely (a) already have one and (b) already have chosen Traditional or Roth, so here’s the big picture idea that’s important:

You need to contribute at least up to your company match, but shoot for 10% or higher if at all possible.

Remember how we’ve already acknowledged that your emergency fund is fully funded? If you have your token $15,000 in savings hanging out somewhere safe, secure, and (hopefully) high-growth, you no longer need to be saving whatever percentage of your income you’ve been contributing to your emergency fund every month.

Let’s say you make $5,000 per month and you had been saving $1,000 of it. Now you’re fully stocked for emergencies. That extra $1,000 that you don’t need? Straight to the 401(k)!

One caveat: If your employer doesn’t offer a match, the 401(k) is a slightly less ideal first priority. It’s still great (since 401k = $19,500 of investment opportunity that the Feds can’t tax every year), but you have a lot less control over the fees you’re paying in an employer-sponsored 401(k).

The fees aren’t a showstopper for people getting, say, a 6% dollar-for-dollar match, because the extra money the company kicks in will offset any losses you suffer from extra management fees, but it’s something to be conscious of if you know you don’t get a match. Some employers are cutting company matches right now since COVID hellfire is raining down upon company budgets.

In any case, 10% is a healthy figure to aim for in a 401(k) plan. Until you can commit to 10%, I would pause on going any further. However, once you’re comfortably committing 10% to your 401(k) and still feel like you’ve got a little left over every month…

Basket #2: Your IRA (Individual Retirement Account)

If you’re anything like most people I talk to, you probably just said one of two things:

-

What the hell is that? or

-

But I have a 401(k). What do I need an IRA for?

You need an IRA for the same reason you have a 401(k) – tax-free growth, baby. The IRA is a smaller basket – it only allows you to contribute $6,000 per year (as of 2020), but that’s $6,000 per year that generates interest off which the IRS can’t skim the top on an annual basis.

If you don’t have access to a 401(k), this is the no-brainer next-best-option. A few things to note:

-

You have more control over your IRA than your 401(k) because you get to choose the brokerage firm (and the fee structure). I’ll be honest: My Roth IRA is with Vanguard and it’s entirely invested in VTSAX, the Vanguard Total Stock Market index fund. This is volatile; it means I’m 100% in stocks (no bonds). As I get older, I’ll worry about dialing back the risk in this account, but for now, I’m OK with it. (Year-to-date, VTSAX is almost perfectly breakeven as of this writing.)

-

You can open a Traditional or Roth, just like the 401(k). If you can do Roth, I generally recommend it. Here’s why.

-

Betterment offers a Roth IRA with the same low management fees as all their other accounts, 0.25% annually. I dug into my assessment of Betterment a few weeks ago here, but I may do a longer form review soon.

-

The Feds are serious about that $6,000 annual limit, y’all – and there aren’t really any safeguards in place to stop you from going over. Make sure you’re contributing a max of $500/month (if you split your annual contributions into a monthly cadence, like I do), or you’ll be penalized for the amount over the limit. It feels so ironic to be punished for accidentally investing too much for retirement, but tax laws are unforgiving.

All that to say: Your second priority is your (probably Roth) IRA. Max it out at $500/mo. – easier said than done, but it might actually be easier done than expected. If you’re a super saver, you probably aren’t spending this money anyway.

So let’s say you’re chugging along nicely, with your fully stocked emergency fund, 10% 401(k) contribution, and $500 monthly IRA contribution – you’ve got momentum on your side. Let’s see if we can’t squeeze a little more juice out of this equation for you and circle back to the 401(k) for a moment.

Basket #3: Back to the 401(k), briefly

It’s at this point that I’d recommend shuffling a few more percentage points toward your 401(k), if you can swing it. For my high earners or low spenders (or, the holy grail combination: both), you might not even be scratching the surface of your financial capability yet.

Consider this:

Let’s say you make $100,000 per year (this is a high-earner scenario, remember?) and your monthly expenses are $3,000. After taxes, your $100,000/year salary is probably a little over $6,300 a month. Let’s apply the logic above to your salary:

Gross monthly income: $8,333

401(k) contribution at 10%: ($833)

Max out Roth IRA: ($500)

Tax estimate: ($2,000)

Even after you’ve paid your taxes, contributed to your 401(k) at 10%, and maxed out your IRA, you still have $5,000 left. We know (in this example) that your monthly expenses are $3,000, which means you’ve got another $2,000 that we can play with.

I’d recommend trying to get your 401(k) contribution up between 12-15% as the next step, if you can.

And if you still have a little money left over and you want to complete the basket distribution…

Basket #4: A general individual investing account

This is probably what you think of when someone says “investing.” It’s not for retirement, it’s just for building wealth. But since it isn’t for retirement, that means you can kiss your sweet tax breaks goodbye.

You’ll have to file 1099 forms every tax season for an account of this nature and the IRS will tax the growth. (It bears repeating at this point that I am not a tax expert or accountant, I’m just a human being who’s filed her taxes for her investments before. If you want to know more about your investment taxes specifically, you could consider getting a personal accountant to help. Or, my personal favorite recourse: Call your dad.)

But although it’s not as tax-friendly, the individual investing account is a wonderful place to put extra money – much better than stowing it away in a savings account every month. See below for a very important caveat.

Of course, technically the most responsible thing to do would be to avoid an individual investing account until you’ve maxed out your 401(k) at $19,500 per year (that’s $1,625 per month, or a 32% contribution for a $60,000/year salary), but my philosophy is this:

While I’ll need money in retirement no doubt, I’ll also probably need some wealth in the next 10 years to buy a home. Or to have a kid. Or to do any number of things that come before the age of 59.5. I don’t want all of my invested wealth to go toward retirement, because that means I’d have to wait to start regular investing until I could afford to max out a 401(k) – and that might take awhile.

This advice might differ from traditional personal finance or wealth management advice, and that’s fine – money is personal. I simply want to begin growing wealth in a general investment account as I simultaneously increase my 401(k) contribution more and more over time.

I also think there’s something to be said for the habit, momentum, and the power of time that comes from this strategy – for example, there’s a school of thought that says you shouldn’t even open an IRA until you can max out the 401(k). But since I opened an IRA and committed to maxing it out, I’m now (a) in the habit of contributing $500 a month to it and (b) provided with several extra years of compound growth because I opened it earlier than I could’ve if I had focused all my energy on the 401(k). Building a large principle balance early is the best possible thing you can do for your investments. The early years matter a lot to the trajectory of an investment account.

Betterment’s version of this individual investment “basket” is simply called General Investing, if you’re interested.

If you choose to enact this order of priority, you’ll probably have the most going into your 401(k), the second-most going into your IRA, and whatever’s left over going into your individual investing account (unless you’re a supremely high earner, in which case you may be able to invest more into an individual account after maxing out both retirement accounts – wouldn’t know what that’s like; must be nice!).

In conclusion…

This is intended to provide some general clarity around your different options at this stage of life. Don’t feel bad if you can’t yet afford to fill Basket #1. This Easter Egg Hunt is a lifelong affair, and if you get honest with yourself and stay the course, you’ll slowly make your way all the way to Basket #4. It just takes patience (and raises, and discipline… but that’s it!).

See you next week!

Using Betterment

If you’d like to use Betterment, the referral offer right now is one year managed free of up to $5,000 in assets. If you have under $5,000 invested, you’ll skip the 0.25% fee entirely for a year, and if you have more than $5,000, the first $5k is on them.

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time