How to Optimize Your Taxes for Early Retirement and Save Thousands

February 1, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

I have to use sexy shots of the Greek coast for articles about taxes, otherwise nobody gives a shit. This is my struggle.

I want to disclaim three things before I get into this:

-

I’m not a tax professional (surprise, surprise!). I’m not an accountant, and I intend to USE an accountant during tax season this year to help me sort out my different streams of income and itemizations so I don’t end up getting absolutely obliterated by Uncle Sam (as I anticipate I will right now). However, I have to say… after researching for and writing this post, I feel more equipped to figure out how to accurately estimate my own taxes, so #bonus there.

-

When it comes to financial independence math and tax law at a super impressive level, Mad FIentist is your guy. He’s a whiz, and he’s known in the community for being the best of the best. The only reason I feel like you’d come to me instead is because you might consider me the more relatable equivalent: Mad FIentist reads tax law in his free time and probably writes differential equations in his sleep. I barely squeaked by Calculus I. I hope that my interest in and surface-level knowledge of this stuff convinces you that if I can figure it out, anyone can. No PhD required. Consider Mad FIentist your primary source and me your secondary, if we’re talking in high school research paper terms.

-

The reasoning fleshed out here is for early retirement, but has applications in traditional retirement. There are two major tenets of early retirement that don’t matter in “traditional” retirement (when I say early, I mean leaving the work force in your 30s or 40s, and when I say traditional, I mean late 60s or early 70s): the first is that you’ll be living off a smaller amount of money than most people anticipate when they talk about retirement ($40,000 per person, per year as opposed to $90,000 per person, per year, for example), and the other is that you’ll need access to your retirement accounts about 30 years before they’re intended to be used.

Because we’re talking about tax optimization for early retirement here, I reference “conversions” a few times in this post – that’s what enables you to use your retirement accounts when you’re 35 years old instead of 65 without a penalty. I did a deeper dive here, but this post is probably a better starting point.

When we talk about optimizing our taxes for our retirement investing plans, most people are faced with this simple question:

Would you like to pay your taxes now or later?

The good thing about retirement-specific investment accounts is that they provide some additional tax flexibility, and if you play your cards right, you could be walking away with virtually untaxed funds. It doesn’t sound possible (or legal), but keep reading.

In other words, your choices are: Would you like a Roth (pay taxes now) or Traditional (pay taxes later) retirement account?

The natural next step question is, Do I think I’ll pay more in taxes now, or more in taxes when I retire?

This requires us to take a step back and talk about how we’re taxed.

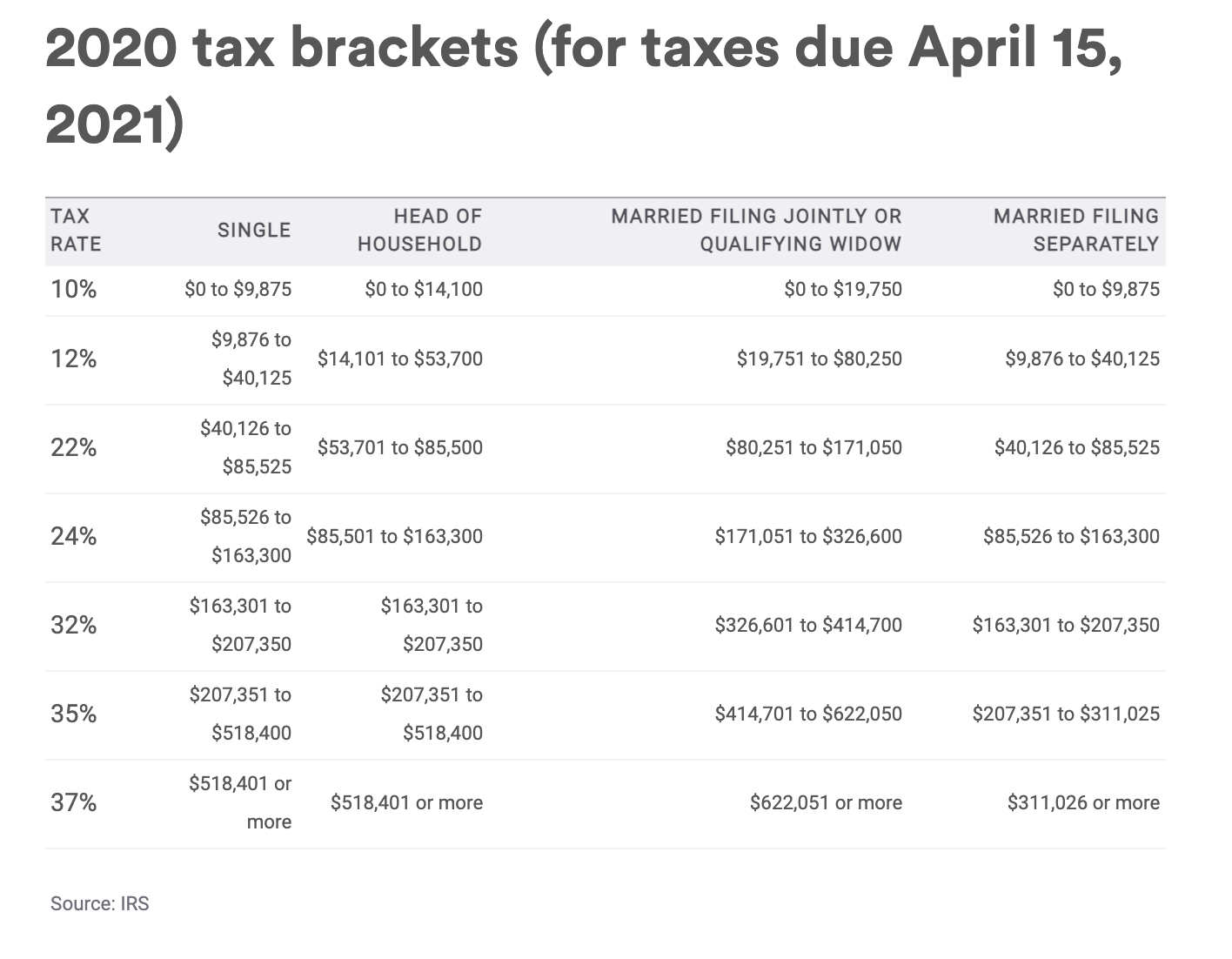

In the United States in the year 2021, we have a progressive tax scale, and this means your entire income isn’t taxed at the same rate. I’m using numbers for 2021 taxation (which you’ll pay in April 2022).

For example: If you’re legally single and make $100,000, you’re funneled into the first four tax brackets.

-

Your first $9,875 is taxed 10%, which means you pay $987 in taxes on this amount (10% is the income bracket for amounts $0 to $9,875)

-

Your next $30,249 is taxed 12%, which means you pay $3,629.88 in taxes on this amount (12% is the income bracket for amounts $9,876 to $40,125)

-

Your next $45,399 is taxed 22%, which means you pay $9,987.78 in taxes on this amount (22% is the income bracket for amounts $40,126 to $85,525)

-

Your last $14,474 is taxed 24%, which means you would pay $3,473.76 if it weren’t for the “standard deduction”

-

24% is the income bracket for amounts $85,526 to $163,300; however, thanks to the standard deduction of $12,550 for single people, you can wipe $12,550 off the top line of your gross income. In this case, you’ll be taxed on $100,000 minus $12,550, or $87,450.

-

This means that, while without the standard deduction you’d have that $14,474 chunk of change being taxed in that 24% bracket, WITH the standard deduction, you only have $1,924 of your income in that 24% tax bracket (the cutoff for 24% is income above $85,526, so the standard deduction drops you right above the cutoff at $87,450).

-

If only $1,924 is taxed at 24%, that means instead of paying $3,473.76, you’d be paying $461.76. Hell yeah!

-

This means, in total, your tax bill (based on 2020 tax brackets, for taxes due in April 2021) is $15,066.42 – so even though your $100,000 income registers in the “24% marginal tax bracket,” that can be misleading – because your $15,066.42 is only about 15% of your total income, not 24%.

This is where the term “effective tax rate” should enter your consciousness. Your effective tax rate, or the percentage of your income you’re ACTUALLY paying in taxes in this $100,000 income example, is 15%. If you’d like to check out the 2020 tax tables, Bankrate lays them out here. You can funnel your income through the brackets in the same way to figure out your effective tax rate, too.

Now that we understand how income taxes work, let’s talk about optimizing

The primary way you can “hack” your taxes is by deferring your income to be taxed at a point in time that’s optimal for you.

For example, if you make $150,000 today, your effective tax rate is 18%, or $27,104 in taxes owed (I just applied that same “funneling” treatment to $150,000 minus the standard $12,550 deduction for singles, so the taxable income that got chopped up and taxed in the different brackets was $137,450).

The logic that early retirees believe is this:

If I’m only going to be using $40,000 worth of “income” in retirement (in other words, withdrawing $40,000 per year from a retirement-intended investment account), that means – in today’s tax brackets with today’s deductions – I would only be on the hook for a taxable income of $40,000 minus $12,550 – meaning I’m only paying taxes on $27,450 of taxable income.

When we apply our funneling exercise above to $27,450, we see the following:

Your first $9,875 is taxed 10%, which means you pay $987 in taxes on this amount (10% is the income bracket for amounts $0 to $9,875)

Your next $17,575 is taxed 12%, which means you pay $2,109 in taxes on this amount (12% is the income bracket for amounts $9,876 to $40,125)

You’d owe $3,096 in income tax on your $40,000 withdrawal from the retirement account. Your effective tax rate would be just 7%, compared to your effective tax rate on $137,450 in your working years of 18%.

(As you probably remember from the “How to Use Your Traditional 401(k) in Early Retirement Without the 10% Penalty” post, there’s even a way to guarantee you actually never pay taxes on the amount – by strategically converting part of the $40,000 out of your 401(k) and supplementing the rest with a taxable investing account.)

But for the purposes of this exercise, we’re talking the simplest of simple comparisons: Paying your tax in your current income bracket, or paying it later when you’re withdrawing less.

Of course, because you JUST learned about progressive taxation, you’re probably thinking: Wait, so how does progressive taxation play into this?

Great question.

So let’s keep running with this $150,000 situation. Someone who’s pursuing FI is probably trying to cobble together as many streams of high-paying income as they can to reach financial independence, so if you’re really hustling, it’s not unlikely that you’ll reach this milestone before long.

If I’m making $150,000, I’m probably intending to max the shit out of my 401(k).

Let’s look at those brackets again:

From the Bankrate link above.

Pre-tax accounts allow you to eliminate some of your highest taxed income from your tax bill and defer it for later

We know that after the $12,550 standard deduction is applied to $150,000, our taxable income is $137,450, right?

By looking at the chart, we can see that our money from $85,526 up until $137,450 is in the 24% tax bracket, which means we’ll pay $12,461.76 in taxes on the chunk of money in our highest income bracket alone. That’s a lot of money. How do we eliminate some of it? Glad you asked.

The Traditional 401(k) is basically the magic tax vehicle that allows you to drive away more of your money to lower your taxable income – this is what people mean when they say something is “tax deductible.” It means the IRS is going to shave that amount off your taxable income.

In short, you’re eliminating as much of your most highly taxed income from the picture in your working years by contributing it to pre-tax accounts. Then, when you’re ready to begin using it later, you can strategically perform the “conversions” (more on that here) in years where you have little to no other earned income – that way, you’re paying 7% on the money instead of, say, the 24% bracket it would’ve been in, had it been taken off the top line of your income to be taxed for a Roth account (or, as we mentioned in the previously linked article, completely tax-free, depending on how much you’re converting).

When we opt for a Traditional 401(k), we can contribute a tax-deductible $19,500 per year – this means you can subtract another $19,500 from that $137,450. Now, your income is “only” $117,950 in the eyes of the federal government.

There’s a lot less money in your 24% bracket now – the money between $85,526 and $117,950, or $34,424 that’ll be taxed at 24%: $7,781.76 paid in taxes, instead of $12,461.76.

So what does that mean? What do you do now?

For starters, it means you’re saving approx. $5,000 in taxes “this year” (in this hypothetical). It also means that, in 5-10 years when you convert your first $40,000 from Traditional to Roth (in the Roth IRA conversion ladder described in the post linked twice above), your effective tax rate (presuming they stay in line with where they are today) would be just 7%, or about $3,000.

How to double down

Here’s where you can double down on the goodness: That $5,000 you’re saving on taxes? You can invest it in another account, like a Roth IRA or taxable investing account. That way, you’re optimizing your tax savings and investing even more, rather than handing that $5,000 over to the government.

Of course, taxable investing accounts are nice at the withdrawal stage if you’re withdrawing $40,000 or less as a single person and living off it – the long term capital gains tax for $40,000 or less per year (for a single person) is 0%. This is just a fun manipulation of the laws around long term capital gains taxes: People with incomes under $40,000 don’t pay long-term capital gains taxes, so if you’re retired and withdraw less than $40,000, you won’t pay taxes on it.

Considerations

This mastermind plot really doesn’t make sense if your earned income right now is fairly low, or if you intend to use a lot of money in retirement. If your tax rate will be a lot higher in retirement than it is now (and who can really be sure, if your retirement timeline is 30 years away?), you’d rather pay taxes now with your current effective tax rate than risk it later. This is why Roth makes sense for a lot of people, but may not if you intend to retire earlier than 59.5.

For people who intend to retire early (and with a timeline more to the tune of 10 years than 40), you don’t have to make as many assumption jumps.

If you’re like, Okay, Katie, I think I get it… but I want to see it in action!, you can check out my post “What Actually Happens When You Retire Early?” where I take you step-by-step through how I’d enact this plan for myself.

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time