What Actually Happens When You Retire Early?

January 11, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

My forever weekend plans post-working.

A lot of the time when I cover fairly complex topics on this blog, I’m doing it for myself just as much as I’m doing it for the kind people who are gracious enough to spend their time on this site.

Early retirement – and the logistics therein – is one of the topics about which I’m currently a little bit fanatical.

The pre-early retirement phases are pretty obvious to me: Max out tax-advantaged accounts, dump as much as possible into taxable accounts afterward, and spend as little as comfortably possible so you can retire before you’re 40.

The post-early retirement process eluded me a little bit. A few of the questions that I had:

-

If I’m retiring at 40, how am I going to touch the money in a 401(k) or IRA (accounts that are designed to be used when you’re pushing 60, not rounding home at 39)?

-

Even if I save a total of $1M across a bunch of different accounts, how do I know the order to use each one? Will this math still work if I’m spending a little from one account and a little from another, and the money isn’t all in the same account?

-

How do I fold in the fact that I’ll probably still work and make some money, in some degree?

-

What about healthcare? That’s expensive, and it’s not currently an expense of mine. (Spoiler alert: This is still a question.)

Nothing felt too pressing, as I’m still very much in the “shovel as much as possible into investment accounts” phase, but there was a sense of, “What if I’m making some small mistake in my strategy right now and it derails my plans?” looming right under the surface.

Today, I want to flesh this out – for me, and for you – so we can see (together!) what this looks like in practice.

Pre-research

Some of my questions (as noted above) were answered through reading Financial Freedom by Grant Sabatier and listening to a few episodes of ChooseFI (specifically episode 43, on drawdown strategy). All that to say – “FIentists” smarter than me informed this strategy, so rest assured I didn’t pull it out of my ass, and the fact that I’m still about 10 years away means this strategy will probably change as tax law, my lifestyle, and other factors change, too.

Cruising into early retirement

I’m not sure when, exactly, I’ll hit FI – my income situation is really bizarre right now, and I don’t think all my streams of income are ultimately sustainable beyond a few months (they very well may be, but I don’t want to count on it).

For the purposes of this exercise, I’m going to use a projection calculator that uses a high monthly contribution average for each of my major accounts to determine at what point I’ll have enough in my accounts to retire (to make it nice and round, let’s say $1M is my number – this would enable me to withdraw $40,000 per year for living expenses).

This is the projections tool that’s built into the Wealth Planner , so it will make these projections for you based on your numbers, too!

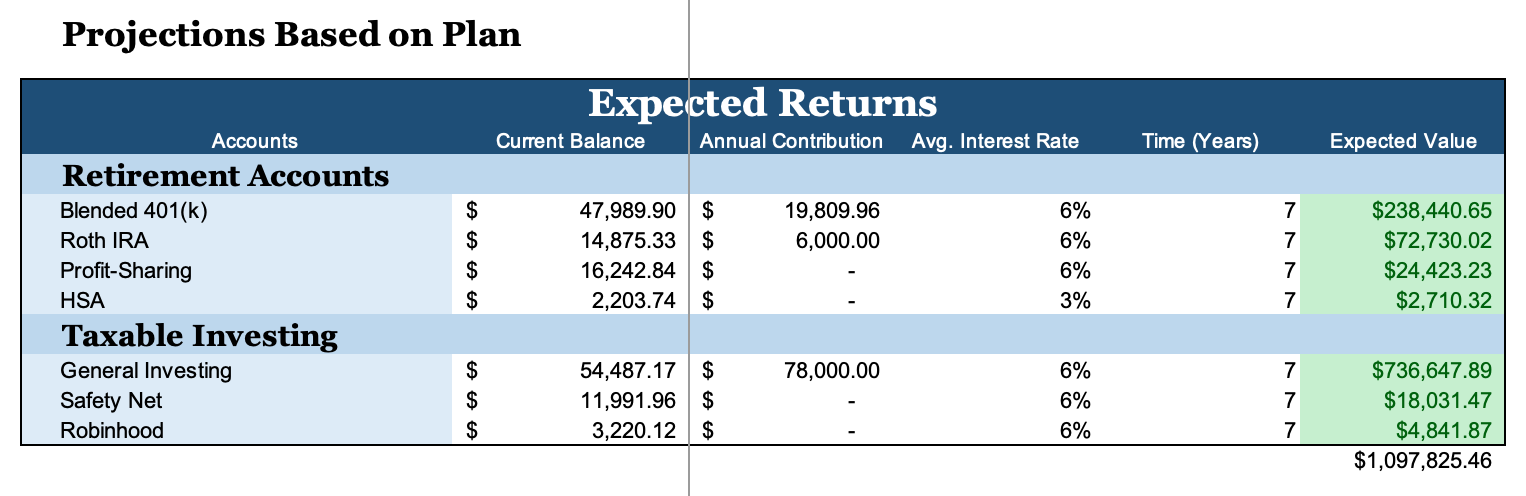

If I can max out my Traditional 401(k) (and get the full employer match), max out my Roth IRA, and contribute the leftover investable money each month into an individual brokerage account… I should be set within 7 years (assuming an average return of 6% in the markets) to retire with $1M at age 33.

Of course, this is assuming I don’t get fired from all my jobs, break my legs, or become increasingly more incompetent (no promises). Remember the part where I said this is projected out based on my current higher streams of income continuing? They are all – by their very nature – temporary, so I can almost guarantee you they won’t.

Don’t focus on the contribution timeline. This is really just an exercise in, “How much can I motivate myself to find OTHER streams of income when my current engagements end?”

The important part of this article is not how quickly we can reach early retirement, but what happens once we get there.

For the sake of this exercise, let’s plow forward knowing that my timeline is likely longer than 7 years and probably closer to 10 or 12.

Where would this put me, theoretically?

I’d have $238,000 in my 401(k), $72,000 in my Roth IRA, $736,000 in a taxable account, and $18,000 in my emergency fund. Because we’re being conservative in these estimations (which just feels safer to me), I’m not including the investment accounts I have to which I’m not actively contributing anything (about $15,000 in a profit-sharing account and $3,000 in a Robinhood account).

Because simplicity makes this entire process easier (rather than having 15 different investment accounts scattered throughout the financial world), I’m trying to focus my attention on the heavy hitter, major accounts. I’ll probably, at some point, do the legwork to combine certain accounts, but for now I don’t want to create any more taxable events than I need to.

A few things to note right away about the “best practices” of early retirement…

-

When I start to get close to retirement, I’ll probably increase my 6-month emergency fund to 12 months of emergency fund. This bucket of cash will be my safety net in the first 1-3 years of early retirement to make sure I don’t need to tap into the principal balances in any of my investment accounts. Because I’m retiring early, I’m relying on my investment accounts to keep growing indefinitely, which can create some precarious math in “down” markets – if you have a few bad years in the beginning and withdraw too much, it can derail this whole shindig. The takeaway? Very important to have enough cash on hand for the first 5 years. If you can get through the first 5 years with all your principal balances intact, you’re almost certain to have enough money forever and still some to pass down to your kids, charities, rescues for tabby cats with spunky personalities… not to name any names, though!

-

See my Emergency Fund up there? That pretty little $17,000? The tough part is, that’s actually invested, too – in early retirement, investment accounts like the Betterment Safety Net (85% bonds, 15% stocks) help your “cash” grow more quickly than if it were just sitting in a savings account (you may have even noticed that the account grew by about $3,000 over the 10-year period despite no additional contributions), though I did a sweeping 6% return across all accounts and that’s probably a bit high for Safety Net. The tough part? It’s invested, which means when you “cash it out” (in other words, sell your positions and take the cash-money), you’ll be taxed on it (I’ve got an exhaustive – and I’m talking Masters level, graduate studies course vibe – post coming on Safety Net in a couple weeks, so stay tuned).

Loophole alert! In 2020, the long-term capital gains tax for amounts under $40,000 is 0%. That’s right – as long as you’re selling and withdrawing money from an investment account in which you’ve held all the stocks (read: index funds) for longer than a year, you pay no taxes on the first $40,000 of capital gains if you have no other earned income.

In other words, when your earned income drops to $0 in early retirement, the first $40,000 you withdraw from your taxable account faces a big ole’ goose egg tax rate). If you’re married and file jointly, that number increases to around $80,000 – which means you can sell off $80,000 worth of gains in your taxable accounts and pay 0% in taxes.

So what does this tell me?

This tells me that I need to pivot on my current strategy a little bit, and as I get closer to early retirement, start contributing more to that emergency fund “Safety Net” account so that, by the time I retire, it’s got about $30,000 in it (instead of $18,000), which is a comfortable 12-month runway in case shit hits the fan. And because it’s under the $40,000 limit for #singles, I won’t pay any taxes on the sale + withdrawal of the capital gains and dividends.

The interest produced from bonds in the account is taxed a little bit differently; interest is taxed as earned income, rather than capital gains – but if I have no other earned income, I’m pretty sure that would put my interest withdrawals under the standard deduction amount, and therefore be tax-free as well.

The intention is that you’ll avoid using any of the principal (the amount that you contributed, and the amount you need to keep growing) in the first 5 years, and have enough in accounts like Safety Net to cover your ass if the market drops 30% and takes awhile to recover. You never want to be in a position (in the first couple years, at least) where you’re selling your equities at a loss, because that means you’re “realizing the loss,” or locking it in. If it drops and you hold on to it, it can go back up again. If you sell it to use the money, well… you’ve actually lost money.

Let’s check in really quickly

What we’ve learned so far:

-

I can retire in 7 years based on the average monthly contributions I worked with (and praying for a 6% average return), with a little over $1M – which would give me the ability to use $40,000 of gains per year, tax-free

-

I need to make sure I start adding money to that emergency fund as early retirement gets closer so that account has $30,000 in it before I leave the workforce

-

If I decide to cash out and use that emergency fund in year 1 of early retirement, I won’t pay taxes on the sale of the capital gains, because it’s under the $40,000 limit for long-term capital gains taxation when you have no other earned income – and the interest taxes should be covered by the standard deduction

What about other income?

Remember how I said I’ll probably still work in some capacity? I’m fairly confident that I’ll be able to generate at least $1,000 per month in other part-time work (teaching fitness, blogging, etc.) – work that I’d consider a “hobby,” especially since I won’t be working full-time anymore.

That decreases the amount of money I’ll have to use in retirement by $12,000 per year, give or take, which is a big help – after all, if my planned “safe withdrawal” rate is $40,000 per year from my investment accounts (thanks to the $1M of interest-generating money invested), my side hustle income would knock down my withdrawal rate to $28,000 ($40,000 minus $12,000).

That gives me a lot more wiggle room in retirement – after all, if you consider that you calculate your FI number by multiplying your annual expenses by 25 ($40,000 x 25 = $1M), $28,000 x 25 = $700,000. I’ve got about $300,000 of buffer in my number if I can generate $1,000 in monthly income.

I don’t know about you, but that makes me feel a whole hell of a lot better about my plan – if I only “need” $700,000 and have $1M, I’ll feel less stressed about market swings. This is all made possible by maintaining a little side hustle income, which will probably feel easy-peasy with no full-time job.

The only thing to note here is that having any earned income will eat up the standard deduction (in this case, $12,000 per year accounts for almost all of it), so when I think about this strategy, I think about it as providing a buffer so I can withdraw less over all – not that I’d add a hypothetical $12,000/year side hustle profit to the $40,000 I’m withdrawing and live a little large. I’d only withdraw $28,000, to stay under the 0% mark of a $40,000-per-year “income.”

Which account do you start using first?

The important logistical tidbit I learned reading Financial Freedom is that you don’t actually want to touch those investments in year 1, if you can help it – you want to give them a full year of generating interest before you start using the account. It makes sense – if $1M is the principal I need to generate enough interest to live on, then I don’t want to withdraw $40,000 in year 1 (I mean, you certainly can; the math still works out). The more conservative route makes me feel a little more comfortable, though.

More or less, in year 1, you want to live off side hustle income and that emergency fund cash (in my hypothetical case, it’d be the $1,000 per month and the $30,000 saved up in the Safety Net).

After you’ve given your investments 6 months to a year to generate some more interest, the first account you’ll start to use is your taxable investing account (in other words, the account called “General Investing” in the table above). Because this money isn’t growing tax-free or tax-deferred like the 401(k) and IRA, it’s technically the “least” valuable, from a tax perspective. Your dividends are getting taxed every year, unlike the dividends in your other retirement accounts (see why retirement accounts rock? They’re SEXY TAX SHELTERS!).

You’ll want to use this first. The other advantage to using this first? No penalties!

Based on our numbers in the chart, there will be about $736,637 in this account (and remember, that’s a high, high estimate, so use this as an intellectual exercise and not a, “Katie’s a rich bitch,” exercise, because I’m essentially projecting my two best months ever onto the next 7 years as if it’s indefinitely sustainable).

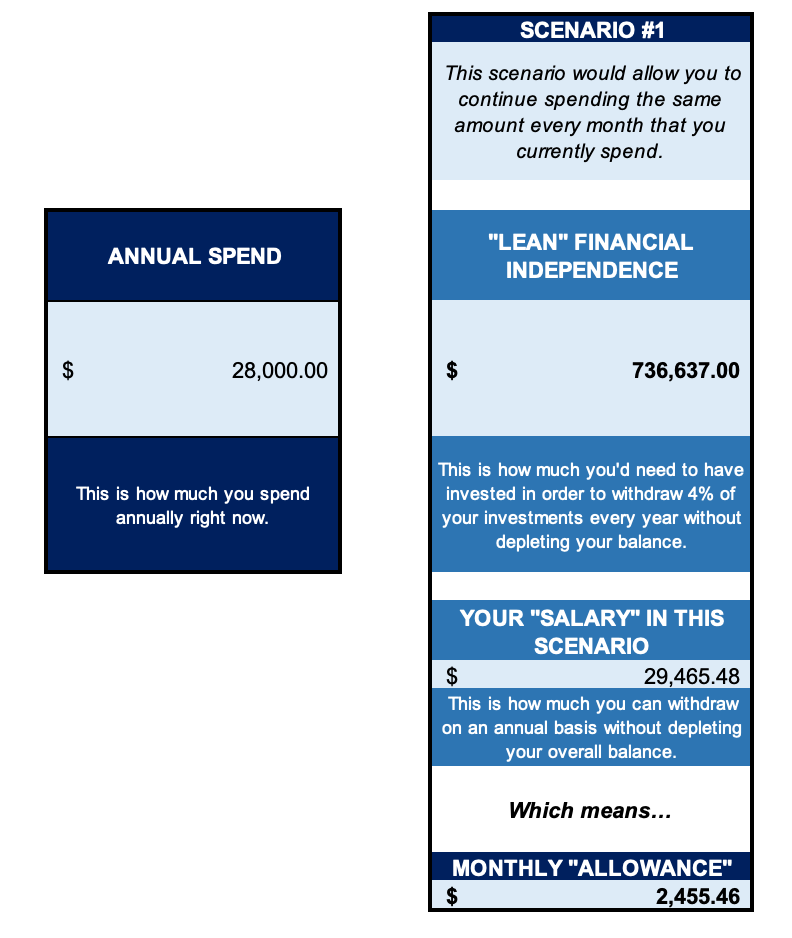

Using the Financial Independence tool on my site, I plugged in what a $28,000 withdrawal rate from this $739,000 General Investing account would do over time (in other words, how long can I live off this one account before it runs out?). I was surprised by what I saw.

You’ll notice if I withdraw $29,465 per year from this investment account worth $736,000, it’ll spit out $2,455/mo. Adding that to my $1,000 predicted side hustle income, I’d be able to spend about $3,455/mo.

The cool thing about the Financial Independence tool is that it’ll tell you when your money will run out. While it was designed to show you that your TOTAL “FI” number is enough to compound over time and still give you millions in retirement despite using some of your investment income, it’s also useful for showing you when smaller accounts will run out.

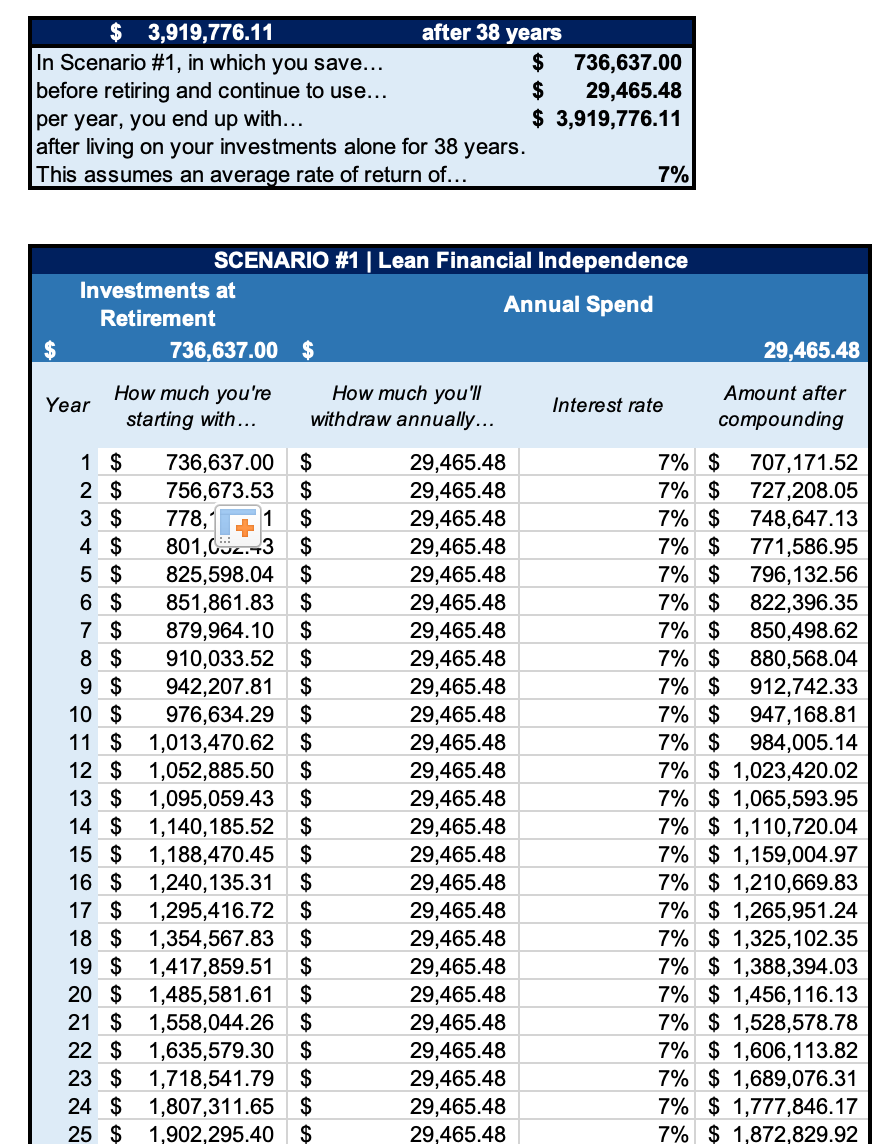

I was SHOCKED by how long this account will last me. Check out the below, where you’ll see that I could withdraw $28,000/year from this account and – if the markets constantly return 7% – the account would never run out. In fact, not only would it not run out, but it would grow to $3.9M after withdrawing $29,000 per year for 38 years.

See how the total account balance goes up over time despite using $29,000 per year?

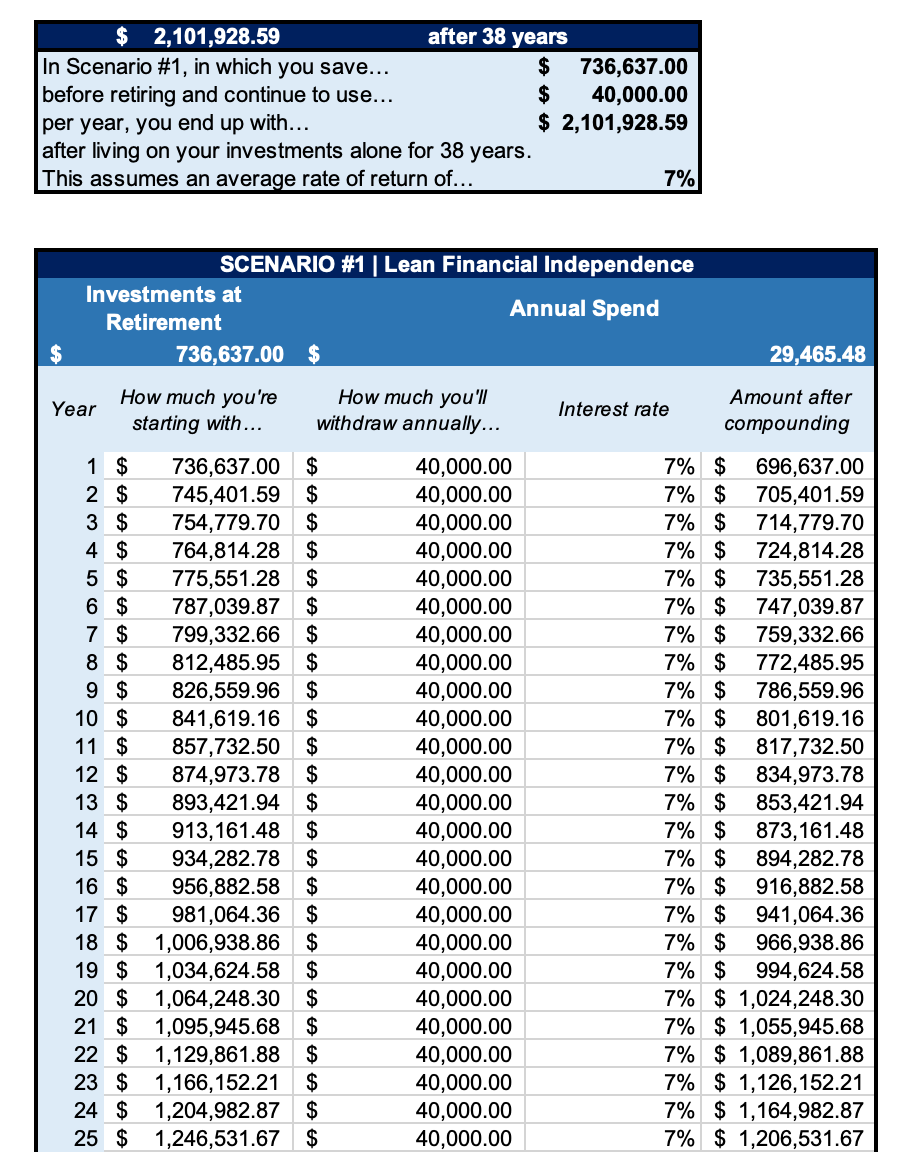

What if you did, hypothetically, withdraw the full $40,000 each year from the General Investing (taxable) account?

So let’s say you break both your legs and the internet gets canceled. No more fitness instruction or blogging for you, KG.

If I were to withdraw my full $40,000 from the General Investing account, I’d get 23 years of longevity out of this account. And since I’d keep my withdrawals under the $40,001 mark, it would all be tax-free (no long term capital gains taxes, remember?).

…it still doesn’t run out. After 38 years, withdrawing $40,000 per year, it becomes $2.1M.

Notice how using $40,000 every year slowly depletes the account, but the interest always kicks in to save the day.

But this is in the best case scenario that the 7% return is a strong average, and we all know that some years you’ll see 15% dips, not gains. While I’m thrilled with the fact that it appears one account alone will be enough thanks to a low-consumption lifestyle and the 8th wonder of the world, compound interest, I want to enact the rest of the plan to finish fleshing this out.

Because not only could a few bad years derail the goodness of this one’s longevity, but it’s also likely that it won’t be worth anywhere near $700,000 by the time I use it (thanks to the aforementioned “unsustainable income” supernova I noted above).

Let’s say that General Investing account has a few bad years and it runs out when I’m 45 or 50 (which is probably more realistic; the math shown here is basically the best case scenario).

What would I do next?

Next, you want to use your “Traditional,” pre-tax retirement accounts

In my case, that would be the 401(k) with $238,000 at the time of retirement.

In order to use this money before I turn 59.5, I’d have to do something called a Roth IRA conversion ladder, which I explain in greater detail here.

While it’s definitely worth understanding how this works, the main things to know about this are:

-

It exploits a tax loophole (that we’re hoping will still be around later in life) where you can convert your 401(k) to an IRA, and then do a Roth conversion to pay the taxes on the money. After 5 years, you can use that money penalty-free. If you keep your conversions under the standard deduction amount and have no other earned income, your conversions will be (another loophole!) tax-free.

-

You do have to pay taxes during the Roth conversion phase as though it’s income if you convert more than that, so you’ll want to plan for paying (let’s say, for rough estimates) 20% of the total conversion amount in taxes with other money. That is, money that didn’t come from the conversion itself.

Since $40,000 is the withdrawal amount, five years before my General Investing account is set to run out, I’d want to begin the Roth IRA conversion ladder: That way, when the money runs out of General Investing (which I should have a better sense for as it gets closer and we know how the #MarketMovez affect its lifetime), I’ll be on the tail-end of my 5-year waiting period to use my first 401(k) chunk of converted money.

Another #tidbit worth mentioning here is that I could always draw down these accounts in parallel to exploit the standard deduction loophole described above indefinitely. In other words, I could swear off the side hustle plan and convert $12,550 chunks (the standard deduction) of the Traditional 401(k) right away, then after 5 years begin supplementing the taxable income withdrawals with the 401(k) converted chunks.

That would be: $12,550 from the 401(k), converted to a Roth IRA and available after 5 years, + $27,450 from the taxable, General Investing account, for a total of $40,000 per year tax-free income from my accounts (again, it’s tax free because it’s <$40,000, the current upper limit for the 0% tax bracket on capital gains).

The other, OTHER thing worth noting here is that I’m assuming the “single filing” tax numbers; if you’re married, that number doubles – you can withdraw $80,000 tax-free. single tear glides down cheek

Let’s pause here and review

I retired at 33 with $1M.

I continued to generate $1,000 per month in side hustle income, but let’s say (for the sake of being conservative, remember?!) that I used $40,000 per year of my $736,000 taxable investment account called “General Investing.” In this scenario, it’s projected to last forever, but for the sake of the Coronaviruses of history, let’s say it doesn’t.

At some point, I’d take $12,550 of my 401(k), convert it to an IRA, and then perform a Roth conversion (more realistically, the standard deduction will be higher 7 years from now, but I’m using present-day, 2021 numbers).

For the sake of this example, it may be worthwhile to pick a timeframe for beginning the conversion ladder. Let’s say we choose age 45, or 19 years from now, so that the first chunk of converted funds are available at age 50.

That means we’d begin our conversion ladder in year 2040, and according to our table above, that would mean we’d have a little over $900,000 in the General Investing account by then, despite using it unabashedly for the last 19 years.

Using that approach, how long would the 401(k) last?

One amazing thing to remember: You know how we were just slowly drawing down our $730,000 General Investing account for the hypothetical period of 19 years?

For those near-20 years, all the other accounts (untouched) were growing in the background and continuing to compound.

Say it with me: Ho. Lee. Shit.

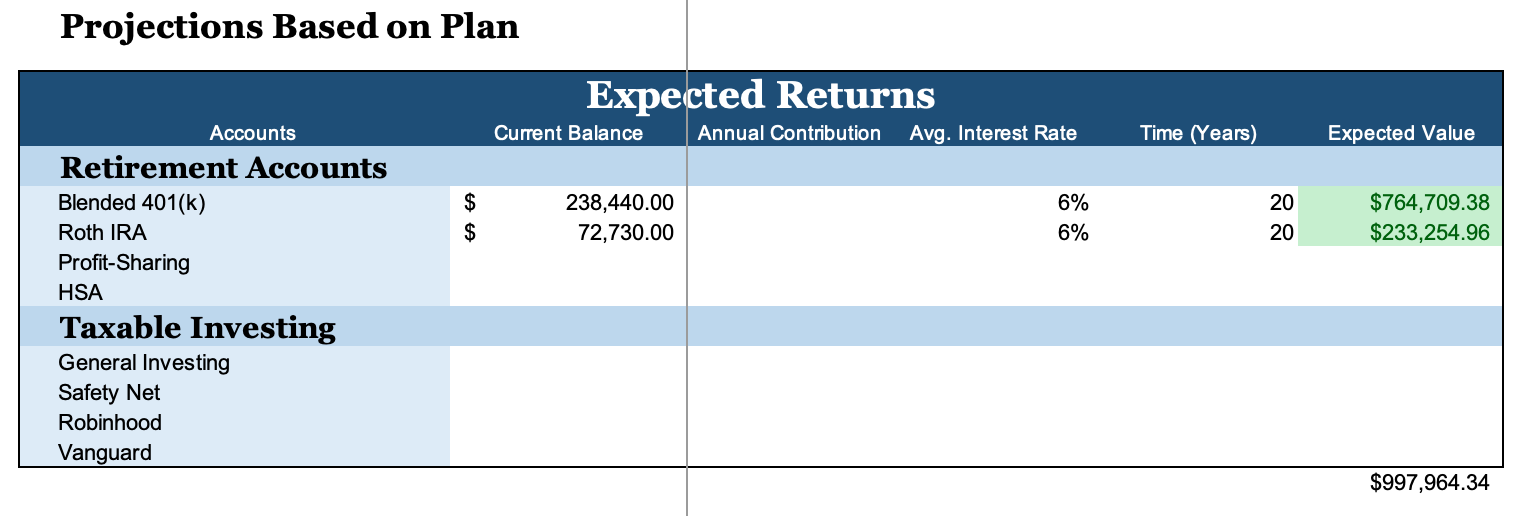

Let’s see what would’ve happened to those accounts, gone untouched, for that 20-year timespan (with no additional contributions!). Wealth Planner projections, whaddya got for me?

Holy shit – over the 20 years that these accounts were just hanging out untouched, the 401(k) grew to $764,000 on its own and the IRA grew to $233,254.

I’m going to be honest, at this point, I don’t even feel compelled to figure out “how long it would last” because the more appropriate question is, “How many millions will you leave to your heirs?”

All you need to know is, you’ll draw from the 401(k) until it’s gone and then the Roth IRA last, because the Roth money grows fastest. While there are a few strategies on the table here, I’m tempted to say totally draining the taxable account first probably makes the most sense before moving to these tax-advantaged accounts.

Roth IRAs are a great gift to your heirs, by the way, because of some other funky tax law – I think it’s because the taxes are already paid, but rules around passing down money are not my current forté (yet) because the idea of procreating at 26 makes me want to obtain a Xanax prescription.

My major takeaways after running through this exercise

I have to say, I’m a little surprised at how well this plan worked out. I was skeptical (nervous, even) that when I sat down to flesh out the details, I’d find that my plan was screwed.

Of course, there are some other assumptions happening in the background as well, beyond a consistent 6% return – that I’ll always get an employer match, that my expenses won’t increase beyond $3,333 ($4,333 if you include the presumed side hustle income) per month, etc., and that there won’t be any catastrophic, world-as-we-know-it-ending event that permanently derails the stock market forever (but honestly, if that happens, I’ll have bigger problems than my early retirement dreams going down the tubes).

We also ignored the impact of taxes on dividends year-over-year in the taxable account, which would’ve accelerated that draw-down.

But even then – with all these things taken into consideration – this plan worked out to where it looks as though I’d have millions LEFT OVER after I bite the dust, which makes me feel pretty confident that a few of these things could go awry and I’d still have more than enough to last me.

In summary, when preparing for early retirement

-

Save 12 months of expenses as an emergency fund before you retire (rather than just 6) so you’ve got a cushion from bad market returns.

-

Use the taxable account first, and supplement with side hustle income if you can or feel like it (if you’re able to work hard enough to earn enough to retire at age 33, you’re probably not going to be able to prevent yourself from earning a little).

-

Use the Traditional retirement accounts next, using the Roth IRA conversion ladder to bridge the gap between your age when the taxable account runs out and age 59.5 (depending on how much you save in the taxable account and how much you actually withdraw every year, this could be a pretty small window).

-

Use the Roth accounts last, as they grow the fastest (growing tax-free and coming out tax-free).

Things that I’m still unsure about

-

How much do I need to factor in for monthly healthcare costs, especially as I age? How will that increase my number?

-

How will I plan for the taxes I’ll need to pay as I convert my Traditional retirement money to post-tax money if I end up going above the standard deduction? Is there a really efficient way to do this other than, “I’m sure there will be some leftover every year,”?

With more sophisticated calculators, I could probably account for some of these things. But for now, I’m feeling A-okay about this plan.

And if you use the tools screenshotted (screenshat?) above, you can more or less project out your own path, too.

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time