What Should You Do with a Lump Sum of Cash You Want to Invest? [2025]

August 30, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

…otherwise known as, the world’s best problem to have.

Maybe you just discovered personal finance education and you’re walking through the world with your eyes wide open for the first time, suddenly painfully aware of the $40,000 sitting stagnant in your savings account earning $40 per year (0.01% interest).

Or maybe you’ve been dabbling in investing for a while, but you recently came into a large sum of money – from an inheritance, a bonus at work, or the sale of a property or asset.

So what do you do?

Do you invest the money all at once, or do you spread out your investments over time?

“Dollar-cost averaging”

“Spreading out the investment contributions over time” is also known as “dollar-cost averaging,” a term that gets its name from the fact that – by making equal contributions to buy the same asset over a predetermined period of time at a regular cadence – you’ll pay the “average” price for the asset over that period of time.

Confusing enough?

Think about it like this: If I have $100 to buy a bunch of apples, and apple prices are super volatile, should I just buy all the apples all at once, or should I buy one apple on the 5th of every month and pay whatever price the apple costs that day?

While this is an imperfect analogy, I think it highlights that our intuition here may be wrong.

You may have thought, “Well, I’d just buy one apple per month. Because what if the prices are too high when I go to buy them all at once? Then I just overpaid for every single apple.”

The difference between our fictitious apple market (should we have used a sexier asset?) and the stock market, though, is that the stock market (S&P 500 specifically) spends about 54.86% of its days “up” from the previous day.

The takeaway? It’s more likely to go up than down, historically speaking, so it’s a safer bet to assume it’ll only be higher in the future when you go to buy again, rather than lower.

Think about it: By distributing a lump sum of money a little bit at a time every month for a predetermined period of time (maybe it’s a year, maybe it’s two years), you’re essentially declaring that you think the market is going to go down. You think the assets you’re buying today will be cheaper in the future, so you’re waiting until the future to buy more.

Investing is, at its core, an optimistic pursuit. We only do it because we have hope that the prices will (generally, over time) rise.

(I’m oversimplifying for the sake of making a point, but wanted to flesh out that reasoning to its logical conclusion for the sake of the post – and because I like the #drama.)

Forced dollar-cost averaging

Some of your investments will be forced into dollar-cost averaging; for example, if you make $5,000 per month and plan to invest $2,000 of it every month, you don’t have the option to invest that annual lump sum of $24,000 upfront on January 1 – you don’t have the money yet.

In that way, every single month when you make your contributions from your income as it’s doled out to you by your kind Corporate Overlord, you’re dollar-cost averaging on accident.

Today, we’re talking about whether or not you should consider artificially applying the same periodic pattern to a big chunk of money you’re sitting on, or toss it all in at once.

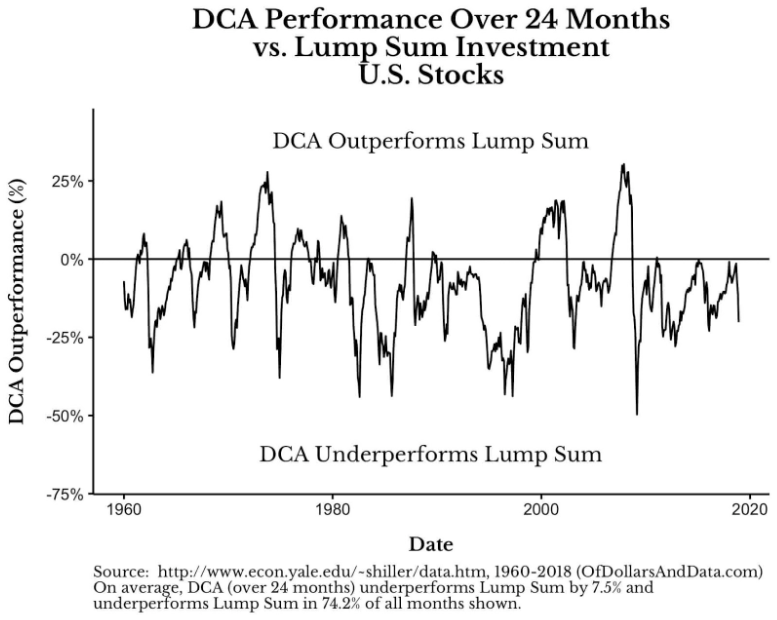

Nick Maggiulli, the COO of a wealth management firm and author of a blog called Of Dollars & Data, demonstrates why lump-sum investing beats dollar-cost averaging, if you have the choice:

You can find his entire analysis here.

Dollar-cost averaging underperforms the lump sum method by 7.5% on average. (He clearly has access to some of the fancier analysis tools that I’m too cheap to pay for, because he was able to do the analysis I was trying to perform by trolling around personal finance subreddits looking for free calculator tools.) Not only that, dollar-cost averaging underperforms lump sum investing in 74% of the months analyzed.

The only times that dollar-cost averaging won out was when the market was actively crashing, as prices were lowering (imagine all of society lost faith in your apples all at once and suddenly the prices plummeted for a few months; over those few months, you would’ve been paying less per apple than normal, until faith was restored in the almighty Honeycrisp and apple markets rebounded).

What this means for you

Majority of the time, you’re going to be better off just investing your lump sum in an investment account all at once. Of course, we never really know when a crash is coming, but if you extrapolate this type of decision over the course of a lifetime, we can imagine it’ll look like this:

Let’s say you come into lump sums of money every 3 years (you lucky dog, you!) for the next 50 years. Let’s say you’re bought into the lump sum methodology, based on my compelling prose coupled with the aforementioned data.

That means you’d have roughly 16.6 opportunities to invest a lump sum.

While (read this in an infomercial voice) past performance is not indicative of future returns, let’s pretend that the findings above can be extrapolated forward: roughly 75% of the time, dollar-cost averaging will underperform your lump sum approach.

But that means 25% of the time, dollar-cost averaging wins.

So that means – in this mathematically sloppy example – you’ll “overpay” for 4 of the 16 lump sums you invest (25%), but you’ll end up ahead and pay less for the other 12.

Or, applied to apples (I regret this metaphor), you’ll overpay for 4 bushels of your apples and “underpay,” or get further ahead, with 12 bushels of them.

But Katie, everyone says the stock market is going to crash soon!

There have been roughly 13 crashes since 1929.

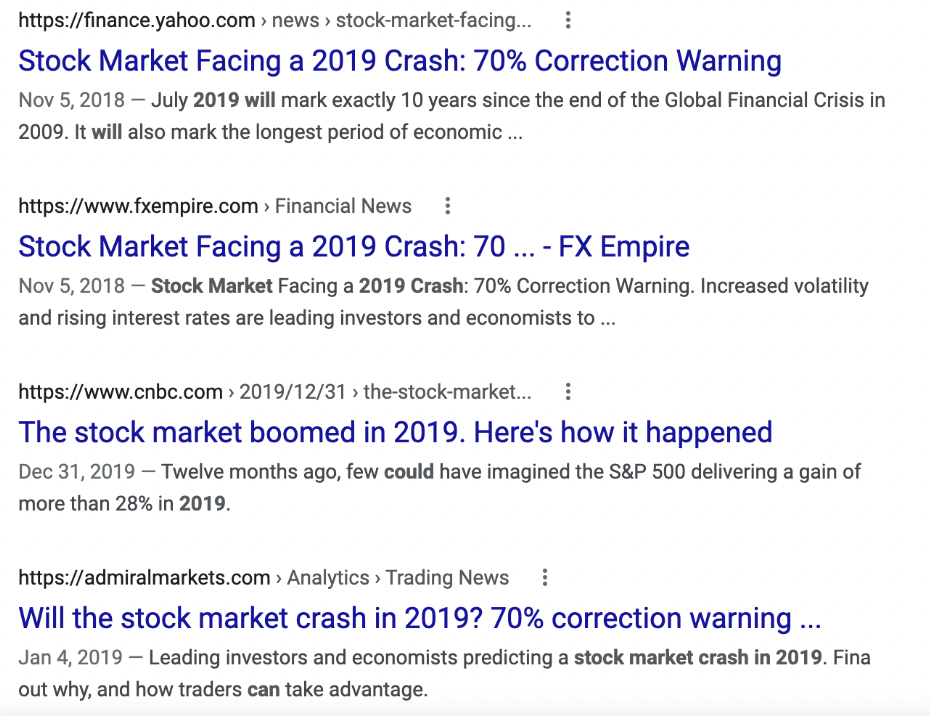

Do you know how many times a crash has been predicted? Just take a peek at quick google search for “stock market crash 2019” (there wasn’t one),

Here’s a sampling of the articles that came up when I googled “stock market crash 2019” (spoiler alert, there was no crash in 2019):

“Leading investors and economists predicting a stock market crash in 2019.”

“70% correction warning.” (Meaning a 70% drop.)

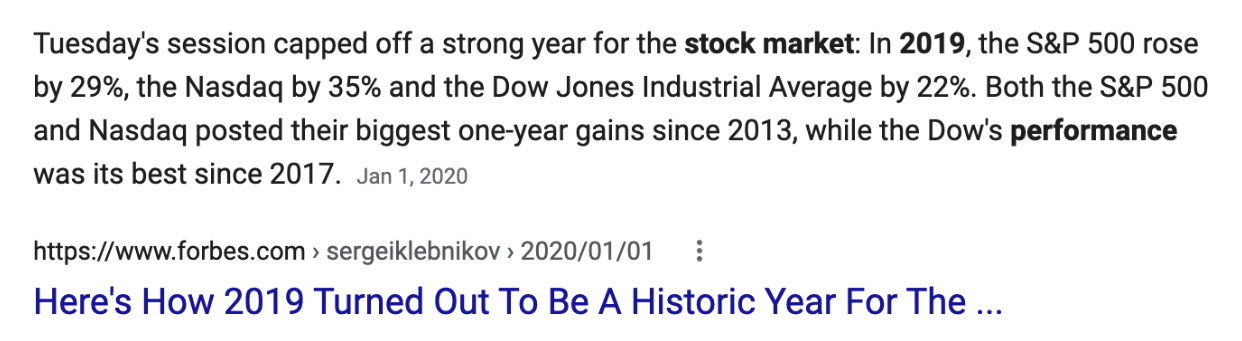

You know what actually happened?

It went up. 29%.

Here’s a blurb from January 1, 2020 (which was, by the way, only three months before an actual crash).

If you’re like, “We’ve meandered so far from the original point. What are we talking about?”

I’ll cut to the chase: Everyone’s always saying a crash is coming. Why? Because eventually, a pundit will be right (it’s just probability; eventually, one will call it correctly), and they’ll make a career-minting press junket news tour out of their (random) accurate prediction.

For example, say you would’ve listened to some headline predicting a 70% crash in 2019, you likely would’ve waited until early 2020 to invest when everyone was feeling optimistic about the market and then promptly experienced the drop in March when things actually did go down, for reasons wholly unrelated to why 2019 doom-and-gloomers were calling it out.

Nobody knows when it’s coming, but you have data on your side to show that prices are more likely to go up than down.

What would I do?

Everyone’s circumstances are different but I’m usually a lump sum girl, through and through. As soon as I get money to invest, I throw it all in there.

And while you can’t exactly put it all in your 401(k), you can fill up other tax-advantaged accounts before jumping to a taxable brokerage account (if you haven’t already). For example, if you have $20,000:

-

$7,000 into a Roth IRA to max it out for the current year, if you haven’t yet

-

$13,000 into a taxable brokerage account

And that’s all she wrote, folks.

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time