Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

For the last four years, we’ve spent Thanksgiving with a few of my husband’s brothers and their families in a Colorado ski town (though the trip is far more “cheese boards” than “snowboards”). Every Black Friday after hanging out in the condo’s living room for two days, we venture out to the main village.

There’s one popular store that we always stop in, and everyone else in town always seems to have the same idea. The dimensions of this particular shop were constructed for a place with a population of 4,500 people, so when hordes of visitors descend for America’s ultimate shopping weekend, you have to maneuver inside it by side-shuffling past one another in bulky puffer coats, knocking flimsy tank tops off congested racks.

>

“The modern shopping experience has been reduced to disappointment in both price and fabric tags, stitched hastily into seemingly infinite heaps of junk. ”

I had been keeping an eye out for an oversized knit sweater ever since my go-to wool blend from 2014 suffered grievous injury (a tear) at the paws of Sam Cat during a bout of playtime that turned acrobatic. But as I kneaded the fabric of the sweaters on the display table, I frowned. For $168, I thought, this thing should feel like being tackled by a chinchilla. I fished in the mass of shedding fluff for a fabric tag: 30% acrylic. Disappointed, I dropped the lifeless arm and looked around for something more appealing. Water, water, everywhere, but not a drop to drink.

Sensing the ambient chaos, my three-year-old nephew clocked this activity as Decidedly Not Fun and began to cry, so I offered to check out for my sister-in-law while she took him outside. Finishing up at the register ahead of me, a dad flanked by two teen daughters pinned his elbows to his sides as he wheeled around, eyes desperately charting an exit path. He said to no one in particular, “Let’s get out of here. This place is a zoo.” Preach, I thought—failing to realize that in his metaphor, I was one of the animals on the loose.

Later that night as I sat in bed reflecting on the day, I felt a creeping dissatisfaction that was hard to place. Every once in a while, this sensation of overwhelm flares; this feeling of being surrounded by too much stuff, and not in a charmingly maximalist way. I opened my laptop and began searching for conversations about the apparent dropoff in quality of even expensive products; the way the modern shopping experience has been reduced to disappointment in both price and fabric tags, stitched hastily into seemingly infinite heaps of junk.

It didn’t take long to begin identifying sources of this detectable artificiality: As of 2021, 52% of all fiber production was polyester; that is to say, plastic. The Federal Trade Commission, which regulates things like apparel labels, does not set federal standards in the US for what can be used to make clothing for adults. Even if we aren’t textile or supply chain experts, I think we can feel the truth of this mass cheapening; that the state of commercial culture is life-diminishing. While the complexity and opacity of the supply chains and a lack of regulation makes it hard to generalize, there are studies that show the manufacturing process of the synthetic materials used in textiles creates byproducts known to cause “hormonal imbalance, cancer, nervous system disorders and immunity level reduction in human beings.”

During my searching, a comment on a Reddit thread about quality decline at said popular store caught my eye: “This is happening with absolutely everything, though,” they wrote. “As we want more stuff, but also want it new every year…it’s just not made to last. It’s why I appreciate cultures like Japan[’s], where quality is still treated like an art form. I wish more of the world would adopt this view.”

>

“Normal wear-and-tear is an invitation to trick something out even further (pour gold in the cracks!), as opposed to an injunction to throw it away.”

My Black Friday-induced overwhelm seemed inextricably connected to this deluge. This feeling subsides and reemerges like a tide, but it always seems to swell around the holidays, when already-fever-pitched advertising campaigns go supersonic and we shift into full-blown gift guide hysteria. I usually attempt to remedy it by taking inventory of what’s actually in my care. This urge to account for belongings—to catalog them—has been lifelong. There’s a flash of a childhood memory, gathering all my earthly possessions: my art supplies and Polly Pockets and Halloween costumes and stick-on earrings and picture books. I had laid the collection flat on the family room floor, wanting to contain all of it in my field of vision at once, like a tiny Toys ‘R Us archivist. (I’m sure my parents were thrilled.)

The Redditor’s invocation of Japanese culture was especially noteworthy to me because of the Japanese practice of kintsugi, or the “art of repair.” Translated directly, the word means “golden joinery” and describes the process of restoring an item in a way that calls attention to the wear, “so obvious that it can be considered nothing less than [a] celebration of use,” writes Kathryn Manzella in a blog post about the practice. Normal wear-and-tear is an invitation to trick something out even further (pour gold in the cracks!), as opposed to an injunction to throw it away. The process of restoration itself is “tremendously satisfying,” Manzella writes, infusing a well-worn object with even more energy, as if generating life.

From David Pike in “Traditional Kyoto.”

Before the trip, this cognitive dissonance between the seemingly infinite amount of “stuff” for sale and its utter worthlessness had already begun. Over the previous weekend, I almost bought a new phone. There’s nothing wrong with my current phone—it’s not cracked, it’s barely two years old, and according to last week’s screen time report, I apparently found it useful enough to spend two hours and 15 minutes staring at it each day, picking it up an average of once every 18 minutes. But I had seen the new iPhone—small! pink! barely discernible from my own!—and suddenly, my phone—big! blue! technically perfectly functional!—felt clunky and old.

But the day I planned to make my pilgrimage to the Apple Store, I happened to watch Buy Now: The Shopping Conspiracy and, much like the way that one 2010s fast food documentary put me off chicken nuggets indefinitely, I was horrified to learn what happens to our rapidly discarded tech. Equally shocking were the revelations about the lengths to which companies go to make fixing these products all but impossible. Planned obsolescence and forced replacement. Pictures speak louder than words here:

The Guardian .

The documentary includes the work of Jim Puckett, founder of a nonprofit that hides trackers in electronic waste given to “recyclers” to see where they actually end up. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that recycling centers often just ship the waste to China and Thailand to be pulled apart by hand and thrown in a landfill. According to this report from the Global E-Waste Statistics Partnership, less than a quarter of discarded electronics are documented as being recycled, and since 2010, the waste is outpacing recycling by a factor of five.

My desire to upgrade my phone was smothered in hot shame. When had I become such a sucker for novelty? Had money really been the only thing preventing me in the past from devolving into an instant gratification-addled iPad Kid, frothing at the mouth over some useless feature called “Dynamic Island”? Had the Verizon marketing department’s totalizing ethos of “annual upgrades” infected my outlook to the point that waiting two years made me feel like a Cistercian monk?

“It’s easy to replace your perfectly functional device all the time! We’ll even let you put it on a payment plan!”

The festering dissatisfaction wasn’t just about the shame of my learned consumer impulses—it was finally admitting that the thrill of acquisition wasn’t even all that thrilling anymore. In the midst of my days-long meaning-making exercise, there was a brief diversion to a Pinterest board featuring wool coats and leather loafers and silk pants. I found myself suddenly fetishizing the aesthetic, simply because it felt durable and hearty in the context of so much disposable clothing. The fabrics looked luxurious in an old-timey, classic way, as opposed to the way that expensive clothes are “luxurious” today, that is, in price only: like this $410 Prada tie made of nylon (read: plastic) or this $895 alice + olivia trench coat made of vegan leather (also plastic! 100% polyurethane!).

Against my better judgment, I am tempted to call this mahogany-and-elbow-patch style “Yassified Jordan Peterson Core.” If the loafer fits.

I realize I’m wading into Luddite territory, but my point is that very little of this hyperabundance actually feels good, satiating, life-affirming. All the new and exciting access we’ve been granted often feels gimmicky, at once overpriced and cheap, like being told a mediocre consolation prize is actually a treasure worthy of untold sacrifice. This cultural shift transcends goods and infiltrates our interactions with individualized, app-based services: As Chelsea Fagan notes, we’ll never get competently designed high-speed rail in this country, but at least we’ll have a million ways to get a single donut delivered at 3 AM for $25, the transportation innovation equivalent of empty calories. If you adopt the standard high-income, “professional managerial class” millennial way of life designed in Silicon Valley boardrooms (work from home, install a home gym, order everything you need from a plethora of apps powered by a low-wage temp workforce), you don’t even need to leave your house (so there’s no need for that public transport after all!). Right-wing think tanks often point to this excess of crap as proof of progress, that the “supposed decline of the middle class” isn’t real, because poor people have flat-screen televisions and microwaves and two-day shipping. Okay! Sure!

This is the cycle many of us find ourselves inadvertently enmeshed in: A period of prolonged, exhausting work might inspire an initial bout of financed overspending, which leads to the need to work and earn more. This turn of events consumes even more of your time and energy, which leads to seeking even more readily available dopamine and convenience services, and so on. “The sense of relief these cheap experiences provide to consumers who are experiencing an entirely related squeeze obscures the fact that these companies’ biggest breakthroughs have been successfully monetizing the unyielding stresses of late capitalism,” wrote Jia Tolentino in her 2019 essay “The Story of a Generation in Seven Scams.”

>

“Shame is not a sustainable motivator; at least, not as long as rapid accumulation continues to scan as even superficially fun or aspirational.”

This is the environment that produces things like the viral Temu “croissant lamp,” which became an instant internet sensation when a woman who ordered from the platform (“Shop like a billionaire!”) noticed her light seemed to attract an unrelenting parade of ants and, upon further inspection, realized it was literally a croissant slathered in resin with hasty wiring inside. (“Amazon does have available croissant lamp options that aren’t made from bread,” notes Food & Wine coverage of the debacle, affiliate link locked and loaded, without any apparent awareness of how absurd that sentence is.)

But scolding ourselves or others for ordering pastry lamps from Temu isn’t going to change anything. Shame is not a sustainable motivator; at least, not as long as rapid accumulation continues to scan as even superficially fun or aspirational.

Ideally, some regulatory body would step in and set standards about materials or production or, I don’t know, anything. But it’s not just regulatory—it’s cultural. To end the scourge of 52 “micro seasons” and the inevitable quality decline that follows, an alternate way of being must become even more fashionable, alluring. My thoughts drift again to interrogating that sweater with the snag hanging in my closet, and why I perceived a single blemish as evidence that an otherwise-dependable 10-year-old item should be replaced, even as I’m feeling inexplicable resistance to doing so.

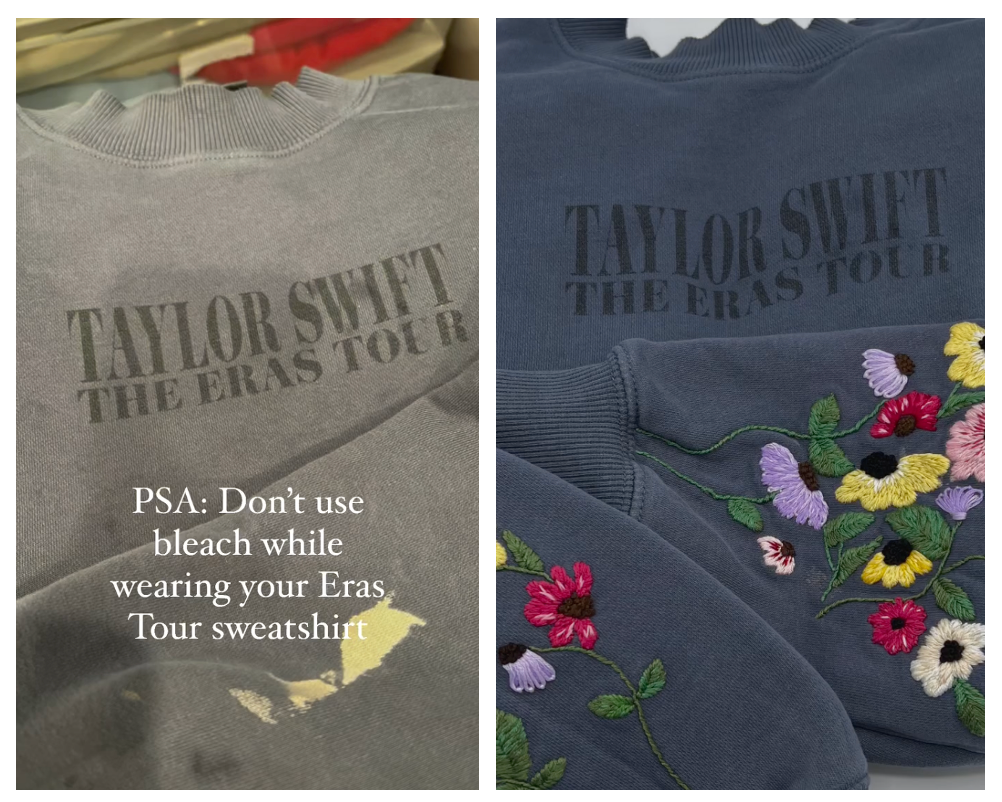

What is this tossing impulse, if not a capitulation to a mass production environment that prizes newness over all else? I thought again about kintsugi, and wondered if my visceral aversion was a sign to try something else, remembering this video from a woman who salvaged her favorite sweatshirt from a bleach stain by embroidering over it:

What a coincidence! This happens to be my favorite sweatshirt, too. #JustLikeOtherGirls

It’s easy for me to believe that there’s something inherently more attractive, interesting, and cool about a little patina and a creative repair; something made of a fabric that didn’t originate in a fossil fuel. There’s a twinkle of this point of view in the surge of “homage” red carpet fashion. As Emily Kirkpatrick says on a recent episode of The Review of Mess, celebrity “It” Girls are favoring archival pieces over new designs.

The path forward will not be paved with stronger consumer financial restraint, but with genuine preference—prizing something with history more than something with tags. In this framework, the distended temptation to transact rightsizes again. Maybe this small shift in taste could become the first step in repairing something even bigger.

December 11, 2024

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time