Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

A cherished milestone of modern American adulthood is rewatching the 1990 classic Home Alone through Zillow-pilled eyes for the first time, witnessing the wings on either side of the McCallister house, and realizing, woah, those people were rich. So much so that a fun New York Times piece set out to determine just how rich, 33 years after the film was released. In the article, writer Amanda Holpuch speaks with a sociology professor about the class dimensions of the John Hughes film: “[Hughes’s] stories usually favor the perspective of the working class kid or the poor kid who is trying to gain access to a wealthier peer group…[b]ut in ‘Home Alone,’ it’s…Kevin as a rich kid defending his impressive fortress.” In 2025’s economic environment, the only thing more startling than the McCallisters’ five-bedroom fortress is their five children.

In the United States today, it costs around $300,000 to raise a child from birth to age 17. This doesn’t include higher education, which adds, on average, another $150,000. (When we covered the “real” costs of childcare on the show last week, the primary critical feedback was not that they were wrong, but that they were simply a huge bummer.) With a price that steep, it’s no wonder a movie about a family of seven—flying to Paris for Christmas, no less—feels particularly rarefied.

Of course, big families represented in popular culture are not new: The Brady Bunch, a show about a blended family of eight (nine, if you count Alice, the family’s live-in maid), first aired in 1969. Almost 40 years later, a different blended family changed television forever in a show called Keeping Up with the Kardashians, which followed Momager Kris Jenner, her grumbling spouse, and their six kids around ritzy Calabasas as they manufactured reality TV hijinks. Since then, the family has only mushroomed larger as the girls (sorry, Rob) gave birth to broods of their own. The eldest daughters, Kourtney, Kim, and Khloe, have 10 children between them, more than replacing the original cast. (It’s only a matter of time before the next generation of spinoffs start.)

If once otherwise conceived in popular imagination as a vector of fundamentalist religiosity (more reality TV: “19 Kids and Counting”) or a low-income stereotype associated with farming and self-sufficiency, the “large family” is in the midst of a conspicuous rebrand. In today’s media landscape, they’re much less “bunk beds and hand-me-downs,” more “professional birthday parties and Burberry Baby.” This aesthetic shift betrays an economic one: Having more than one child in America is so expensive, it’s practically a luxury good. Whether supported by a single breadwinner or two professionals with the means to pay for childcare, having a large family is becoming akin to a status symbol. This is a natural consequence of the costs associated with children continuing to rise at double the inflation rate for 30 years: Left unabated, we’ll soon come to think of “having kids” as something only rich people do.

Left: What “having a big family” conjured in the popular imagination just a few years ago (religious, hand-me-down clothes, etc.). Right: The glossy, well-lit high-income vision of “big family” in American popular culture today.

The anxieties that ripple through reporting about the birth rate collapse or worm their way into awkward, sweeping political statements practically begging for “more babies in America” feel incongruous with the lives I observe on my various screens. Most of the popular figures that flit across my feeds, whether famous actresses or billionaires or the more amorphous “lifestyle influencers,” have oodles of kids. Sometimes the children are explicitly part of the brand’s central value proposition (à la the cursed family YouTube channel), but usually, they exist on the periphery, like accessories.

First, there are the billionaires: Elon Musk has 13 children with four different women. Chamath Palihapitiya, noted billionaire-turned-SPAC rugpull connoisseur (not necessarily in that order) of “All-In Podcast” fame, has five with two. Sara Blakeley, the youngest self-made female billionaire at 41 (if you, like me, thought it was Oprah, she was 49), does not have the luxury of multiple wives, and thus pulls up the rear of this group with four. In 2022, Forbes reported that there were “22 U.S. billionaires with seven or more kids,” including, I learned, Steven Spielberg. (This was three years and four children ago for Musk.) I don’t know what The Economist is so worried about—it certainly seems like some people are having children, and lots of them!

Then, there are the influencers. Often hailing from the B-team Real Housewives franchise cities (think Dallas, Salt Lake City), their brands are ostensibly about “fashion” or “travel” or the more nebulous “lifestyle”—but more often than not, the unifying theme is just “wealth.” These grids are populated with walk-in closets full of luxury logos, lush waist-length hair extensions, matte black SUVs, and yes, usually no fewer than three young children, who are as fundamental to the aura of abundance as the Hermès and Chanel bags. Influencer Krystiana Tiana has more than 15 million followers across platforms and five children. Kristi, a New York City fashion and lifestyle influencer with 400,000 followers, has five as well. Fashion influencer Madi Nelson has a million followers, but only four children. It goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: Hannah Neeleman (better known as “Ballerina Farm”) reigns supreme in this category, with eight kids and 22 million followers.

The lucrative influencer career—especially the sort that centers a performance of upper-class motherhood with five or more children—is a notable subversion of the typical earnings pattern observed when a woman has kids (that is, incremental, permanent decreases in income associated with the birth of each child). It’s the ultimate “classy if you’re rich; trashy if you’re poor” case study, a polarity that will only grow stronger as the parenting premium rises.

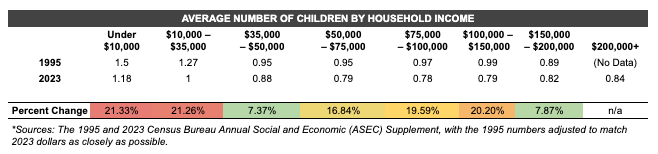

While the average number of kids by household income group has fallen across the board over the last 30 years, it fell most dramatically for those at the bottom and in the middle. Comparing inflation-adjusted income and family data from 1995 to the last available figures for 2023, households earning less than $35,000 saw roughly 20% declines, as did those earning between $75,000 and $100,000. Compare this to the $150,000–$200,000 range, which declined by only about 8%. And while it’s true that people at the very bottom of the income distribution still tend to have more kids on average than those at the top, households earning more than $200,000 (the upper limit in the data set) represented around 19% of the population in 2023—but accounted for nearly one in four families with five members (most often, this means three kids).

Typically, “choice” is the lens through which we view and discuss decisions about children (whether to have them, how many to have, etc.). But the reproductive justice framework, created by the Black Women’s Caucus of Illinois in 1994, provides an instructive critique: “Choice” is relatively meaningless if you’re structurally limited by a narrow set of options—like, say, state-sponsored forced sterilization, or childcare for one kid that costs more than your mortgage. While most often associated with abortion access, reproductive justice is equally concerned with protecting the human right to have children.

Some societies organize around this notion—not only that humans have the right to have children, but that caring for them should be a matter of public responsibility, rather than a privilege mapped to the bounds of one’s personal income. In 1981, around the same time Ronald Reagan grabbed the US by its bootstraps and yanked hard, Norway appointed its first woman prime minister, Gro Harlem Brundtland. Norway, a country roughly equal in population today to the state of South Carolina, already had a maternity leave of around 4.5 months by the time Brundtland took over. Pappapermisjon, or paternity leave, came later, in 1993.

Today, the parental leave policy in Norway offers parents 100% of their salary (up to six times the “basic” income in Norway, about $67,628) for 49 weeks or 80% of their salary for 61 weeks. (This is in addition to the government-mandated five weeks of paid vacation to which full-time workers in Norway are entitled.) Biological mothers also receive paid pregnancy leave, or between three and 12 weeks of paid time off leading up to their due date. The government reimburses employers for the wages.

“The state chose to take responsibility for planning, providing, and paying for childcare through a series of laws,” writes Natasha Hakimi Zapata in her book Another World is Possible, beginning not in the pandemic-era 2020s, but in the 1970s, just a few years after the 1969 discovery of oil in the North Sea made the country rich. By 2005, all resident children of Norway were granted the right to a place in a barnehage, or childcare center, after age 1, when parental leave ends. It costs, at the high end, around $287 per month. For an extra $20 per month, daily meals are included. Families earning less than around $33,000 can qualify for 20 hours of free care per week. Around 93% of Norwegian kids attend these centers where the care workers are early childhood educators, many of whom hold advanced degrees. All this thanks to radical socialist principles, like the right of a parent to bond with their child without losing their job in the Amazon warehouse!

Curiously, these policies aren’t reflected in Norway’s birth rate, which is lower than that of the US. But this is only evidence of some failure if you believe (like the billionaires, apparently) that the blunt object of family size is the best measure of prosperity. The real difference isn’t captured by “Live Human Births Per 1,000,” but by a flow of collective abundance wielded less like a privately contracted firehose and more like rainfall.

Norway is an example of what it might look like to design an economic and public support system around the belief that every person has a right to a family. In America, we orient around a different aphorism: “Don’t have kids you can’t afford.” But what will happen when (almost) nobody can afford them anymore? Will American children, like American wealth, pool with the one percent? A more distressing question: How long has it already been a luxury? (I’m reminded again of the Brady Bunch family and their live-in maid.) Another way is not only possible—it already exists somewhere else.

Data sidenote:

There’s just one subgroup for whom the decrease was similarly low: those earning between $35,000 and $50,000 in today’s dollars. Since the 1995 and 2023 data sets were presented differently, I did my best to (a) inflation-adjust and (b) normalize the value ranges so they could be compared more easily, but these ranges are approximate.

February 17, 2025

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time