In These Tax Brackets? The HSA + High-Deductible Plan Might be Cheaper for You [2025]

August 14, 2023

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

As anyone who’s been in the same room as me when the topic of tax savings comes up knows, pre-tax investment vehicles are like my inner 12-year-old girl’s Justin Bieber. If my husband would let me put up a poster on our bedroom wall of the US’s tax-efficient trifecta (401(k), Roth IRA, HSA), I would.

The HSA—or Health Savings Account—in particular is a wunderkind (not to be confused with the Flexible Savings Account, or FSA, which is “use it or lose it” and doesn’t roll over year-over-year). To spare you the longer diatribe, here are a few key points to know:

-

The HSA is different from the 401(k) as a tax savings vehicle because—if you make payroll contributions—you don’t pay the 7.65% FICA tax on them.

-

The HSA is the only investment vehicle that has the potential for funds to go in tax-free, be invested and grow tax-free, and come out tax-free, if they’re used for qualified medical expenses.

-

If you don’t end up using the money for qualified medical expenses, your HSA functionally morphs into an IRA when you turn 65, making it a wonderful complement to your other retirement accounts later in life. (You’ll pay taxes on your distributions like you would with a Traditional IRA if you don’t use them for medical expenses, but there aren’t any penalties for doing so.)

-

Lastly, there are no required minimum distributions! While the government might force you to begin taking withdrawals from your other pre-tax accounts after age 73 depending on the balance, the HSA isn’t subject to these.

COOL. So we’re all on the same page about the HSA being a slept-on tax vehicle.

Now that we know that, let’s talk about who’s eligible: Certain people with high-deductible health plans.

Should I get a high-deductible health plan just so I can have an HSA?

Well, maybe. As with all things financial, it depends—but there’s a framework that might help. (And it’s worth stating explicitly: This discussion assumes your only concern when picking a plan is financial. If you have specific health concerns or doctors you need to make sure you can see in-network, then your health will of course be the number one priority!)

If you’ve got an employer who will pay for all your medical expenses with no deductibles or premiums (shout-out to my past employer, Meta; Zuck, you’re the realest for the totally free healthcare), then yeah…I’d probably take that deal 11 times out of 10.

But what if you’re presented with a smorgasbord of confusing options? A PDF packet so thick it makes your eyes water? Then what?

You might have a few choices—some with high deductibles, and others with low ones. “High-deductible” is defined by our #BoizAtTheIRS as any health plan with a deductible higher than $1,650 for a plan covering just you, and $3,300 for a plan covering your family.

Moreover, the maximum out-of-pocket costs for these plans are $8,300 for plans covering just you, and $16,600 (gulp) for family plans.

I don’t know about you, but I’d do some pretty questionable shit for a deductible as low as $1,650. Mine is $2,500 for a plan that just covers me, and my guess is that many of you will have access to a high-deductible health plan. (If you’re like, “What in God’s green pastures is a deductible?”, read this post for a healthcare primer about premiums, deductibles, copays, and more.)

More often than not, a high-deductible plan will have lower monthly premiums than your alternate options. You can calculate your total maximum costs each year by adding up:

-

12 months of premium costs (i.e., what’s being taken out of your paycheck to pay for the plan). If your insurance costs $200 per month, you know you’ll pay at least $2,400 per year in premiums even if you never set foot into a doctor’s office.

-

Your out-of-pocket maximum (which is a limit that’s higher than your deductible, because the insurance companies are excellent at coming up with convoluted ways to continue passing the buck to you after you hit your deductible). The silver lining is that it should represent the most you’d possibly be on the hook for in a given year. (Key word: should. If you spend on services that your plan doesn’t cover, that’s not included in this limit.)

Then, when you’re debating between the low-deductible plan and high-deductible plans, you can ask yourself at a high level:

-

Do I want to pay more per month but (probably) have a lower deductible and out-of-pocket maximum?

-

OR, would I rather pay less each month but (probably) risk it with the higher deductible and out-of-pocket maximum?

Making matters more complicated (yay!), sometimes these plans involve varying “copays” or “coinsurance” that can make the analysis a little trickier.

For example, Henah and I were comparing health plan options the other night and noticed this:

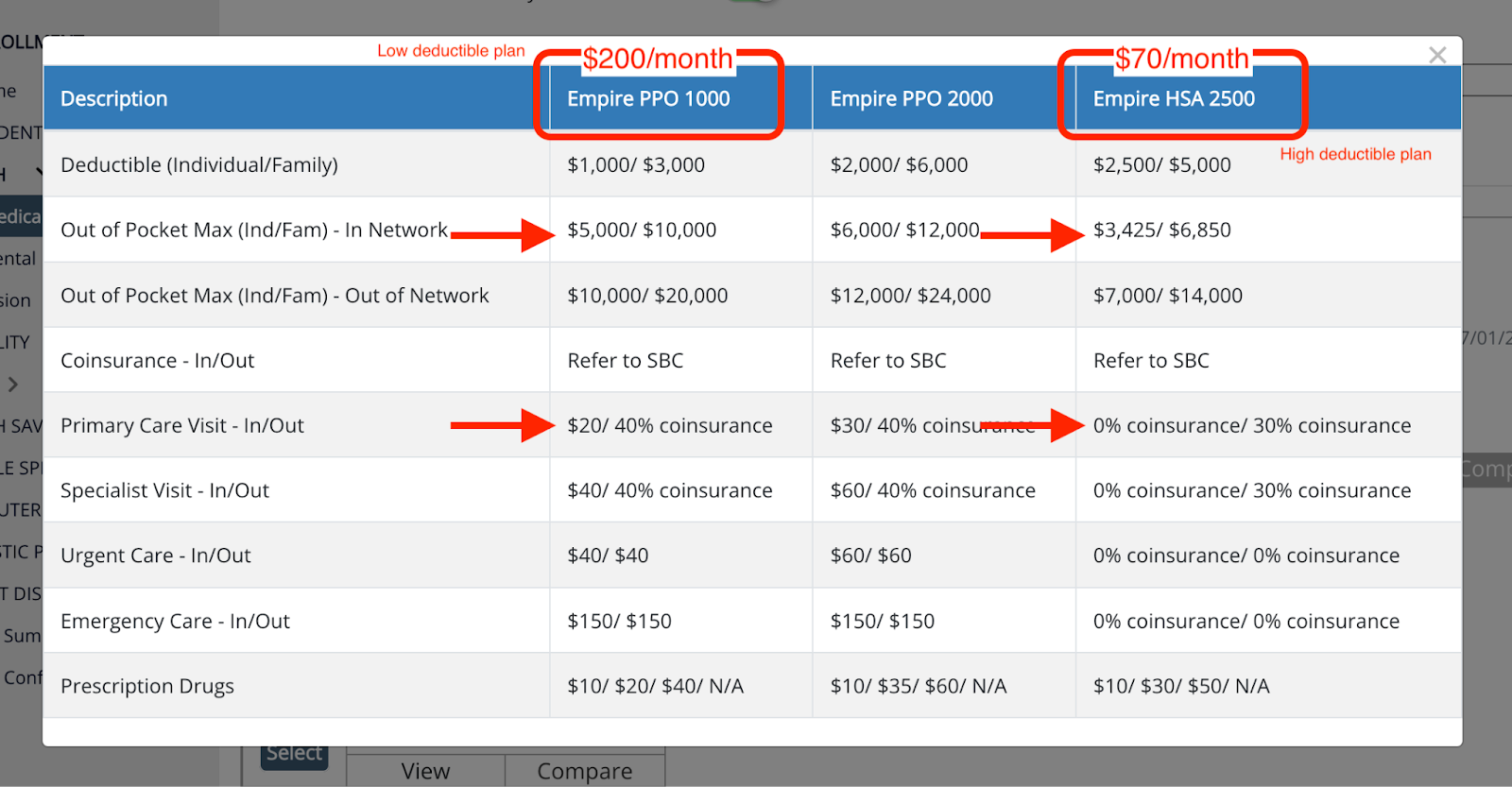

The plan on the far left, “Empire PPO 1000,” is a low-deductible plan that costs $200/month, but with paradoxically higher out-of-pocket maximums ($5,000 single/$10,000 family) than the high-deductible plan’s ($70/month) out-of-pocket maximums ($3,425 single/$6,850 family). Huh?! (Because the nomenclature might be confusing, it’s worth clarifying that—in the plans shown—all three technically operate as PPOs, or preferred provider organizations. It’s a common misconception that high-deductible plans can’t be PPOs, but they aren’t mutually exclusive.)

What gives? Aside from the fact that someone needs a PhD in data science to make sense of this chart, notice the “Primary Care Visit,” “Specialist Visit,” “Urgent Care,” and “Emergency Care” rows. The low-deductible plan has copays—meaning you’ll pay $20 a pop at your primary care doc, $40 at a specialist, $40 for urgent care, etc. for all in-network visits.

And as a fun reminder, those copays don’t count toward the plan’s deductible—but they do count toward your out-of-pocket maximum.

The higher deductible plan in this example? Forget about copays altogether. You’re paying for everything out of pocket until you hit that deductible, honey (after which the listed 0% coinsurance kicks in). Best of luck to you and your wallet! The good news, of course, is that the maximum (again, as long as you stay in-network) you’ll be on the hook for in a given year with that example plan is $3,425 (just you) or $6,850 (family) after you pay your premiums. You’re probably just more likely to hit that deductible than if you’re using a low-deductible plan with copays for routine visits.

For example, if Henah—who has the low-deductible plan—goes to see an in-network primary care physician, she’ll pay a $20 copay. If I go to see a primary care physician with the high-deductible plan, I’ll pay whatever they charge for an office visit (usually in the ballpark of $150).

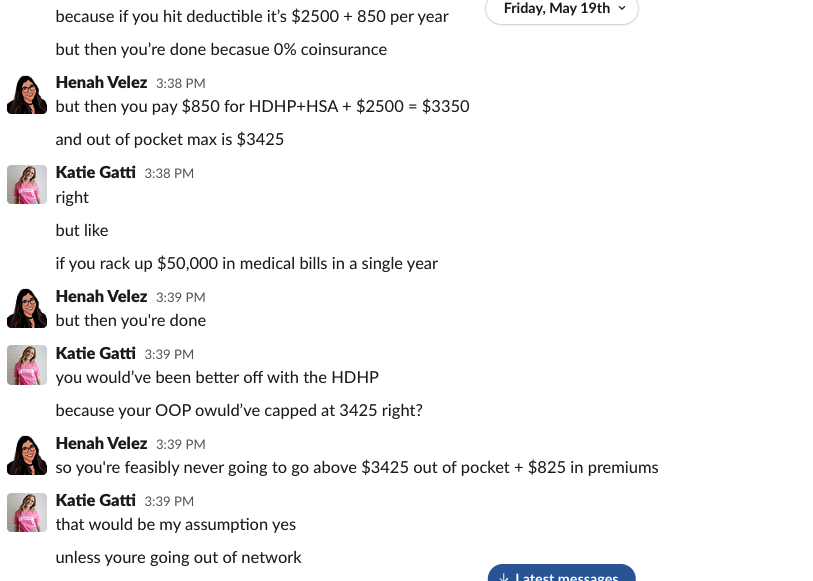

That said, every plan is different, but please enjoy our Slack conversation, which became a flurry of confusion and numbers. Here’s a snippet of our Friday afternoon party in the DMs, where we panic-calculated cost-benefit analysis:

As you can see, the cost calculation in this example is:

-

High-deductible plan for an individual: $70/month + a $3,425 out-of-pocket maximum per year in costs (unless something major happens, you’re probably paying full price for everything out-of-pocket throughout the year) = Between $3,240 and $4,265 projected maximum cost

-

Low-deductible plan for an individual: $200/month + a $5,000 out-of-pocket maximum per year in costs, but with copays that’ll likely cover routine stuff cheaply and a lower deductible ($1,000) you’d need to hit before insurance would begin kicking in and covering 70% of costs until you’ve spent $5,000 total = Between $3,400 and $7,400 projected maximum cost

This example illustrates why people often instruct those who are “young and healthy” or who have very few predictable health-related expenses to go for the higher deductible plan, assuming they won’t need to go to the doctor very often (or at all) and can use the insurance as protection against catastrophic health issues that would run up bills in the tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of dollars. Slowly gestures to the podcast episode about how backward the system is…

I digress.

But that’s not even close to where this analysis ends, because some high-deductible health plans have an ace up their sleeve, in the HSA.

The HSA can be a game-changer, thanks to the tax savings

Because you won’t pay any federal, state, or FICA taxes on payroll contributions to your HSA, you can pretty easily calculate the potential savings you’ll gain (read: money that stays in your pocket instead of being sent off to Uncle Sam for his next highway improvement project) based on how much you earn.

Assuming you’re able to invest the maximum amount in your HSA ($4,300/year for a health plan that covers just you, and $8,550/year for one that covers your entire family in 2025), your potential tax savings are #thicc. In case you’re like, “That seems like a lot of money, dude,” it’s roughly $165 per biweekly paycheck for the “single” coverage and $329 per paycheck for the “family” coverage.

That still may sound like quite a bit, but I think of it like this: Would I rather pay more to an insurance company for a lower deductible, or pay less to them every month and pay myself more (in an HSA)? Depending on the difference in your monthly premiums and the shitty-to-decent gradient of your plan options, it may be pretty close.

Wondering how much you could stand to save in taxes from HSA contributions? I did the hard work for you; I took the marginal tax rate + 7.65% FICA tax to see how much you’d save on your annual tax bill:

-

10% bracket saves $759 on the singles plan, $1,509 on the family plan

-

12% bracket saves $845 on the singles plan, $1,680 on the family plan

-

22% bracket saves $1,275 on the singles plan, $2,535 on the family plan

-

24% bracket saves $1,361 on the singles plan, $2,706 on the family plan

-

32% bracket saves $1,705 on the singles plan, $3,390 on the family plan

-

35% bracket saves $1,834 on the singles plan, $3,647 on the family plan

-

37% bracket saves $1,920 on the singles plan, $3,818 on the family plan

(If you’re not sure which tax bracket your taxable income falls into after accounting for deductions and such, you can check out the 2025 brackets here.)

For example, a family in the 24% bracket who contributes the full $8,550 each year will claw back $2,706 in tax savings, which can directly offset the costs of the insurance. Of course, it also means you have to be able to tie up that much money in your Health Savings Account, which isn’t always realistic.

This also doesn’t take state tax savings into account, which could add even more money back into your pocket; notably, California and New Jersey don’t recognize HSAs as pre-tax vehicles so you won’t save on state taxes in either of these places. Womp womp. Good thing taxes in those states are so low! Oh, wait…

Time to pull it all together for the grand finale.

The tax savings from investing in an HSA can help give the high-deductible plan an edge over the low-deductible plan

Let’s do a quick example to drive home the point and revisit our earlier options.

Things look pretty neck-and-neck, especially when I consider the fact that the low-deductible plan’s copays are likely to make each individual visit to the doctor very affordable (as opposed to being on the hook for $200 for a checkup wherein you accidentally ask one (1) specific question).

-

High-deductible plan has the potential to cost $840 in premiums + $2,500 deductible, or a combined $3,340 (with a worst case scenario of $4,265). We’ll assume it’s probably pretty likely I’ll be on the hook for at least the first $2,500 of my care in a given year.

-

Low-deductible plan has the potential to cost $2,400 in premiums + $1,000 deductible, or a combined $3,400 (with a worst case scenario of $7,400). Thanks to the copays, though, we can assume I probably won’t be on the hook for routine care (beyond $20 or $40 here and there).

But what if I’m in the 24% tax bracket, and I’m able to contribute the full $4,300 to an HSA that just covers me? That contribution gets added to the “assets” side of my balance sheet, increasing my net worth, and I save $1,361 on my federal tax bill, which means I’m “making” an additional $1,361 that year—lowering the net cost of paying for premiums and hitting the deductible in the high-deductible plan to $2,039 (again, we’re not counting the contribution to the HSA as a cost, since you’re keeping that money—it’s not as much a cost as a cash flow consideration).

Now, the difference between our two options is:

-

High-deductible plan’s net cost to hit deductible: $2,039

-

Low-deductible plan’s net cost to hit deductible: $3,400

So we’d save $1,361 over the other plan’s premiums and deductible—is that worth the hassle? Well, remember, it’s not just the up-front savings we’re considering: It’s the fact that these funds in your HSA are invested and will continue to grow tax-free over time, too. (As opposed to the low-deductible plan, where there’s no associated investment vehicle, just potentially lower up-front costs.)

Sometimes I feel like insurance plans are created by a bunch of MBAs in suits throwing darts at a spreadsheet, so it may not always work out this way—but this example is intended to illustrate the framework for determining how much the tax savings may offset the higher deductible of a high-deductible plan, based on your specific plan options.

Put another way: Depending on your tax bracket and single vs. family coverage (assuming you’ll contribute the maximum to your HSA), a high-deductible plan can cost more on the surface than a low-deductible plan, and still end up being net-cheaper.

As complicated as access to healthcare in the US is, if we can view these questions like math problems, it can help us make a decision

The reason choosing a health plan is complicated (aside from the obvious; see previous unintelligible charts) is because we often don’t know what type of medical expenses we’re going to incur ahead of time, making the choice process uncertain and stressful (USA! USA!). But by calculating the “absolutes” of maximum possible costs and factoring in our potential HSA tax savings, we can make a more informed decision.

Or, we could move to Sweden. There’s always Sweden.

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time