Invest Your Energy Like You Do Your Money: Diversify and Don’t Always Expect Success

June 6, 2022

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

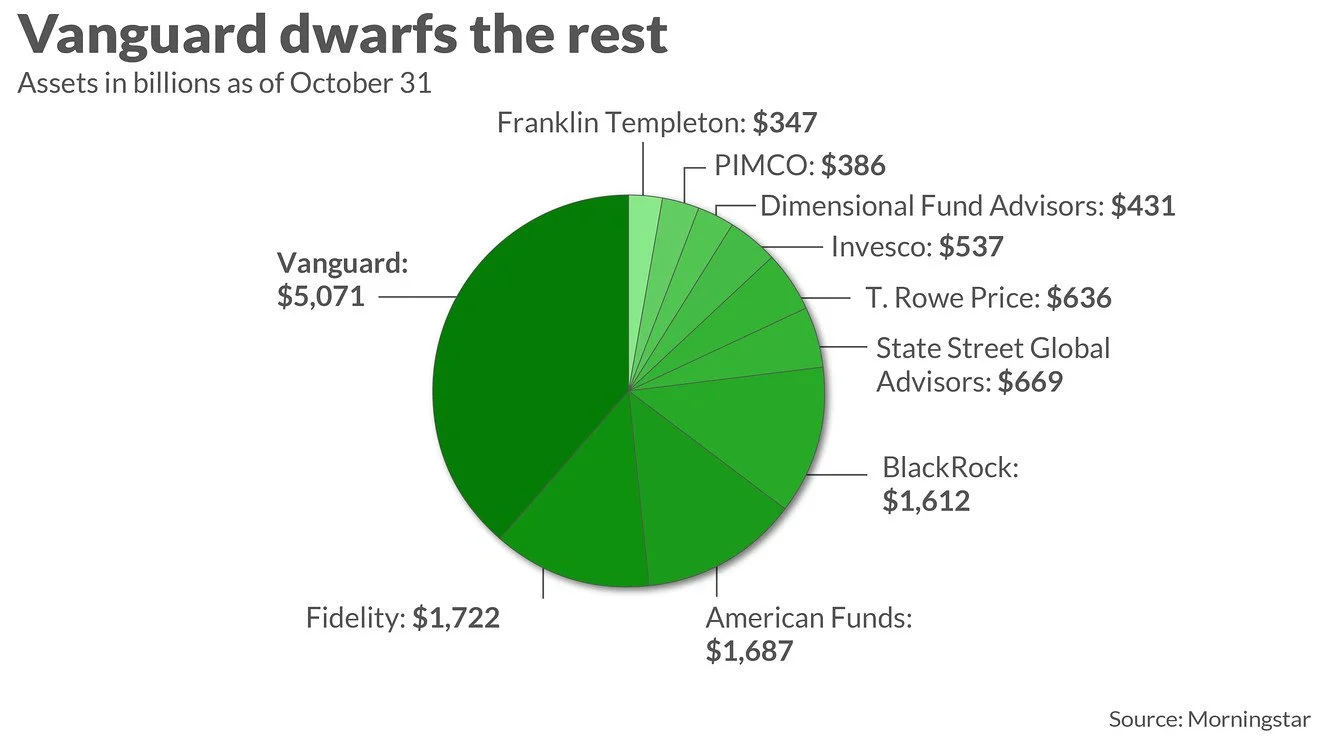

In 2021, Vanguard—the second-largest investment firm in the world, trailing only behind BlackRock—saw inflows of roughly $1B per day. Overall, they’ve got $7.5 trillion under management.

That’s a fancy way of saying that a shit ton of people stick their money in Vanguard.

When we see major firms like this, it’s easy to forget that they were once…not major. Today, Vanguard’s market share is larger than their next-three-largest competitors combined, but it took them 20 years to reach 10% market share. 20 years!

20 years of toiling. 20 years of Jack Bogle going toe-to-toe with Wall Street clowns and being told his idea was stupid and that his business model would never work and fighting for every single dollar under management.

Bogle’s story is interesting in the way that Steve Jobs’s story is interesting—Bogle was booted from his own company and (creatively) came back with a vengeance to change the investing world forever. These are the small plot points in the retellings of their stories: They last for a single sentence, and then are quickly replaced with details of ingenious strategy.

>

“It’s easy to keep going when you know you’re going to win—but when you’re not sure if what you’re doing is going to work, investing thousands of hours over many years is decidedly less easy.”

We forget that the single throwaway sentence of “getting booted from their own company” was not over in a few seconds (as our reading of its retelling is). They didn’t know what was going to happen on the other side of it, and it’s often not a quick, obvious move. (It took Jobs 13 years to make his way back! 13 years ago, I was 14. That seems like an eternity.) It’s easy to keep going when you know you’re going to win—but when you’re not sure if what you’re doing is going to work, investing thousands of hours over many years is decidedly less easy.

What’s impressive to me about Bogle’s story, though, is not that he built the second-largest investment firm in the world and didn’t even seize the opportunity to become disgustingly rich himself (a move that some deem “anti-capitalist”), but that he stuck with it for a grueling decade of net cash outflows every year (meaning…more money was exiting stage right than entering stage left).

When we study these larger-than-life figures, we tend to remember the high points: Dude reads an academic paper about the validity of a fund that tracks an index (instead of actively picking stocks, as was par for the course back then), dude decides to invent said-product and bring it to market, dude becomes legend. End of story.

Or is it?

We often don’t pay much attention to the weeks, months, and years of toiling away and being told “no.” I’m not even talking about the daily work of building Vanguard: I’m talking about all the other false starts Bogle undoubtedly had. The weeks he probably wanted to peace out and do something else. The parts of the story where he expended energy and capital on things that were totally inconsequential to Vanguard’s success.

But that’s the thing: When Bogle was undoubtedly having those human moments, he didn’t know what was going to move things forward and what wasn’t. He didn’t know what was going to provide the return.

That’s because the plot points that don’t drive the narrative forward are usually omitted as the legend becomes streamlined and crystallized in the collective memory—it serves to create a world wherein we have this myopic, predictable understanding of how our renegade idols darted about the world, saw the clear path forward and did what nobody else dared to do. We oversimplify—and in the process, we forget that the mundane consistency of our day-to-day lives is often slowly weaving together our own narrative that we’ll someday reflect on and realize, “Oh, that’s how I got here.”

>

“The plot points that don’t drive the narrative forward are usually omitted as the legend becomes streamlined and crystallized in the collective memory.”

And we, too, will omit and gloss over the parts that don’t drive our personal narrative forward.

I noticed recently as I did a string of “Money with Katie” interviews that I was—unintentionally—creating this very sensible tale about how I got to where I am now. It’s the more exciting, edited version of the story, wherein I realized one random Tuesday that I wanted to change my life, and—in no short order—started a personal finance blog, grew that blog, and sold that blog to a larger organization, cashing in on a dream job and riches I never imagined when I graduated from college five years earlier with a degree in PR.

If only it were that simple, right?

If only it were that clear while we’re in it.

That’s the “podcast version” of the Money with Katie story. The Guy Raz “How I Built This” narrative.

Here’s what that story does not include:

-

The phase between Corporate Barbie and Money with Katie where I thought I was going to become a full-time fitness instructor, so I went through hundreds of hours of training and taught hundreds of fitness classes. That meant approximately 200 mornings of waking up at 4:30 AM to teach a 45-minute class and 200 more evenings of rushing through traffic to teach a 5:30 PM class. Conservatively, I spent 1,000 hours learning how to be an instructor (and being an instructor). One-thousand hours!

-

Not one, but two failed personal finance consulting businesses I ran (I started one, and joined a friend for the second) where the rates were an embarrassingly low sum, for hundreds (yes, hundreds) of one-on-one coaching sessions.

-

The countless amount of time I spent applying for jobs in 2020 when I was terrified I was going to lose mine, of which only two ever netted employment (my applications surely exceeded 50 per week at their peak).

-

The five years I spent writing on my old blog that never made a single dollar or gained even a small semblance of the audience that Money with Katie has. Five years! That’s more than twice as long as I’ve been writing Money with Katie.

I realize I’m walking a thin line between the point I’m trying to make and the irritating, overdone “It TaKeS a LoT oF hArD wOrK” trope, so I’ll clarify where I’m going with this:

So much (so much) of my time and effort from (a) the original realization I wanted to change my life and (b) where I am now was effectively wasted. “Wasted” in the sense that it didn’t culminate in anything impressive or noteworthy or lucrative, and also in the sense that I spent most of the weekends during those years very drunk. Coincidence? Probably not. #PartyWithKatie

And while I could sit here and make the case that each experience ended up netting something useful for my current endeavor (fitness = leadership and crowd presence and confidence, personal finance consulting = a rich repertoire of knowledge about what young women care about), that’d feel like a stretch.

>

“We do others (and ourselves, frankly) a disservice when we refine the edges too much.”

But when I tell the story retroactively, I can neatly stitch the plot points together and narrate how they build so perfectly to create this obvious path to Money with Katie, but that’s only possible in retrospect. I had no idea what the fuck I was doing as I was doing it, and I’d venture a guess that most people who’ve built something they’re proud of would probably say the same.

Unfortunately, we do others (and ourselves, frankly) a disservice when we refine the edges too much. We lull one another into this false state of assurance that when you’re doing the thing you’re supposed to be doing, you’ll know it—and you’ll know where to go, what to do, and how to do it. But that’s not how life actually works.

The reality of life is that it’s a little bit like buying an index fund (sorry, this is Money with Katie after all, a money metaphor had to be made). You’ll expend capital (read: energy) toward 1,000 different stocks (endeavors), and 912 of them will be total shit with low or no yield. 84 of them will do a little something, and the remaining four will be so successfully glorious that you’ll wonder how you didn’t see it in hindsight—it was so obvious, huh? Yeah. Not so much.

Everyone swears in hindsight they could see the 2008 global financial crisis coming. Or that the 2020 market rally was predictable from all the stimulus.

But if that many people really knew, there wouldn’t be a mere handful of people who became very wealthy from shorting the economy in 2008 (and even those clairvoyants haven’t done so well since then).

It’s not that I think people are liars—just that we fool ourselves into thinking the “signs were there,” when in reality, we can only see the story clearly once it’s already happened. We forget about all the signs that pointed in the other direction and only remember the details that confirm the reality of what actually happened.

Our memories of our own lives are similar, and the way we memorialize epic people is, too.

But that’s a mistake, because oftentimes the largest ROI comes from the work you don’t see. Day-to-day life and the thousands of small decisions we make every single day compound over time to slowly shape the directions our lives take. We can look back and identify those sliding-door moments, but while we’re in them, we have no idea they’re shaping our path.

My favorite example of this in recent memory? After a few songs became major hits in 2019, Lizzo was asked in an interview what it felt like to be an “overnight success.” She was like, “Overnight success? Dude, I’ve been doing this for eight years.”

>

“Oftentimes the largest ROI comes from the work you don’t see.”

ROI comes from the work you don’t see. “Gradually, then suddenly.”

A lot of our work (and capital) will be wasted. A lot of it won’t return anything useful or productive or valuable. We must become volume shooters in life and investing—invest our personal energy and capital early and often in a diverse set of opportunities to increase our chances of high returns. This probably looks like saying “yes” to things we aren’t sure about, investing more than we think we need to, and not expecting phenomenal results most of the time.

And when we get those high returns, we can look back and say, “I knew it.”

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time