Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

School is back in session in the Sacramento suburb where my husband and I bring down the property values by being, to my knowledge, the only renters (gasp!). This means I watched the early-morning traffic reprieve we enjoyed all summer come to an end during my 7 AM stroll last week.

As I passed the four-block-long procession of cars inching toward the high school, I chuckled to myself. There was an uncanny number of barely distinguishable white, luxury SUVs in a row, silently performing a Roseville Automall roll call: Mercedes, Mercedes, BMW, Tesla, Audi, Mercedes, Cadillac, Audi. The scene tickled my sense of comedic absurdity. I imagined trying to explain to a Victorian child why everyone in this subdivision owned vague variations of the same vehicle.

Then a horrifying realization befell me: I, too, have one of these barely distinguishable white, luxury SUVs. The call is coming from inside the garage.

>

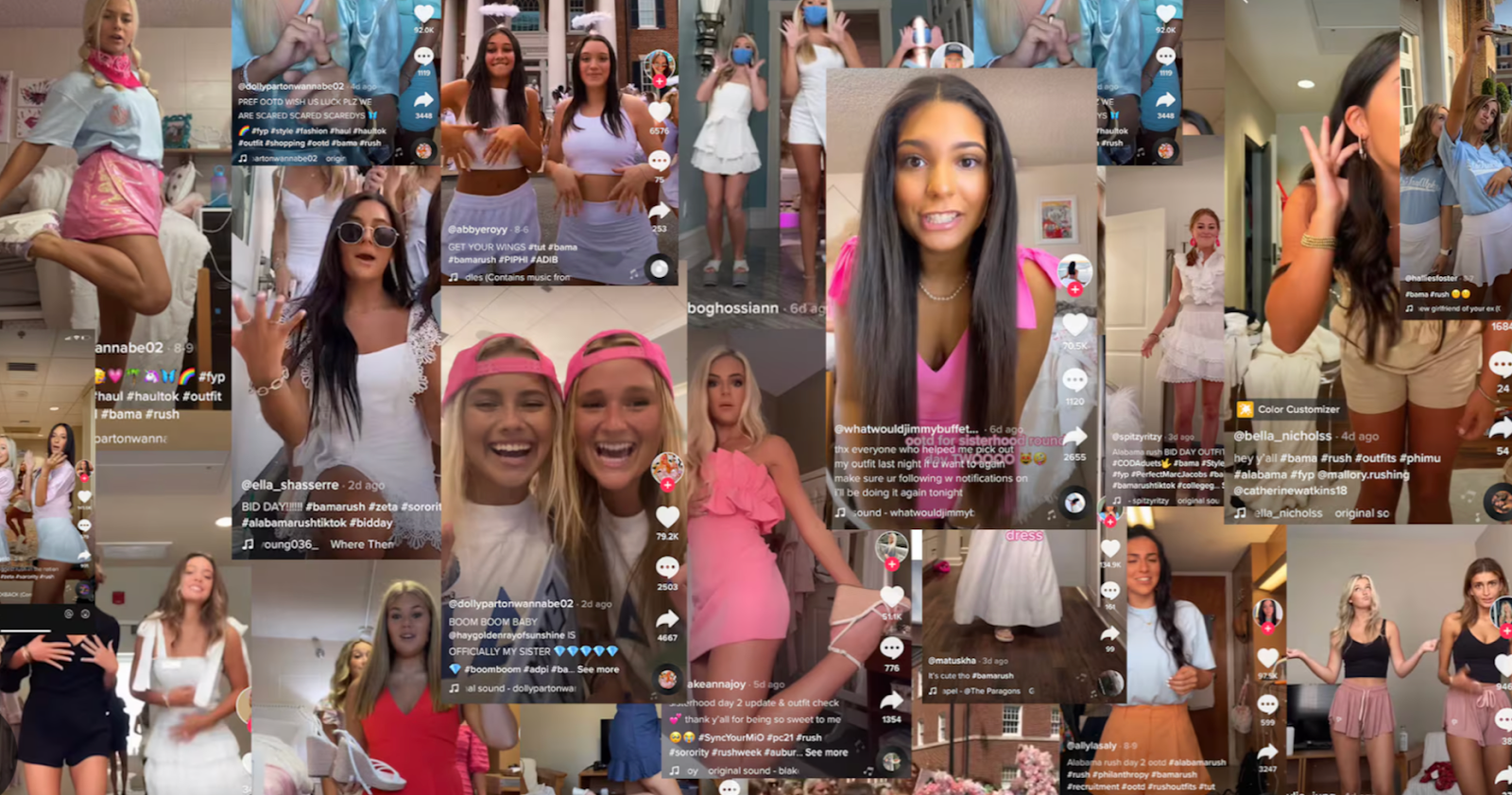

“You don’t have to watch many of these RushTok videos before you notice: They all look the same. ”

I realized I’ve been here before: This parade of undifferentiated automotive wealth reminded me of my experience rushing (and joining) a sorority. The scent of unbridled striving and Miss Dior Eau de Parfum is in the air: Last Saturday, the potential new members at my alma mater, the University of Alabama, received their bids, and the whole process leading up to this climax was captured on TikTok via a three-year-old trend called “RushTok.” (If you’re unfamiliar, the hashtag #BamaRush has accumulated 3.3 billion views on the platform as of 2023.)

Ostensibly, the entire point of going through sorority recruitment—both as a sorority attempting to attract new members, and a new member trying to obtain a bid—is differentiation. Otherwise, why would there be 24 options to choose from? The week is discussed as though there’s a sorting hat magic that occurs (“trust the process” is a commonly wielded phrase) that shuffles you, Plinko-style, to your one, true home.

But you don’t have to watch many of these RushTok videos before you notice: They all look the same.

Credit: Business of Fashion

The phenomenon responsible for this sea of sameness—whether we’re talking about BMW X5s or Tridelts—is called “mimetic desire,” a theory that says our experience of wanting is not innate or individual, but social. We usually want things because other people want them.

The vast majority of women in these Bama RushTok videos are white. The same brands are mentioned on a loop (“Gold Hinge,” “Lulu,” “Amazon,” “Dior,” and Lord, if I had a dollar for every time I heard “bracelets are enewton,” I wouldn’t need sponsors for the rest of the year). All the hopefuls open with the same melodic, syrupy “hey, y’all” before launching into the details of their outfit; most of the active members in the dancing-in-front-of-our-mansion videos are wearing some variation of the theme “spandex and neon.” Even the girls from Ohio somehow acquire Southern accents before the week is over. The entire ordeal is positioned as a series of tough choices requiring supernatural levels of discernment, so the fact that it’s all mostly indistinguishable makes it feel like satire.

When I went through rush more than 10 years ago, the echolocation cultural signal that was beamed out from sorority row in Tuscaloosa 559 miles from my home in Kentucky was strong enough that I showed up on campus with a plastic tub full of the season’s hottest print (chevron) and accessories (statement necklaces). For the curious, I talked at length about my experience here.

Just a couple of gals with unique senses of personal style!

There are shades of gray, of course; some houses had reputations for being “partiers” (a silly distinction, seeing as partying was a university-sanctioned activity for every house) or “Christians” (also silly, as we were in Alabama, the most religious state in the US). But for the most part, the barriers between houses were imaginary—because the actual differentiation happens before rush even starts.

The stratification that occurs in the sorting process just serves to assess how well you embody this particular brand of sameness—and that embodiment, of course, costs money. The clothes, the jewelry, the hair, the makeup…assuming you’ve got the grades and recommendation letters to play ball, most of your fate is determined by your ability to make the correct consumer “choices” to signal that you’re a gal who gets it (choices in scare quotes, see also: the abundance of chevron).

Credit: AL.com In this photo of three women, I count two Lululemon Align tank tops. In the interest of transparency: I currently own this shirt in eight colors. In fact, I’m wearing one right now.

As my suburb’s vehicle of choice proves, this phenomenon is by no means contained to Alabama’s campus—it’s just that #RushTok creates the perfect social experiment for examining it, as the implicit is readily made explicit. It’s the most literal manifestation of the reality that our (very human) desire for belonging is often expressed in material terms. (For the sake of this metaphor, I’m setting aside the obvious fact that membership literally costs money.) Through the lens of mimetic desire, “personal preference” is a half-baked explanation for why you like what you like, because it fails to examine why those things became your preferences in the first place.

As is true of any institution or tradition meant to confer status or prestige (Ivy League schools, top-tier investment banks, gated communities, hot vacation spots), the path of least resistance is paying to assimilate; to perform your belonging by adorning your person with the right stuff. If “assimilation” sounds derogatory, consider the extent to which an obsession with individuality and uniqueness is a pretty American ideal in the first place.

Maybe that’s the real reason my initial amusement at the Mercedes motorcade got me thinking about rush—because I find myself observing from afar with a mix of fascination, amusement, and ultimately, uncomfortable recognition. From the outside looking in, their choices seem so predictable. “Of course you’re wearing LoveShackFancy,” I want to shout at Mary Claire through the screen. “Florals for rush? Groundbreaking.” The clips induce a wince of familiarity as I recall scouring active members’ Facebook pages to gauge how I should present myself to look as though I, too, spent my summers at Rosemary Beach. (Another memory: Being pissed at my mom for saying no to my requests for Lilly Pulitzer, the LoveShackFancy of 2013.)

When I see these 18-year-olds enthusiastically yeet themselves down the same well-worn path, I like to imagine I wouldn’t have rush-shipped a counterfeit Hermès bangle from Guangzhou before departing the greater Cincinnati tristate area for the Deep South—but I poke fun at this because, obviously, I am this. Present-tense. White SUV in the garage, Lululemon tank tops in the closet.

Walking home that morning, I reflected on my mythologizing of the Porsche Macan before I bought one. It was obvious to me when I wrote about it last summer that it had come to symbolize something else, but at the time, I didn’t interrogate what imbued the car with its symbolism in the first place.

After moving to Dallas in 2017, there was one woman in my orbit who fascinated me. She was a successful entrepreneur, having left a powerful job at Pepsi to become a private chef and yoga instructor. It’s worth noting she was also conventionally beautiful and charismatic. I’ll let you guess what she drove.

>

“What I perceived as a love of fashion growing up was not an appreciation for the art of dressing, but a passion for fitting in.”

In the US, we’re taught to think about consumer choice as a way to express our agency and identity. To admit that most of the things I like, desire, and buy are probably just the things that the women I admire like, desire, and buy is a recognition that most of my consumer choices are bids for belonging, not self-expression. What I perceived as a love of fashion growing up was not an appreciation for the art of dressing, but a passion for fitting in.

These choices are not necessarily detrimental—sometimes it’s fun to see something, want it, and buy it. You have to wear something; who cares if the reason you like a dress is because it subconsciously reminds you of someone you admire? In some ways, it’s the most natural thing in the world—still, it’d be disingenuous to assert that these purchases are totally devoid of meaning.

The great paradox is this: When we understand our consumer choices not as an expression of our uniqueness, but instead as a reflection of our demonstrated social preferences and aspirations, we end up learning even more about ourselves—and who we are trying to become. The bigger question is: What will it cost you?

August 19, 2024

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time