In Investing, Fear Functions on a Lag: What History Tells Us About Stock Market Returns in Recessions

October 17, 2022

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

Inflation is at its highest level in nearly 40 years. Grocery budgets are straining at the seams. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the West answered with “I think the fuck not” plus oil sanctions that led to gas price spikes. The Fed is gluing down the button that raises rates and playing an unprofitable game of chicken with investors and borrowers alike.

Basically, we’re living through the 1970s all over again—and it feels like there are a lot of reasons to be pessimistic. Media in general—and financial media specifically—loves when things are going wrong, because negativity and pessimism drive far more clicks than a bland, reasonable message like, “Well, it’ll probably be fine.”

>

“Our perception of danger in the markets is highly uncorrelated with how dangerous the market actually is at any given time.”

Our brains are hardwired to perceive negativity as more truthful, more intelligent, and as a result, fear-mongering tends to run rampant when things seem like they are Going Very Badly™.

The alarmists are harmonizing the refrains of their favorite Sunday hymnal, This Time It’s Different, explaining (some with earnestly positive intentions, to be fair) that investing in the stock market right now would be a no good, very bad idea. This is usually followed by something about “fiat, bitcoin fixes this, whole life insurance or bust” on a droning loop. They shoot down messages of optimism as uninformed or unsophisticated.

Oh, how quickly we devolved from “Software is eating the world!” to “The only safe assets are physical bars of gold and Costco cans of Bush’s Baked Beans.”

When the vibes are off, it can feel safer to heed our gut instincts that something dire is afoot, pause our contributions to our brokerage accounts, and wait it out on the sidelines.

There’s only one problem: Our perception of danger in the markets is highly uncorrelated with how dangerous the market actually is at any given time.

But…is it a “no good, very bad” outlook?

A few weeks ago, I saw a comment entitled “Hard Lessons Will Be Learned” from an Anonymous Internet Opiner. They declared with certainty: “The next 40 years will not look like the last 40 years because of where we are in the big debt cycle.”

Ray Dalio has entered the chat.

“This lacks an understanding of macroeconomic trends.”

As soon as the tide turned from headlines of jpgs of rocks selling for $3 million to monkey-themed fan clubs to “the world is definitely ending” in nine months flat, it seemed internet comment sections were suddenly glutted with classically trained macro economists.

r/WallStreetBets called; it wants its analysts back.

>

“Fear is an emotion that functions on a lag. By the time we retail investors perceive the risk, it’s usually too late to do anything about it.”

But uh, do you know when we weren’t constantly wading through accusations of economic incompetence? When frequent conversations across the web didn’t co-opt Dalio’s talking points? When people weren’t beating the end-times drums?

In 2020 and 2021, when—as my friend Jack pointed out in this brilliant piece—risk was technically much higher than it is today.

That’s the problem with our perception of danger. We think it’s a lead indicator—a warning sign that something bad is going to happen, and we should act (or stop acting).

Unfortunately, fear is an emotion that functions on a lag. By the time we retail investors perceive the risk, it’s usually too late to do anything about it.

Back then, it was, “Have fun staying poor.” Today, it’s, “Macro trends tell us we’re headed for a flat decade.”

The critical, pessimistic sentiment online tends to be late to the party. It probably would’ve been a lot more helpful to spread a word of caution in 2021, when the S&P 500’s PE ratio was pushing 40, just about as high as it gets, rather than now, when we’re already down 25% YTD and the S&P 500 is roughly half as expensive as it was last year, with a PE ratio of around 18.

Right now, stocks are within one standard deviation of the historical average and are considered fairly valued by most measures. If anything, now would be the time to fire up the chorus of have fun staying poor, since the last two decades have proven that investing in something is just about the only chance regular people have of escaping chronic wage stagnation and declining purchasing power.

Of course, that’s not to say the market won’t go lower. That’s not to say there isn’t some macroeconomic trouble on the horizon. That’s not even to say this time it won’t be different, or that we aren’t headed for a flat decade—just that, all things considered, most of these doomsday Paul Reveres are about a year late. And ultimately? Nobody actually knows.

Even if bad things are ahead (like catastrophic events of the past that preceded recessions from which the stock market eventually recovered—a Great Depression, a housing market implosion, a massive terrorist attack, a Gulf War, an oil embargo, or…well, I think you get the picture), we have a relatively solid idea of what typically happens when shit goes awry at scale, thanks to the last 100 years.

Stock market returns through recessions are less predictable than you’d probably expect

As much as I wish past performance was indicative of future returns…it’s not. That said, history is just about the only (hazy) crystal ball we’ve got for understanding a probable range of outcomes.

Moreover, the stock market is forward-looking—it’s not reacting to what’s already happened in the same way that our flighty amygdalas are. It’s anticipating what’ll happen six or 12 months down the road, which means it usually goes down before a recession actually starts (and usually improves before a recession ends).

And one of the key recession indicators—high unemployment—isn’t really happening yet. (The technical language for this phenomenon is the “recession isn’t recessioning,” and J-Pow & the Fed Boiz are probably going to keep hiking rates until it does.)

This is why a strong jobs report actually made the stock market react negatively, because a strong-ish economy probably means more rate hikes. The market—comprising a bunch of smart, greedy people—is pricing in something it’s expecting to happen in the next few months. (You’ll never convince me the stock market isn’t just a mood ring in the short term.)

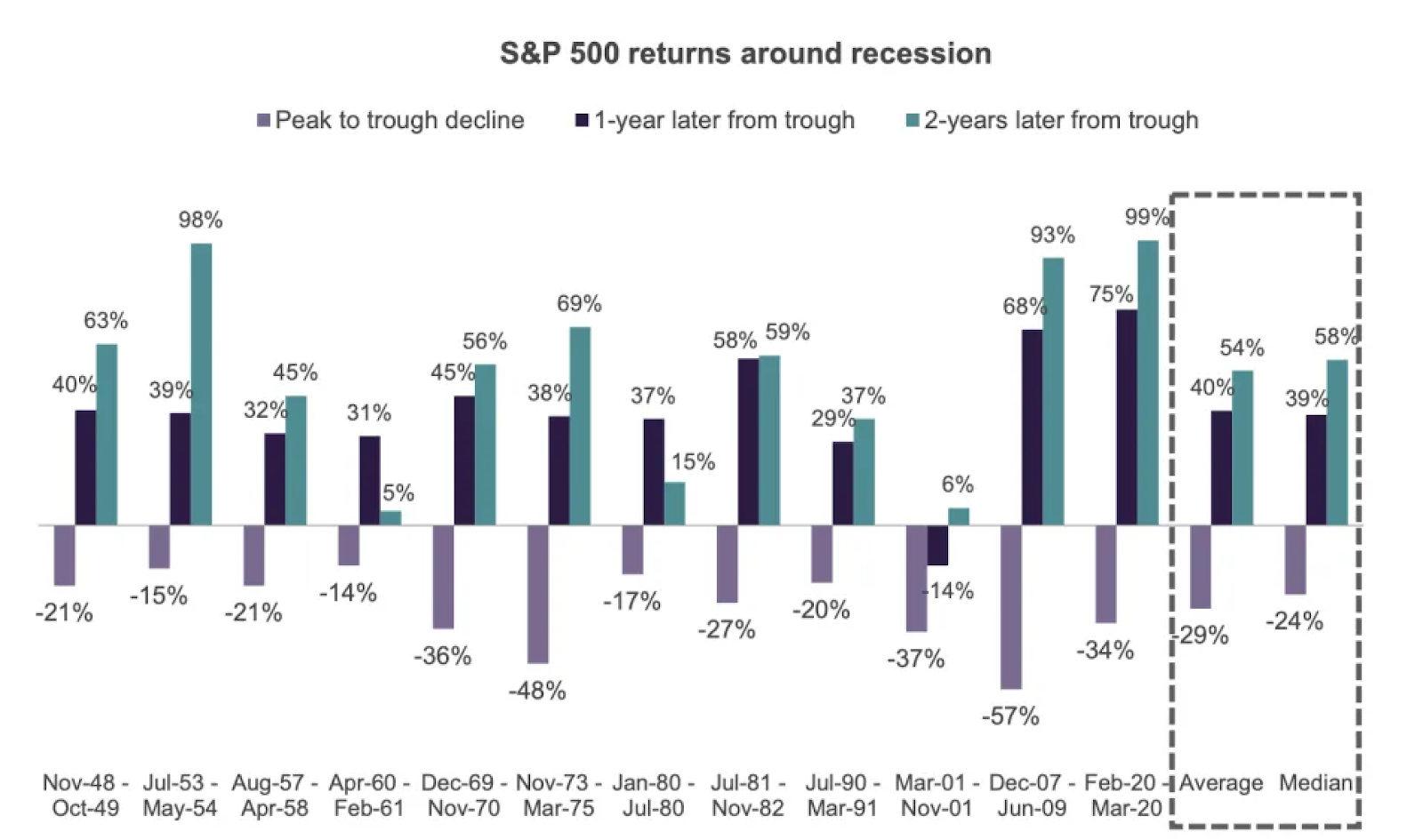

The chart below shows us that the range of drawdowns during recessionary periods in the last 72 years was between -14% and -57% (woof). But it also shows us the returns on cash invested at or around the low point two years after each “bottom,” ranging from 5% to 99%. (This means a dollar invested during the market’s lowest point in a recessionary plunge returned anywhere from 5% to 99% in the two years that followed.)

Chart courtesy of Yahoo! Finance.

These ranges are about as wide as they come. The median drawdown, however, is -24%, which is approximately where we are right now.

The point isn’t to estimate how bad it’s going to get—there are far too many variables for that—but to exemplify the fact that it’s almost impossible to know. There’s no discernible pattern to extrapolate forward.

Is this the bottom? Who knows? The macro buffs would tell you we have much farther to fall (because of money printing, because of war, because of inflation, because of Jerome…or because negative press is what gets clicks), but nobody actually knows.

The one thing that is clear from this data is that the money you invested through every recessionary bottom in history always looks all right two years later, and the only way to guarantee you invest at the bottom is to invest through all of it.

Might as well bet on 100 years of historical precedent if you’re going to bet on anything. As Jack Raines wrote: “Risk is highest when we forget it exists, and lowest when it’s all we can think about.”

Maybe the Bear Bros will rejoice from their alternative asset classes that they were right and the dumb, optimistic masses were wrong—but if you’re coming to that conclusion in October 2022, you’re probably too late to do anything about it anyway.

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time