Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

“Even with men doing more parenting than before, the majority of women are still left facing the well-rehearsed motherhood-versus-career dichotomy. But it’s not a dichotomy; it’s a socially organized choice masquerading as a natural one.”—Laura Kipnis

A few weeks ago, I betrayed my better judgment and found myself wandering innocently into the comments section of a Wall Street Journal article about the wage gap. This particular article posited that the wage gap opens relatively early in a career, examining salaries for male and female students only a couple of years after they crossed the graduation stage. Its findings will be unsurprising to most young women working in male-dominated fields: Even after only a year (or three) in the workforce, there’s an observable and consistent gap in pay.

Per the Wall Street Journal, the data studied 1.7 million graduates from the classes of 2015 and 2016 and found median pay for men “exceeded that for women three years after graduation in nearly 75% of roughly 11,300 undergraduate and graduate degree programs at some 2,000 universities.” They found that—in roughly half the programs studied—the men’s earnings were outpacing women’s by around 10% or more after three years in the workforce.

The article’s colorful comments section (1,400 strong) was populated most emphatically by Pauls, Kevins, and Tonys offering up explanations for why women are paid less than men; note that the split between those who were (a) refuting that the wage gap exists and those who were (b) justifying its existence was roughly 50/50, so rage-scroll at your own risk.

My favorite commenter, though, had to be Stephan, who—in an effort to dismiss the statistical significance of the article at hand—inadvertently hit the nail on the head:

“My experience as an engineering manager is that men worked longer hours. I managed a group of 9 men and 8 women. The women had kids to deal with. Their husbands/boyfriends didn’t do the kid stuff.”

>

“Men’s earnings were outpacing women’s by around 10% or more after three years in the workforce.”

Hm.

Another commenter named Julie put the entire team on her back with the most incredible refuting one-liner of all time:

“Odd, the inequity in parenting.”

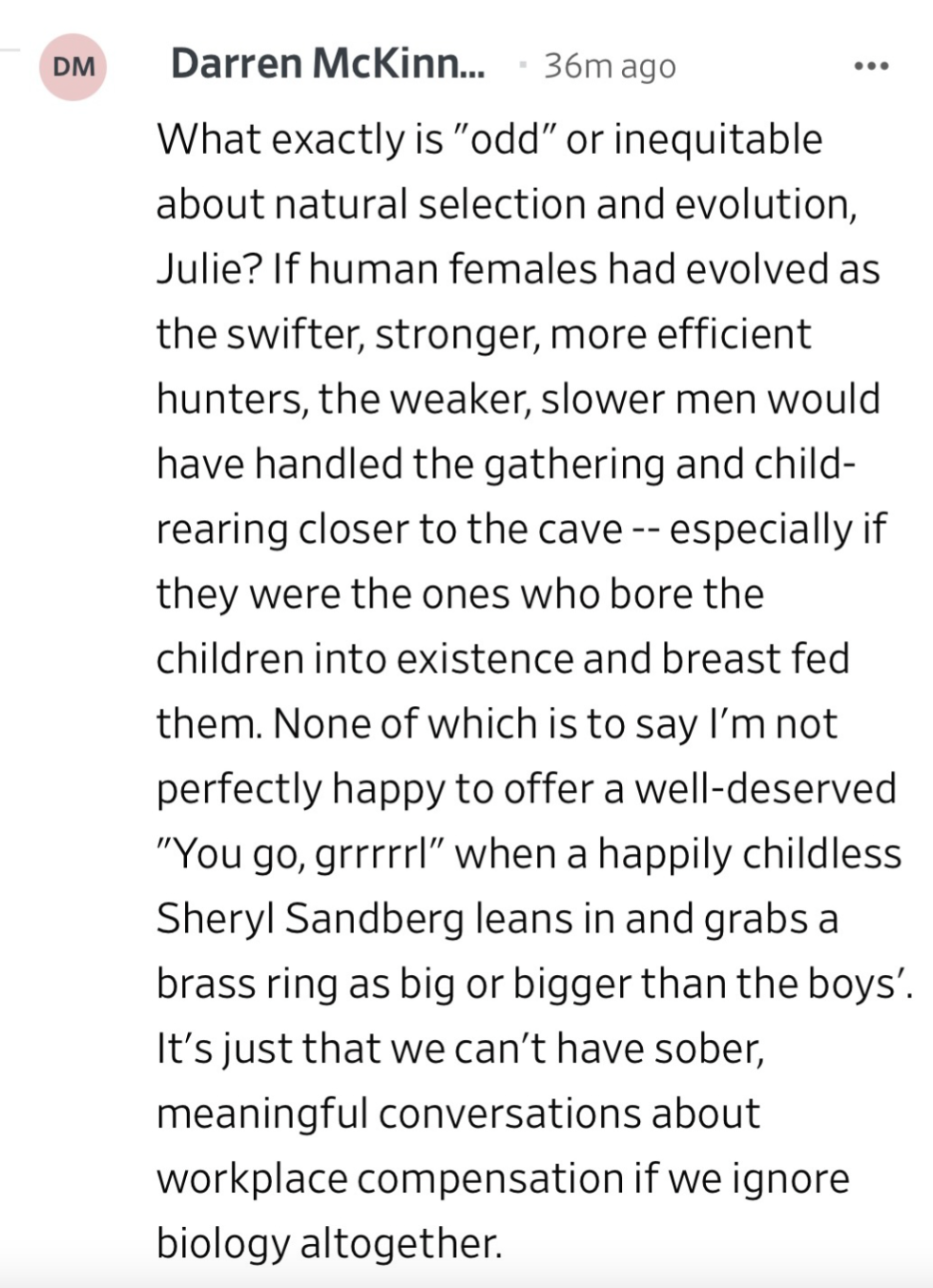

This is where things got juicy, because then commenter Darren piped up. I don’t think you’ll believe this actually happened if I just copy/paste it, so instead, I’ll share a screenshot that I took for posterity (you know, so I can show my daughter someday when she’s running for president):

And a thousand dog whistles sounded simultaneously.

My favorite line? “If human females had evolved as the swifter, stronger, more efficient hunters, the weaker, slower men would have handled the gathering and child-rearing closer to the cave.”

Because of course, only the strongest, fastest hunters are capable of the keyboard-punching knowledge work that requires one to be sedentary for nine hours a day. You’re so right, Darren, there’s no chance my supposed evolutionary “gatherer” skill set would serve me in the rough terrain of a cubicle farm—thanks for looking out for my vulnerable female frame.

Not to mention the fact that modern science is finding that these (largely Victorian male) ideas about “hunting and gathering” were—drumroll please—mostly wrong. Viking women were warriors. Prehistoric women did the majority of everything.

Biological destiny, or sociocultural preference?

This experience confirmed two things for me: Darren slept through his sociology and history classes, and there are a few too many biological determinists with Wall Street Journal subscriptions.

To back up a half-step, the original comment that fueled this incredible back-and-forth was actually correct—men, by and large, don’t “do the kid stuff.” Women do. As a result, women do, on average, work fewer paid hours than men.

The interesting thing, of course, about raising the “It’s because women are moms!” theory on this particular study is that most women two years out of Georgetown Law working for their first big firms are not yet mothers. Maybe even the potential for becoming a mother who may eventually sacrifice shareholder value to breastfeed is enough to suppress wages?

The other strain of pseudoscience that jumped out at me was this reliance in the rhetoric on “biology” and “maternal instincts.” If we’re to believe Darren, we can’t “ignore biology.”

>

“What will improve the circumstances at hand: Mandatory paid parental leave for all parents and some form of subsidized childcare.”

Darren would probably be surprised to know that the “natural” 1950s version of motherhood he’s referencing was not a biological evolution, but a unique blip in the human history of parenting: In an essay called “Maternal Instincts” by Laura Kipnis, she writes, “I don’t believe in maternal instinct because as anyone who’s perused the literature on the subject knows, it’s an invented concept that arises at a particular point in history (I’m speaking of Western history here)—circa the Industrial Revolution, just as the new industrial-era sexual division of labor was being negotiated, the one where men go to work and women stay home raising kids. (Before that, pretty much everyone worked at home.) What we’re calling biological instinct is a historical artifact—a culturally specific development, not a fact of nature.”

Reshma Saujani, founder of the Marshall Plan for Moms, is clear about what’ll improve the circumstances at hand: Mandatory paid parental leave for all parents and some form of subsidized childcare.

This is because women are often the de facto project managers of the home (burdened with the mental and physical load). If we’re able to legislate ubiquitous paid childcare and family leave, this will take much of the pressure off women to successfully perform two full-time jobs at once (one paid, one not-so paid).

While it would be easy to point the finger at policymakers for this one, unfortunately, the problem appears to be a little more complex.

Do all countries with paid family leave and subsidized childcare have more equitable workplaces? Unfortunately, no

Research from Harvard economics professor Claudia Goldin suggests that the cultural expectations placed on women may be just as powerful as policy: In countries where people express strong convictions that women should resign themselves to the domestic sphere, the observable pay gap for working moms is larger, regardless of policy.

For example, the pay gap between working women and everyone else in Germany is 3x larger than that in Denmark, despite the fact the countries have remarkably similar paid leave and childcare policies, per Bloomberg’s reporting. (Germany and Austria still maintain old-school ideas of a woman’s role in society and the home, while Denmark is a little more egalitarian. Scandinavia for the win part ∞.)

>

“Sometimes the laws are what drive the shifts.”

Despite the 1950s rose-colored glasses some people in Germany and Austria may be donning, it’s important that our laws work in lockstep with cultural shifts. After all, sometimes the laws are what drive the shifts.

But overall, the research suggests that the “motherhood penalty,” or the phenomenon wherein a woman’s long-term earnings drop by up to 10% for each child she bears (per Penn), has less to do with public policy and more to do with our deeply ingrained cultural expectations for women and social norms.

Curiously, men’s earnings do not drop after they become parents—they typically rise, per Duke. Boys will be boys, huh?!

What’s a mother to do? Lean in, Girlboss!

It’s probably understandable, then, why women have chosen to take matters into their own hands.

This approach (as we know it today) was first lionized in the 21st century in Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. (It’s worth mentioning that this idea is not new: Helen Gurley Brown wrote Having it All: Love, Success, Sex, Money Even if You’re Starting with Nothing in 1982. Notably, she omitted “sleep” in the title.)

Sophia Amoruso, founder of Nasty Gal and author of the book #Girlboss, was an icon for pink capitalists everywhere when she ignited this movement in 2014. And yes, I, too, read #Girlboss with breathless wonder.

It’s hard to deny that what Amoruso built was impressive: a company with a $200 million valuation with absolutely no outside funding. Only a small handful of people on earth can claim they did such a thing. And in perhaps the most ironic fall from grace possible given the title of this piece, Amoruso came under fire in 2015 for allegedly firing three female employees who were…pregnant and about to go on maternity leave. Le sigh.

The public outcry and backlash against Amoruso was swift and full-throated.

>

“Unilaterally criticizing individual women who have accomplished great things leads to its own sexist slippery slope, and blasting women who gain a foothold in male-dominated spaces is a frequently wielded weapon in patriarchy’s toolbox.”

While Girlboss is now an eponymous media company devoted to “helping women define success on their own terms,” the “Girlboss” ethos has come under fire in recent years after a few prominent successful women Girlbossed a little too close to the sun. It’s probably worth noting, too, that male founders with problematic track records don’t tend to receive this kind of ongoing scrutiny and attention after public fuck ups—no, they receive $350 million in fresh funding.

This is where things get messy. Unilaterally criticizing individual women who have accomplished great things leads to its own sexist slippery slope, and blasting women who gain a foothold in male-dominated spaces is a frequently wielded weapon in patriarchy’s toolbox.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay writes for The Cut, “#Girlboss is…the living embodiment of Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s order to lean in. The project was, on its face, necessary: The game is rigged against women who are, by all measures, as capable as men. But in mere months, the #Girlboss went from being an empowering idea to shorthand for a type of fake-woke feminism.”

Jia Tolentino also notes in her book Trick Mirror that the Girlboss ethos is attractive because it moralizes the imperative of “getting yours”; that individual wealth acquisition or ladder ascension is inherently progressive.

Sure, it’s pink-washed individualism dressed up as activism—but who could blame us? The whole reason Sandberg told us to “lean in” in the first place is because men have no qualms about pursuing wealth, success, and prestige. Encouraging women to shamelessly barnstorm the C-suite felt like really solid advice for creating a more egalitarian Corporate America. (Though there’s something about aspiring to Corporate America at all that feels vaguely dystopian, but I digress.)

Tolentino, of course, points out this brand of empowerment earns the bottom line-focused corporate sector’s stamp of approval—the “FEMINIST AS FUCK” T-shirts practically sold themselves.

But here’s the issue: Any solution that focuses too much on individual talent and achievement risks leaving others behind

It’s now clear to me that only making myself magnificently rich and successful does little to advance the position of all women. Individual success or exceptionalism on its own is not enough, particularly when women make up two-thirds of low-wage workers who are largely excluded from this type of corporate ladder-climbing advice altogether.

And lest you believe this social pressure is confined to the lower and middle classes, rest assured that even the most privileged and educated among us are not exempt. In anthropologist Dr. Wednesday Martin’s book Primates of Park Avenue, she documents her life marrying a hedge fund manager and moving to the Upper East Side of Manhattan to live amongst some of the most fascinating creatures of all: UES moms.

Her findings? Even having a lot of money isn’t enough to change cultural expectations about what counts as “work.” Martin concludes that wealthy, non-working moms can sense the disequilibrium and may not feel they’re equals with their male, breadwinning partners due to the disparity in their economic contributions to the family: “Access to your husband’s money might feel good. But the comparative study of human society and our primate relatives shows that such access can’t buy you the power you get by being the one who earns it.”

>

“Women’s unpaid labor contributes and enables between 10% and 40% of a country’s overall GDP, and the unpaid labor of American women is estimated to be worth $1.5 trillion per year. ”

You don’t simply lose your drive and relentless pursuit of success when you become a stay-at-home mom in the .1%: You just channel that ambition into “mommy pursuits,” like throwing the most face-melting class parties and charity events.

Whether you’re leaving your job because your husband is a hedge fund manager or you can’t afford to work and pay for childcare, the resultant feelings of inadequacy (and being generally undervalued) seem to be a constant across all socioeconomic strata (though, to be sure, those at the top are weathering those feelings from a much more comfortable vantage point).

Because surprise, surprise: Household labor is not recorded in GDP. This was a conscious choice, as the measure of “GDP” was invented to help make taxation decisions.

Still, the fact that I can earn GDP-relevant income raising someone else’s child (but not my own!) is a little…strange, if you think about it for too long. It’s especially strange when one considers women’s unpaid labor contributes and enables between 10% and 40% of a country’s overall GDP, and the unpaid labor of American women is estimated to be worth $1.5 trillion per year.

What’s important to remember, of course, is what Kipnis tells us in her essay: The motherhood-versus-career choice is not a biologically mandated choice. It’s a socially organized one, masquerading as a natural one.

The next time someone asks you about your plan for balancing work and family, be sure to stare at them quizzically and inquire if they’re asking their male friends the same question.

October 10, 2022

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time