3 Tips for Successful Investors in Down Markets: Ignore “Buy and Hold” at Your Own Peril

April 11, 2022

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

That title feels ominous, huh?

The other day, I was mulling over the Traditional vs. Roth debate (#JustKatieThings) again because I was running some projections that showed someone who invested really wisely in a Roth IRA at age 22 could easily 15x their money over 40 years, making the tax liability they originally paid minuscule (though I still ended up coming back to my original thesis: that it only matters if they plan to withdraw all their gains at once, which practically nobody does).

Anyway, as I was playing with different returns to figure out how likely it would be that someone who starts investing in their twenties would be destined to end up with millions of dollars, I started to wonder something:

While the market returns about 10% per year on average, is it reasonable to expect that your average investor is going to get 10% per year?

While I’ve written in the past about how it’s possible the average-10%-per-year estimate (pulled from a 100-year history of the market that states the Total Stock Market as measured by proxy by the S&P 500 returns 10% on average per year, before inflation) might not happen in the future because assets are relatively overpriced right now, I ended up settling on a much less sinister explanation for why the average investor shouldn’t bank on getting 10% average returns:

Average investors have a really hard time ignoring their own psychology and buying and holding for the long-term.

Dalbar, Inc., a company that studies investor behavior and analyzes investor market returns (sounds fancy), found that average investors earn below-average returns.

How below average?

Well, for the years between 1999 and 2019, the S&P 500 averaged 6.06% per year (mostly dragged down by abysmal 2000-2009 returns after the DotCom crash and subsequent financial crisis in 2008).

The average equity investor didn’t get 6.06%, though—they only earned an annualized average return of 4.25%. Yikes. That changes our projections for the future quite dramatically, no?

In that sense, it means that your ability to get 10% annualized returns over the long run might have less to do with the stock market itself than it does your own behavior.

Because I am—at my core—a neurotic over-preparer, I use 7% average returns + 3% inflation for an average 4% annualized return in the Financial Independence Planner that I use for all my projections in blog posts. I used to feel like I was being way too pessimistic, but now I’m feeling like maybe that was a gut instinct that served me well. I don’t know about you, but I’d rather assume I’m going to do worse than average so I’m pleasantly surprised by over-performance.

Since 1984, 70% of underperformance occurred during only 10 key periods in which investors withdrew their investments during periods of market crises

Translation from data speak: The vast majority of underperformance happened during a handful of market events in which people freaked out and pulled their money out because the market was crashing.

Even more surprising, 80% of time, if an investor had simply held onto their money and done nothing, they would’ve gotten better results a year later—and remember, that doesn’t even assume that they’re holding the S&P 500 or another large cap index fund, just that if they would’ve held whatever they were holding instead of selling it, they would’ve been better off a year later.

The scariest numbers I saw in the report? The 30-year return of the S&P 500 (the benchmark this report is using, by the way; I’ll always advocate for diversifying beyond it and including things like Small Cap Value and International funds in your portfolio, but I digress) was 9.96% (where that “10%” number comes from), while the average investor only got 5.04%.

Yikes again.

That halves the average that most of us personal finance fanatics use in our forward-looking projections (and maybe means that my “pessimistic” Financial Independence Planner is more accurate than I thought).

How to not lose your money (or your mind) during downturns

All right, so by now, we probably understand that two things are true:

(1) Owning a diversified set of index funds and (2) holding them for the long-term is the best way to build wealth without making large, risky bets.

Here’s the Money with Katie guide to not blowing your own lead and selling equities when shit hits the fan (and yes, it’s simple in nature—infomercial voice—just three easy steps).

1. Build your portfolio the right way in the first place.

We’ve seen a lot of investor euphoria since April 2020 when the market began its inexplicable (well, not totally inexplicable) climb upward, and it became easy to forget that stocks don’t always go up.

People were taking on more risk (assuming the reward was guaranteed) and keeping super lean cash reserves.

In some cases, that’s OK—if you’ve got multiple sources of income, low expenses, and a small likelihood for emergencies (in other words, you’re not a homeowner or a parent), you probably can get away with keeping a pretty lean safety net.

I think there’s something to be said for identifying the real amount you need in an emergency fund (because sometimes cash-creep happens and you end up with way too much sitting on the sidelines), and investor euphoria can provide the greedy incentive for reexamining that…

But investing a down payment that you need in 90 days?

Putting your entire emergency fund into VTSAX?

That’s a recipe for, “Oh, shit, the market is dipping, I need to get that money out now before it dips anymore because I need that money soon.”

It stands to reason that your likelihood of pulling money out at the wrong time increases when you invest money that you shouldn’t be.

Beyond keeping the “right” amount of cash on the sidelines to bolster your needs during downturns, it also stands to reason that investing in a diversified mix of index ETFs (as opposed to just one, or a sampling of ETFs that have high correlation) will help buoy your portfolio in the down times and limit the extent to which you feel like you have to make changes in the moment.

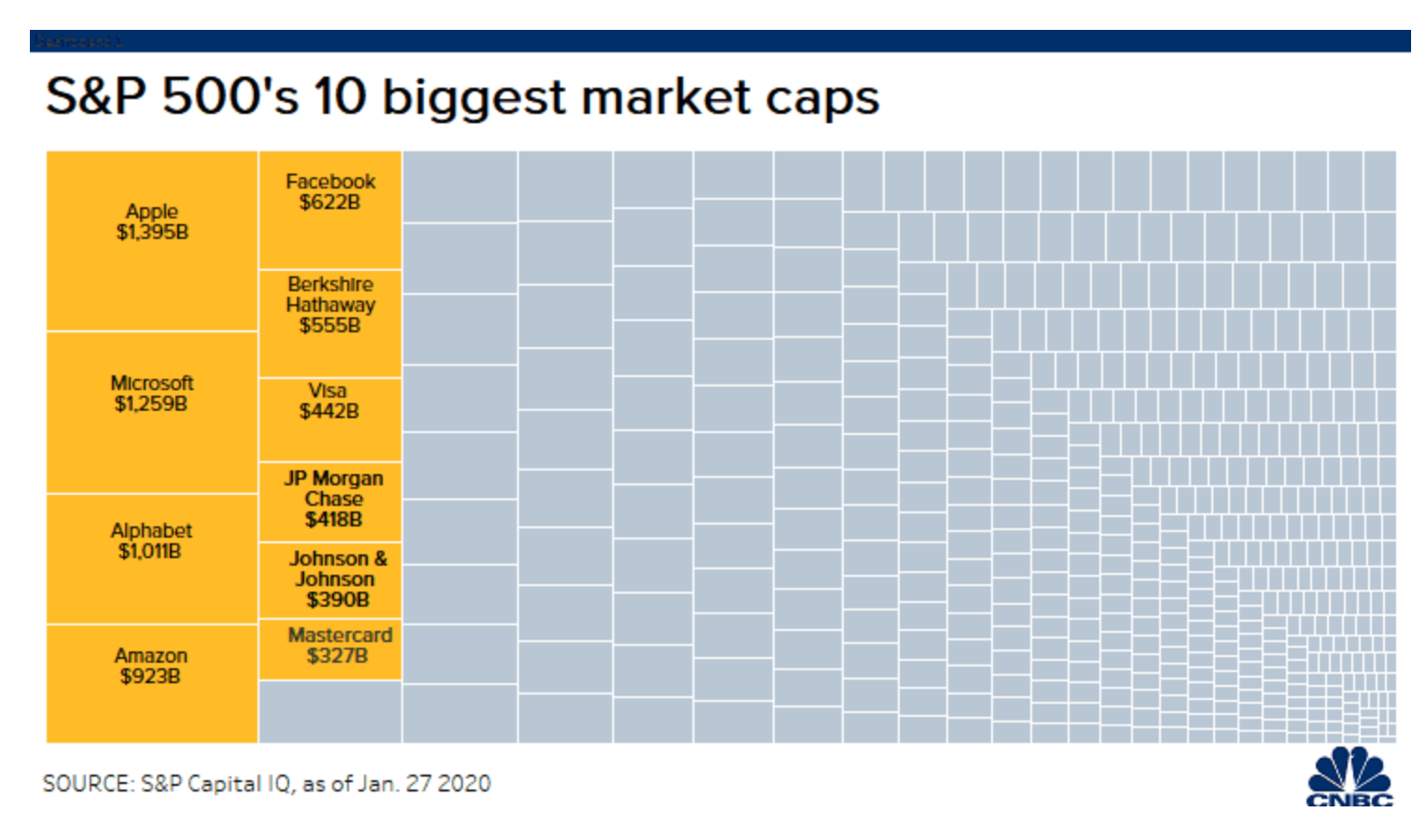

For example, when Tech stocks get crushed ($FB dropping 26% in a single day after a poor earnings report), it disproportionally impacts Large Cap Growth ETFs like those that track the S&P 500 (Vanguard’s version is called VOO and it’s a favorite on Personal Finance Instagram). Check out the visualization of how much of the S&P 500 is $FB:

Source: CNBC

That’s normally a good thing, since these tech companies are profit machines via monetization of our own precious attention (yay!), but it also illustrates how the fate of just a few companies (that are typically impacted by the same market forces, regulation changes, and sentiment) more or less dictates the fate of the entire fund.

If you only own the S&P 500 (or the S&P 500 + Total Stock Market) and Large Cap starts getting pounded, you’re going to feel it deeply—and likely feel more compelled during the downturn to diversify or sell.

But just like it’s not advantageous to try picking at a zit once it’s already inflamed and irritated, you’re better off proactively diversifying and making sure your portfolio is benefited by low-ish correlation between the things you own.

And that’s what this is about: Navigating your own psychology and increasing the chances you’ll hang in there.

Now that we’ve gotten #proactiv (the zit puns abound!), let’s talk about two psychological strategies.

2. Remember you still own the same number of shares.

This is something that helped me a lot during the January 2022 correction.

Think about it this way: It’s pretty disheartening to conceptualize tossing money into a bucket and—over time—losing dollars in the bucket. That’s scary, and it’s activates that funky human behavioral reaction of loss aversion. We feel like we’re losing money and we want to stop the pain.

It suddenly feels riskier.

But if you imagine you’re exchanging that money for a piece of a company (share)?

If you remember that you still own the same number of shares and that the number in your brokerage account with the dollar-sign next to it is just the quick conversion of those shares into what they’re worth right this second, it’s easier to hang on and alleviate the feeling that you’re losing anything.

When prices start falling, pay attention to your number of shares instead, and remind yourself that that number is the same.

Focus on getting more of those shares while they’re priced lower than before, as the number of shares is the only metric by which you can fairly judge your own progress (since the market being really up or down could give a false sense of progress or failure).

3. Embrace boredom and inaction.

This advice is cliché, but popular for good reason.

For whatever reason, it becomes more tempting to interfere and get creative when markets are going down. We feel like we must be able to “effort” our way through the bloodbath; to identify the trends and get ahead of them.

This is a classic investor folly, to the point that it’s practically a trope.

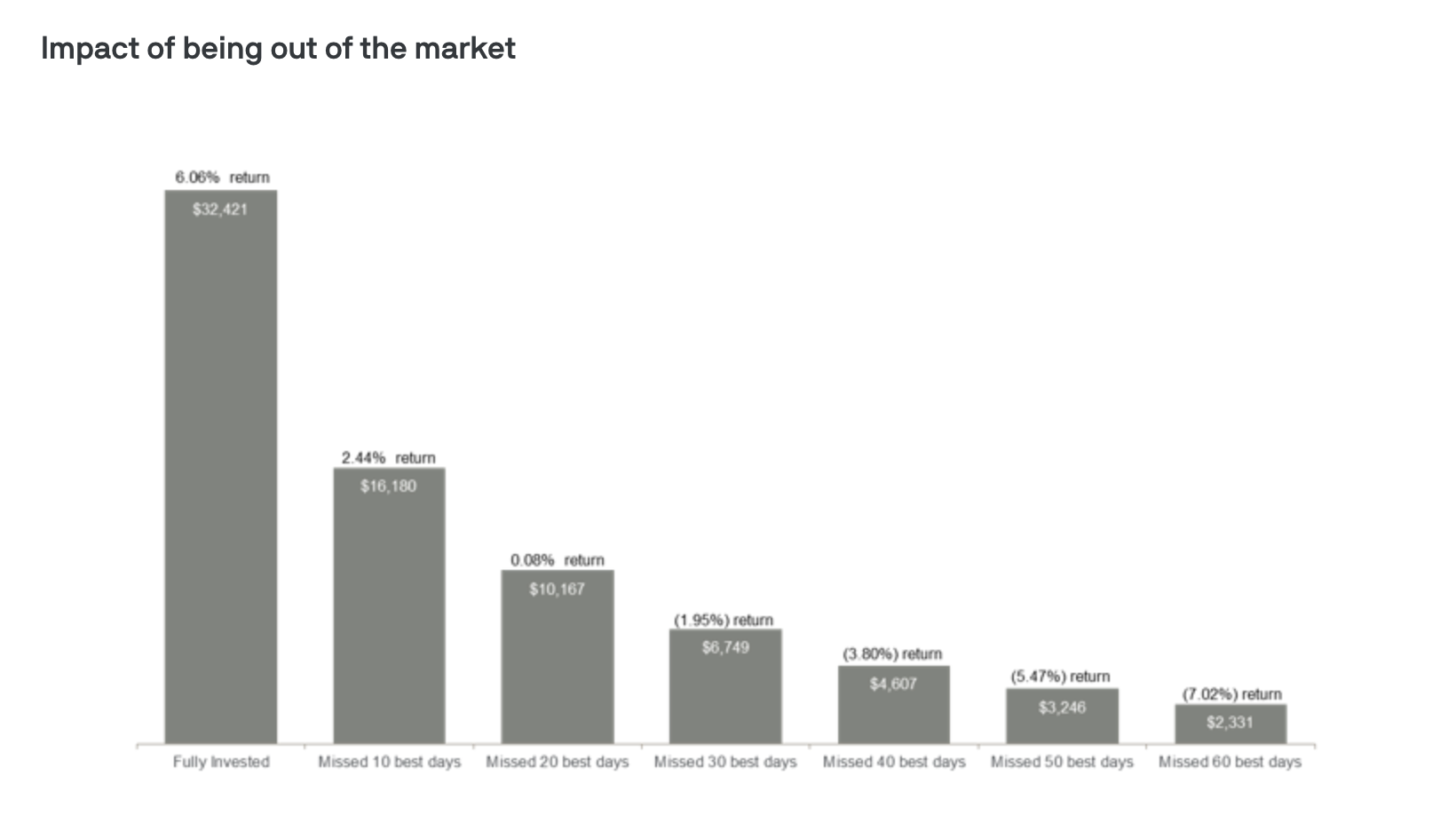

But the effects of missing the best days in the market are well-documented. Look at this #graph (please hum Nickelback softly to yourself) from J.P. Morgan Asset Management Analysis that demonstrates the absolute haircut you would’ve taken if you missed only the 10 best days in the market (assumes you own S&P 500) between 2000 and 2020:

Source: JP Morgan

And if you’re like, “Yeah, but shouldn’t it be relatively easy to not miss the best days? If I’m pulling my shit out when it’s tanking, how likely is it that I’d quickly miss a best day?”

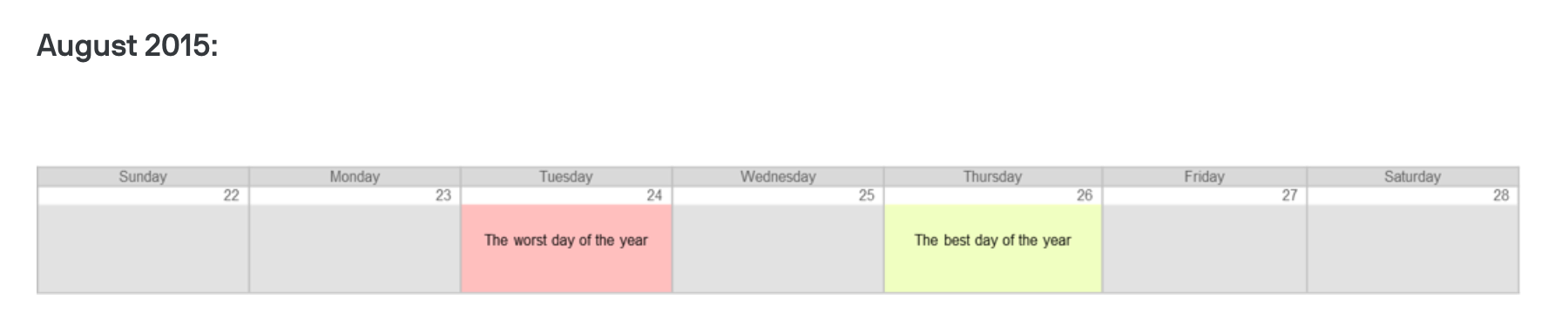

Turns out, it’s not easy at all: 6 of the 7 best days occurred after the worst day. 7 of the 10 worst days were followed the NEXT DAY by either top 10 returns over the 20 years OR top 10 returns for their respective years.

This picture is worth a thousand words:

In conclusion

To try to limit your chances of getting nervous and blowing it, try:

-

Having the proper amount of cash set aside in the first place for your personal comfort and expected purchases, and diversify your invested funds proactively.

-

Remind yourself with excessive fervor that you still own the same number of shares when things are down. In fact, if you need to stop tracking your net worth in “dollars” and start tracking in “shares owned,” try it.

-

Tattoo these charts about missing the 10 best days in the market to the inside of your arm and reference them frequently.

Realistically, when we project 10% average returns with 3% inflation for our portfolios (or 7%, if you’re trying to control for inflation, though you’ll technically end up with slightly different outcomes doing it that way), we have to remember that it’s not outrageous to claim that our behavior determines the likelihood that we’ll get that return more than the market itself does.

So if you want to use 10% returns, remember: You sacrifice your right to those the moment you start trying to hop in and out. If that’s the strategy, create future projections using average 5% returns instead, as that’s what the data tells us is more likely (and—bonus!—it’ll hopefully serve as a deterrent for trying to time the market).

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time