Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

There are a few notable examples of overlap between traditional personal finance advice and economic justice movements. Take, for example, last Friday’s “Economic Blackout,” organized by a group called The People’s Union. The Blackout challenged Americans to avoid shopping at megacorporations like Target or Amazon for a single day (Friday, February 28), an idea which Newsweek dubbed “a potent message” about “consumer power” and “corporate accountability.” This sort of message—stop shopping—is right at home in personal finance canon, particularly among the FI/RE faction of the industry. This isn’t frugality pitched as boring, lame self-restriction—it’s frugality as revolution. The boycott was covered by national publications including NPR, Fast Company, USA Today, AP News, Forbes, and Time, all of which awkwardly danced around a central question: Does a 24-hour spending boycott…matter?

The founder of The People’s Union, John Schwarz, expressed his beliefs during an Instagram Live Thursday night that seemed to send mixed political signals: He mentioned an interest in “eliminating federal income taxes” (a Trumpian fixation), “capping profits for corporations” (appeals to both the populist right and the Bernie left), and “promoting equality for all” in response to Target rolling back DEI policies (scans as liberal). This lack of coherence isn’t necessarily a bad thing: Part of what a good class analysis should emphasize is that a working Republican and working Democrat have far more in common with one another than the billionaires who lead their respective parties.

Did the one-day boycott teach Target a lesson? The short answer is probably “no,” but the long answer is more complicated and worthwhile. An effort like this could’ve cultivated a sense of solidarity, or demonstrated the scope of opposition to the hegemony of corporate interests. (The group’s website outlined a flurry of more targeted boycotts to come, indicating this one-day abstention was merely a warning shot.) But within two days, the movement’s focus was fraying, as Schwarz’s checkered past and GoFundMe page came under scrutiny. Our willingness to curb consumption or engage in political action is fragile enough—scandals don’t help.

>

“What a good class analysis should emphasize is that a working Republican and working Democrat have far more in common with one another than the billionaires who lead their respective parties.”

A woman whose post about the boycotts went viral (“Beyoncé’s mother shared it!”) posted a Notes app follow-up to express her discomfort with the founder’s videos asking for donations: “…I saw the fundraising on the website and multiple videos pushing people to donate to some platform we don’t need. My stomach dropped. Boycotting and collective action are crucial, but this? This is a huge red flag. There is absolutely no reason to give this person money—it’s giving cult leader vibes.” The GoFundMe page in question, linked on the site’s Donations tab, has raised more than $117,000. The site states the funds are needed to expand the website, establish an official membership system, hire volunteers and employees, cover legal fees, and eventually, create a “citizen’s union,” all reasonable enough.

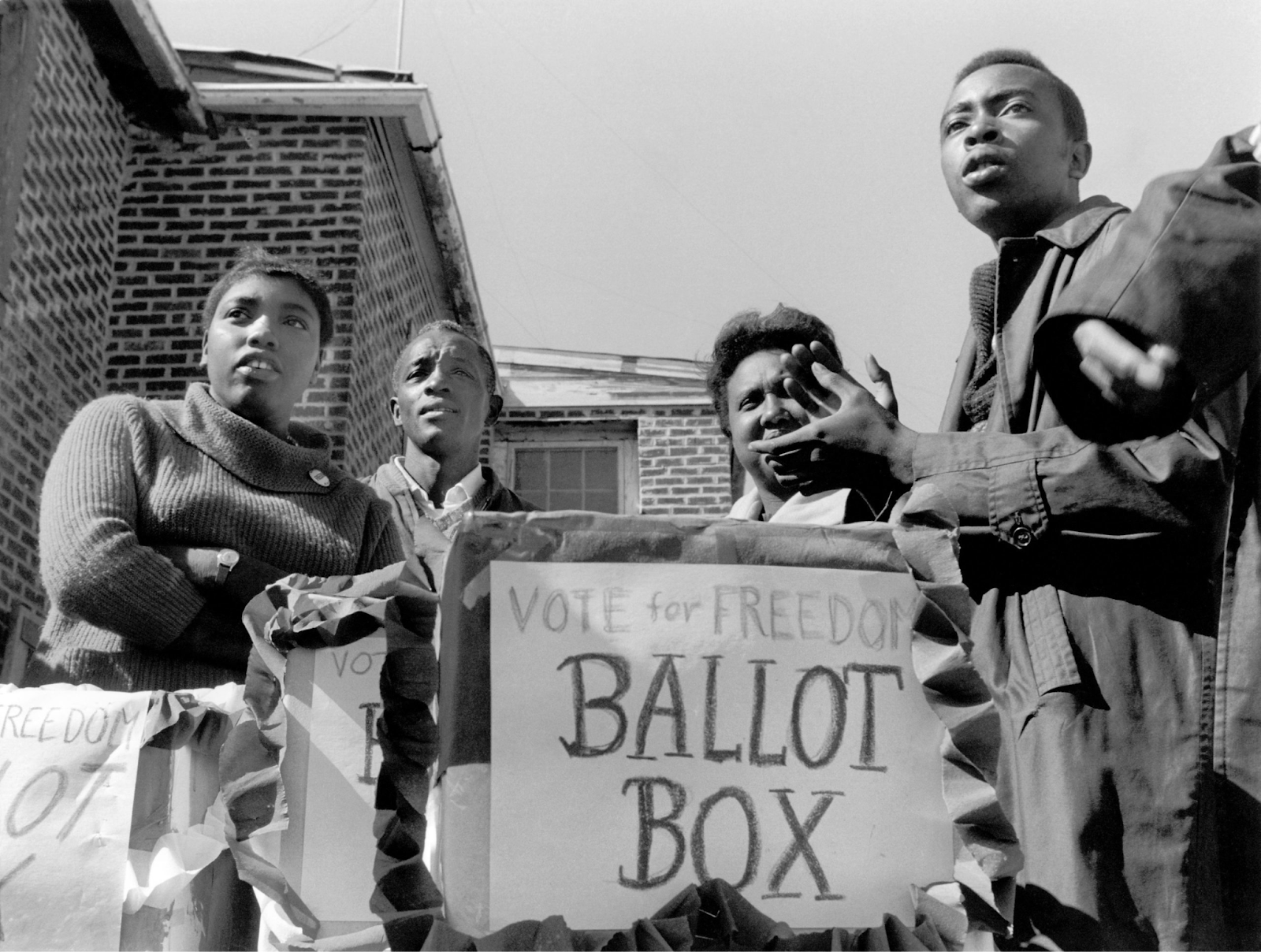

Being suspicious of calls for resources is as understandable as it is revealing: We’ve become so conditioned by an online environment of rampant scamming that a social movement requesting donations is “a huge red flag.” Schwarz may or may not be a grifter, but the existence of a GoFundMe is not proof of wrongdoing on its own. The fuel of most successful movements is, for better or worse, money: Sustaining a single Mississippi-based voter registration drive during the Civil Rights movement required the modern equivalent of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A History of Domestic Work and Worker Organizing.

Still, it all felt familiar: a hopeful social media blitz followed almost as quickly by an anticlimactic womp-womp in an age when movements are adjusted for the aspect ratio and ephemerality of a given platform’s infinite scroll. The last few decades have seen rising economic disparity, but they’ve also featured an explosion of material creature comforts, at once pacifying and overwhelming—our feeds make us more aware of problems to the exact degree they make us feel powerless to do anything about them.

Americans, who have been trained to think of themselves as consumers first and citizens second, may recognize withholding their purchasing power as a valid path to reform, but effective boycotts require specific demands: We’re going to do X (withhold our money) until you agree to do Y (pay your workers more). That’s not to say permanent divestment isn’t a valid path, just that it’s a different tactic from calling on a group to temporarily protest something. The success of movements from bygone eras required an almost unbelievable willingness to endure prolonged inconvenience and potential violence—take the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a year-long protest in which Black Americans refused to ride buses in Montgomery, Alabama, nearly bankrupting the bus lines. The movement grabbed enterprise by its throat, leaving it no choice but to comply, eventually culminating in a Supreme Court decision that declared such segregation unconstitutional.

In Marion Teniade’s piece about an even more diffuse effort organized on social media earlier this year, she enumerates where we tend to go wrong. “There’s no specificity to a call to #BoycottTarget. Because, how are we boycotting? What alternatives are we using? And for how long? Until we get what? With no specificity or feasibility, there’s no accountability or impact.” This is downstream of social media’s architecture: A hashtag amplifies ideas, but it also flattens them. The resultant inefficacy has the effect of leaving demoralized participants mumbling something about “no ethical consumption under capitalism” while traipsing back to Target for a Frappuccino and Good & Gather fruit snacks at the end of a long day.

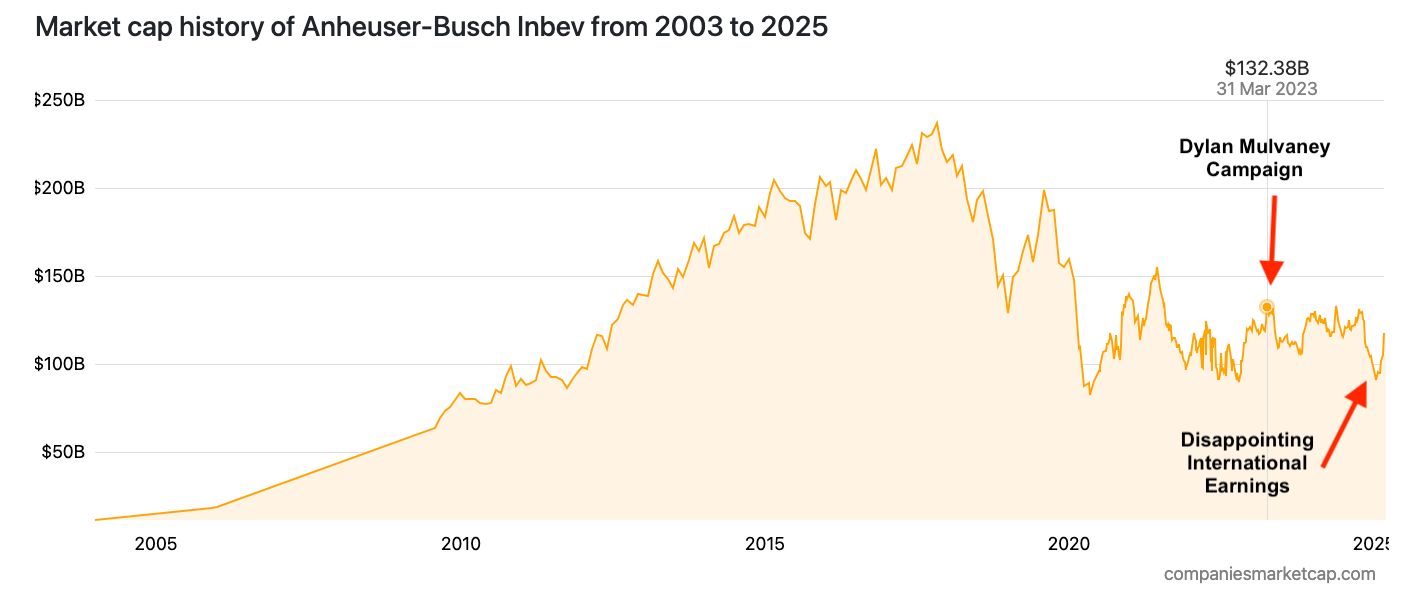

What’s interesting in this cultural moment is that neutered consumer action transcends party lines. After Bud Light partnered with a trans woman for a single social media campaign, everyone from Fox News hosts to chronically online right-wing anons melted down, engaging in increasingly absurd spectacles to demonstrate their disgust, like Kid Rock opening fire on a case of beer.

That’ll show they/them.

Anheuser-Busch suffered some short-term losses to sales and a deflated share price during the months it was in Fox News’s crosshairs, but most of the erosion happened years before it shipped Dylan Mulvaney a case of beer. Its real challenges of late have been declining sales in South Korea and Brazil because of price increases. Exhibitions of fury concealed no actual demands, so calls to “boycott Bud Light” eventually lost steam because of their aimlessness. Boycott them until what happens, Anheuser-Busch issues a statement clarifying its position on the gender binary?

American corporations are stuck in a tug-of-war between two polarized political parties, making symbolic concessions to appease whichever group seems culturally dominant at the moment. Of course, these companies are probably thrilled we’re too preoccupied chasing the laser pointer of branding and influencer marketing to pay attention to things like, I don’t know, profit margins and labor practices. Who could forget Tucker Carlson bemoaning the sexlessness of his beloved Green M&M? Progressivism is, apparently, about making cartoon chocolate less promiscuous. Meanwhile, nearly 80% of Americans are unable to afford the median home.

There was a time when the internet seemed like a more promising tool for organizing. A 2001 paper about the anti-sweatshop campaigns of the 1990s targeting Nike’s overseas production cited examples of online activism, the descriptions of which now seem quaint: “There are a number of host sites promoting activism on the web, some of them very general and others addressing a particular concern, industry, or company,” one section called “Web Resistance,” explains.

Business Insider.

In many ways, these early iterations were far more robust: The Nike protest organizers used the nascent internet to disseminate resources, like “a Campaign starter kit, which consists of a letter to Nike CEO, Phil Knight; a petition; a city anti-sweatshop resolution; a sample student government resolution; a sample letter to the editor; and recent accomplishments of activist strategies…” plus a litany of tactics for planning protests and sample speeches for delivering at “local churches, schools, and community centers.” The paper concluded: “The flexibility of the Internet as a mobilizing resource…fosters critical thinking, compassion, equality, and activism. It also gives citizens a way to define social problems in ways not depicted by the mass media or corporate-dominated society.” (Critical thinking? Compassion? Who’s going to tell her?)

Written several years before the advent of social networks, the author clearly had high hopes for how the internet would shape a better world. These platforms have become the dominant mode of connection online, despite the fact that their infrastructure is set up not to connect people, but to sell them things. Similarly, Bud Light partnered with Dylan Mulvaney not because Anheuser-Busch wanted to take a stand for the rights of trans people, but to sell beer to Dylan’s nearly 10 million TikTok followers. They did it for the same, boring reason any brand partners with any person: to gain market share.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported—unironically—that “BlackRock’s woke era is over.” The piece was in reference to a spate of updates from the manager of $11 trillion in assets, including a change to hiring practices that “would no longer require managers to interview a diverse slate of candidates for open positions” and its “withdrawal from the climate coalition.” Apparently, oil-and-gas lobbyists and the Federalist Society began targeting ESG in 2022, accusing it of “woke capitalism.”

In an op-ed, a disgruntled former Anheuser-Busch executive reflected on the Mulvaney controversy, identifying this same force as the culprit: “I define woke as a view that businesses and brands should support liberal causes, even when those causes have nothing to do with what the company does. ‘Woke CEOs’ use their position to advance a progressive political ideology unrelated to their corporate role.” But this explanation is a head-scratcher for the same reason “woke capitalism” is an oxymoron: You cannot meaningfully leverage your role as CEO of a Fortune 500 company to “advance a progressive political ideology,” because actual progress is at odds with how most Fortune 500 companies operate. In the absence of substantive reform, we’re left with empty platitudes meant to placate a population of customers now equipped to demand the language of social justice but not the underlying principles.

>

“Any boycott that is not chiefly concerned with economic justice is handing corporations the easy way out.”

It’s true that brands were quick to slap rainbows on products or host diversity trainings, to pump press releases and ad campaigns full of commitments to gender equity or racial justice. They were slower to implement any sort of economic equity or justice within their balance sheets. The examples are dizzying: It’s the celebration that Raytheon has a female CEO, as Raytheon manufactures bombs. It’s Target producing loud-and-proud Pride collections under one administration, then renouncing company goals of inclusion under another. It’s Starbucks getting lit up for opening its (probably gender-neutral) restrooms to the public, while at the same time quietly busting unions and retaliating against striking workers. It’s McDonald’s issuing a “Global Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Report” stating its commitment to “breaking down barriers so more people can access the opportunities for prosperity,” while at the very same time being one of the largest employers of full-time workers on SNAP and Medicaid.

A brand can pay lip service to “progressive ideology” however it likes, but there’s no legitimate version of justice that involves breaking labor law or exploiting your workers. In other words: Corporations are ideologically empty vessels of commerce which support or disown “woke” ideas only to the extent those ideas can be used to sell more stuff. Any boycott that is not chiefly concerned with economic justice is handing corporations the easy way out.

Despite all this, it makes me hopeful we’re having this discussion at all—John Schwarz is a random person who bought a web domain and declared an “Economic Blackout Day.” Within weeks, it was covered by outlets all over the country. Could starting a movement that gets signal-boosted by mainstream media really be that easy? (Or did mainstream media legitimize it precisely because it lacked teeth?) Regardless, what might it augur for the future that Americans are this starved for an avenue to voice their frustrations, this readily engaged?

At present, our biggest economic challenge is an embedded sense of powerlessness, which means most financial advice is limited to the identification and implementation of capitalist principles: If you ever want to retire from wage labor, you must become an owner of “income-producing assets,” as they say. Regular people who don’t inherit large sums of money really only have one way of achieving this: working for a wage then saving part of it to buy assets.

But our real lever of influence might be located on the opposite side of the transaction—not with people acting in their capacity as shoppers, but as shareholders and workers. Consider the GameStop short squeeze of 2021, in which a group of regular people rallied around a man who noticed Melvin Capital’s short position. He encouraged everyone to buy the stock, relentlessly bidding up the price and nearly destroying the $13 billion hedge fund. Melvin was bailed out and temporarily saved by two other hedge funds, but it wasn’t enough to reverse their fate. In 2022, Melvin Capital wound down operations. It’s genuinely remarkable that a group of retail traders congregating in an anonymous online forum set off a chain of events that ultimately brought down a hedge fund, even if it didn’t cause longer-term financial reform.

Power balances are a delicate dance: If a government or corporation (or, in the case of America’s unique fusion, state-sponsored corporate power) believes it maintains total control, anything capable of disrupting this illusion matters. A Journal of Democracy article explains the balance of power in France. “French workers, students, and others are regularly on strike or protesting in the streets because…strikes and street protests are probably the most meaningful check on presidential power left to the public,” it says, “and sometimes the only way the people can have a voice in political and economic decision making.” In other words, regardless of the outcome of any one specific protest, the protest itself is a mechanism by which power is kept in check.

These moments pierce the veil of corporate impenetrability, reminding people of an easily forgotten concept that became a rallying cry for the meme traders: “apes together strong.” There is value in flexing that reality, like a muscle at risk of atrophy, even if a specific initiative falls short. There may be valid critiques of the recent Economic Blackout, but there’s only one we should take to heart: We just aren’t thinking big enough yet.

March 3, 2025

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time