The Ultimate Traditional 401(k) vs. Roth 401(k) Debate: Traditional Wins

June 28, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

2025 Update: There’s a much more in-depth breakdown of this thesis in Chapter 6 of Rich Girl Nation. If you’d prefer to listen to me explain it, check out this episode of The Money with Katie Show. The math in this post still uses 2022 contribution limits, but the logic remains!

There are so many diehard Roth fans out there that I feel like I have to duck and cover when I say this, but I’m going to say it:

After doing the research that led to today’s post, I have no idea why anyone would ever opt for a Roth 401(k). Today, I’ll show you why.

It’s worth making the immediate caveat here that your Roth IRA is still a tax-advantaged vehicle I’d recommend using, and maybe even in tandem with what I’ll show you today—but my intent is to show you why the tax deferral benefits of contributing the maximum amount ($20,500) to a Traditional 401(k) simply can’t be beat, even if effective tax rates in the future double.

It all comes down to one very simple, yet powerful tweak:

You have to invest the tax savings.

Let me repeat:

You have to invest the tax savings.

While I don’t want to spend too much time today on background basics, let’s get on the same page about the difference between Roth and Traditional:

When you contribute to a Traditional retirement account, you don’t pay taxes on the contribution in your current tax year. Since contributions would be taxed (if they were Roth) in your highest marginal tax bracket, the savings are usually at least a few thousand dollars.

The benefit of the Roth account is that—while you do pay taxes in your highest marginal tax bracket this year—you don’t have to pay taxes on the growth later.

That begs the question: What happens “later”? How is Traditional 401(k) money taxed in retirement?

Let’s talk really quickly about what happens “later”—when you withdraw your money from your Traditional 401(k), you have to pay taxes on it, right? That’s the deal you signed up for.

But you don’t pay the taxes in your highest marginal bracket.

The money that you convert from Traditional to Roth in retirement is treated like earned income, which means you’re taxed on it as if it’s income from a job.

That means you get a standard deduction. That also means you’re taxed “bottom-up” instead of “top-down.”

In other words, if you know anything about our progressive tax system, you know that income from your job is taxed from the lowest tax bracket up (the first $10,000 or so is taxed at 10%, the second chunk of about $30,000 is taxed at 12%, so on and so forth).

While I thought I made a pretty compelling argument for why Traditional made more intuitive sense (skip the top-down taxes now, and pay bottom-up taxes later), I got some pretty intense feedback from Roth lovers who said that the tax-free growth in a Roth account still made it the obvious better choice.

I wasn’t so sure, especially because the “tax-free growth” argument for Roth ignores a big present-day benefit of the Traditional—the tax savings that you can invest elsewhere.

Even though people always say that tax rates will go up, I knew we were still comparing today’s marginal rates to the future’s effective tax rates (since the Traditional 401(k) conversions are being taxed like ordinary income when you withdraw them).

I decided to do a little experiment.

Before we launch in, my standard disclaimer stands: Trying to project anything 50 years in the future is a fool’s errand, at the end of the day. We’re just using averages and the current tax code to try to make the best choices we can for the future based on what we know today, but I’m not wholly convinced I won’t be an immortal half-robot living on Mars in 50 years from now exchanging CatCoin for organic oil changes.

The methodology

There are a few things we have to get on the same page about upfront.

I’m using averages that I’d consider pretty conservative so nobody slides in my DMs with a pitchfork to let me know that I’m an optimistic dumb bitch with a public relations degree (though… guilty). The important thing is, these same averages apply across the scenarios, so if Traditional is helped or hurt by one of our assumptions, Roth would be, too.

Here are the parameters for my little mad scientist Saturday night:

-

25-year working timeline—doesn’t really matter when you start, but to make it feel more real, we’ll pretend we’re starting to invest at age 30 and retiring at age 55

-

Then, we’ll flesh it out another 25 years (to age 80) to demonstrate how the trend continues, though you’ll be able to extrapolate for yourself indefinitely

-

3% avg. inflation (also applies to the contribution limits, which will go up by 3% per year, too)

-

7% avg. rate of return (that means the “real” rate of return in these scenarios is actually about 4%, because it’s a 7% return minus 3% inflation – that’s really, really low, and I chose to do it that way to show that the stock market doesn’t have to go on a wild bull run in order for this to be true)

-

Analyzing three situations: Earners in today’s 12%, 24%, and 32% marginal tax brackets (remember, your marginal tax bracket might be lower than you think after your standard deduction, so be sure to subtract the standard deduction from your gross income before you assign yourself into one of these buckets)

For the purposes of today’s exercise, we aren’t going to worry about state taxes. That may feel like a sloppy oversight, but since some people reading this work in a state with 0% state income tax and others work in a state that has 12% state income tax, I’m not going to mess with adding in a tax that’s so wildly variable.

Plus, most people retire in a different state than they work in, which would impact how their withdrawals are taxed – including hypothetical state taxes would muddy the waters for our “earning” taxes vs. “withdrawal” taxes because there are too many variables. That said, it’s something you can plan for.

It’s also worth noting (if you’ve read any of my other 401(k) hacking mania before) there are creative ways to get your money out of a Traditional 401(k) tax-free, too. But let’s pretend you’re not being strategic or savvy by pulling strategic amounts from different accounts and optimizing your tax strategy—you’re just pulling the full amount you need from a 401(k) or other taxable accounts for the sake of this analysis.

The key is this: All that really matters is the amount of money being put in the accounts, because we can equalize everything at retirement by assuming a 4% safe withdrawal drawdown of assets.

After all, you can’t spend money that’s not there—if someone wanted to make sure they didn’t run out of money, they’d more or less have to follow the 4% rule in retirement (give or take a few basis points, of course), so we’ll be simplifying details by using the following parameters:

-

Person who contributes the maximum, inflation-adjusted contribution to their 401(k) (or 401(k)-equivalent account) over 25 years of a working life (I’ll run it for 12%, 24%, and 32% marginal tax brackets to show the difference)

-

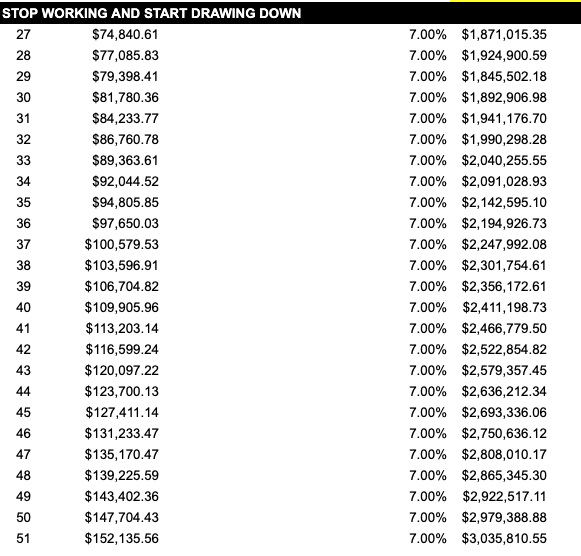

Starts drawing down the inflation-adjusted 4% safe withdrawal rate amount in year 26, then increases that withdrawal rate by 3% per year for inflation

-

To determine the tax rate they’d face based on today’s tax code, I extrapolated backward to figure out what their “year 26 4% drawdown amount” would be worth in today’s dollars, assuming the tax brackets will continue to shift up with inflation (in other words, if you’re withdrawing $44,000 today and have no other income, your effective tax rate as a married person is 4.3%—in 26 years, the inflation-adjusted amount is $92,000, but it’s theoretically taxed at the same effective tax rate since the brackets would go up with inflation, too)

-

To calculate the effective tax rate on certain levels of income withdrawals, I used this SmartAsset calculator—if you use it to play around, remember to only look at the first line item (federal tax) and state/local tax, and eliminate the FICA tax line item since those don’t apply to your retirement withdrawals

This is where everyone hollers about tax rates going up, so to address that, the other round of projections we’ll dive into double the effective tax rate to reflect higher taxes in the future.

The thesis is pretty straightforward: If you invest in a Traditional 401(k) and capture the tax savings (in your marginal tax bracket) by investing that amount of money saved somewhere else (whether a Roth IRA or brokerage account), you fare better than if you’d just contributed the amount to a Roth 401(k) and paid the taxes in your working years.

My ultimate recommendation to totally bone the system and leave the IRS in the dust is to invest the tax savings in a Roth IRA (but you could also use a taxable brokerage account). Think about it: You’ll be investing your tax savings each year from your Traditional 401(k) contribution to a Roth IRA. You’ll never pay taxes on that Roth IRA ever again, thereby giving you both (a) tax diversity and (b) access to the entire amount you see in the tables below.

Remember, withdrawals in retirement are taxed like ordinary income, less your FICA payroll taxes.

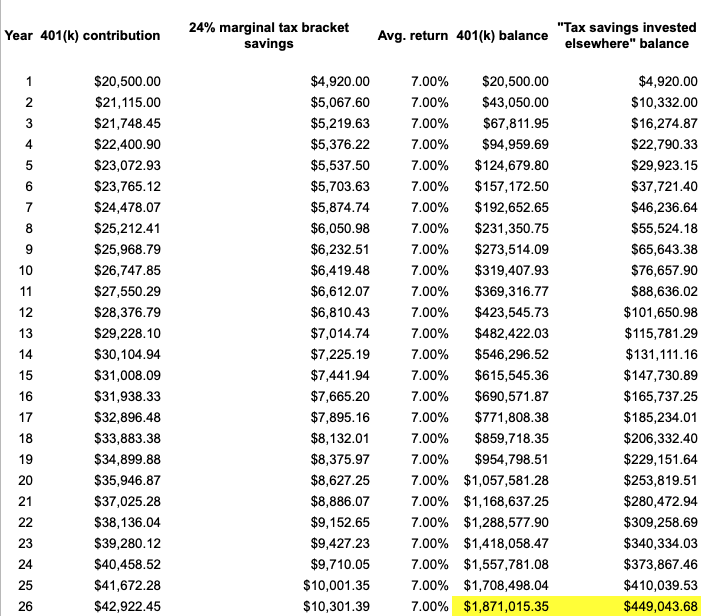

Here’s your 25 years of contributions and invested tax savings, netting $1.8mm in your 401(k) and $450,000 in your other account where you invested your extra take-home pay. Time to retire and hit the club, ladies.

You end up with about $1.8mm in your 401(k), all pre-tax funds, and about $450,000 in your “other” account—that could be a Roth IRA or a taxable brokerage account. The Roth IRA is likely the more optimal choice, but you do you—they’re your tax savings.

The obvious caveat to note here is that—had you contributed to a Roth 401(k)—your $1.8mm balance would be able to be drawn down tax-free, but you wouldn’t have the other $450,000 that you generated in the Traditional 401(k) example by investing the extra take-home pay you had from your tax savings.

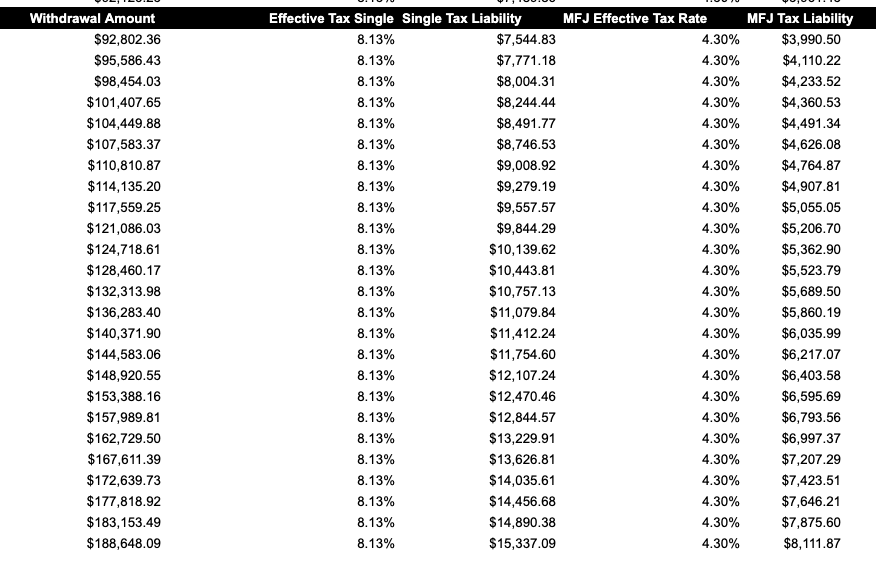

Now it’s time to start drawing down, right? You’ve retired, you’ve got your ~$2.3mm between your two accounts, and it’s time to fuck around and find out what your safe withdrawal rate is (4%): $92,802.

Of course, we know that this has the purchasing power of around $44,000 in 2022 dollars.

So you’ll withdraw your $92,000 ($44,000 in 2022 purchasing power) and pay your taxes on it.

How much of that $92,000 can you use? Well, you’ve gotta set aside some of it to pay your taxes, right? So how much?

If you’re single, you’ll set aside about $7,500 to pay the taxes (an 8.13% effective tax rate, based on today’s rates) and if you’re married, you’ll set aside about $4,000 to pay the taxes (a 4.3% tax rate, based on today’s rates).

Here’s what that looks like fleshed out (remember, you don’t pay FICA taxes anymore, and your federal taxes are calculated “bottom-up,” so the effective tax rate in retirement is lower):

In year 1 of retirement, that leaves you with about $85,000 if you’re single and about $89,000 if you’re married after you pay your taxes.

It’s obvious that your effective tax rate on your withdrawals is lower than your marginal tax rate would’ve been in your working years had you contributed to Roth (in other words, you’re paying 8 cents or 4 cents per dollar in taxes in retirement as opposed to 24 cents per dollar in taxes on your would-have-been Roth contributions).

That’s kinda the rub, right? You end up with more money by contributing to the Traditional if you’re investing your tax savings, too; a Roth hypothetical would look like the below, with a person contributing post-tax dollars to their 401(k) and ending up with $1.8mm total, instead of the “Traditional + invest the tax savings” person who ended up with $2.3mm.

That’s because you used the “tax savings” to pay the taxes. Now, you’ve got $1.8mm of Roth, tax-free money to withdraw.

Again, let’s assume you’re withdrawing 4% in line with the safe withdrawal rate:

No taxes to pay, but 4% of your smaller balance is a smaller withdrawal amount.

There you have it: You can still withdraw 4% of your total balance, and you don’t have to pay any taxes on it, but you end up with a tax-free withdrawal of $75,000, as opposed to your taxable (or partially taxable) withdrawal in the previous example of $92,000, or a net $85,000/$89,000 after tax.

That’s the simplest way to flesh out these two scenarios to show how the invested tax savings is a superior strategy.

The 12% and 32% bracket examples are in the document, linked here and available for you to copy and play with.

Spoiler: The 12% bracket example nets a Traditional + tax savings outcome of $2.1mm and a net drawdown ability (4% less effective tax rate) of $77,000 for singles and $80,600 for married, as opposed to a Roth outcome of a tax-free $1.8mm and $75,000 annual drawdown. The 32% bracket example is (unsurprisingly) most extreme; with a difference in net income for married filing jointly of $20,000 per year less for those who chose Roth instead of Traditional + invest the tax savings.

So the obvious next question is… what happens to our Traditional + tax savings if tax rates go up?

The short answer is that the whole “effective tax rate + no FICA taxes” thing tends to do quite a bit of heavy lifting for lessening our tax burden in retirement.

Besides that, you’re likely noticing that “the inflation-adjusted amount of $44,000 per year to live on” is not a whole lot—the reality is that, unless you’re saving and investing a ton of money (which is usually only made possible by MAKING a ton of money and being in a high tax bracket already), you can end up with $2mm and still not have THAT much to withdraw safely without depleting your principal balance.

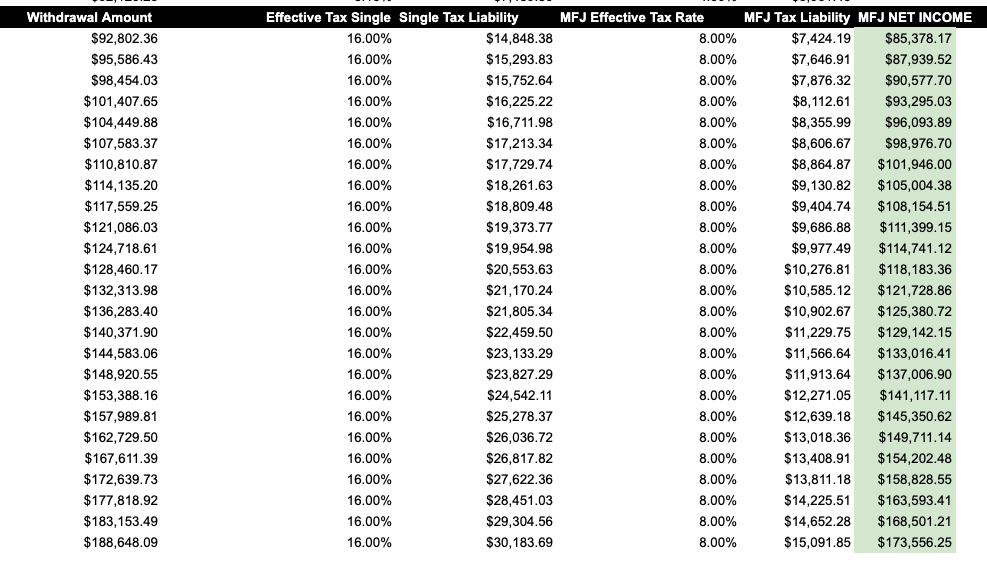

All that aside, let’s say they do go up. Let’s say your effective tax rate doesn’t just go up, but it doubles.

Then what happens?

In our 24% example, that means our single Rich Girl’s tax rate jumps from an effective rate of 8% to 16%. She ends up paying about $15,000 in taxes and nets about $78,000. Woof. The married couple fares a little better; their effective tax rate doubles from today’s rate of 4% to a hypothetical 8% and they end up paying $7,400 in taxes and netting $85,000.

Still, both fare better than the completely tax-free Roth withdrawal of about $75,000, rounding up.

Again, that’s if effective tax rates double in the future—the Traditional + invest the tax savings still comes out on top.

Here’s the same drawdown + taxes breakdown, but with effective tax rates doubled.

Conclusions

As stated before, I’m a public relations major with access to Excel and the tax code. I’m not an economist or financier, so it’s possible there are holes in this reasoning.

And of course, we’re projecting 50 years into the future and doing so in a vacuum. There are other factors at play in people’s lives that don’t allow things to play out this neatly in real life.

That said…

Damn, I’m pretty confident in the fact that it proves the Traditional 401(k) is almost always going to be the preferable choice—as long as you invest your tax savings.

If you don’t invest your tax savings, well… yeah. You probably should’ve picked Roth.

But across the 12%, 24%, and 32% tax brackets, based on the way the progressive tax system works today, Traditional is your best option if you invest the tax savings each year. That doesn’t necessarily mean rates can’t go up—as you saw, the effective tax rates doubled and you still ended up ahead in the 24% bracket with Traditional + investing the tax savings.

And while it’s possible in your earning years you’ll fluctuate wildly between marginal tax brackets (I’ve been in three so far), the fact that the outcome was the same for all three (Traditional being preferable) should assure you that it probably doesn’t matter.

It all comes down to (a) effective tax rates and (b) investing your tax savings with the Traditional. Because your contributions are taxed top-down and your withdrawals are taxed bottom-up, your withdrawals will always be taxed more favorably than your contributions (assuming, of course, the progressive tax system doesn’t totally disappear).

Like I said—if you really want to screw the tax man, invest your Traditional 401(k) tax savings each year in a Roth IRA. That way, you can have your tax-free growth cake and eat it, too.

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time