Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

For a few hours on the Fourth of July, I did the most patriotic thing I could imagine: joining local Safeway workers on the picket line as they continued a sweaty, weeks-long strike to protest unfair labor practices. The company had been using illegal bargaining tactics (“surveilling, threatening”) during contract negotiations, and the union—UFCW Local 7, which represents more than 23,000 food and agriculture workers in Colorado and Wyoming—was determined to force better behavior.

The first picket lines germinated at a handful of Colorado stores on June 15, mushrooming to new locations with each passing day. By July, workers at more than 45 stores were on strike, some picketing all night. The company had to import expensive contract labor (“scabs”) from other states to keep shelves stocked.

When I pulled up to the first store, situated across the street from a Porsche dealership and dental implant center, the parking lot looked unusually barren. As I got closer, I noticed the front windows had been boarded. I approached a cluster of people standing next to the sliding doors with lettered signs hanging around their necks. “They just came and shut this one down,” a young gas station attendant named Christopher told me, “but we’re holding the line.” Beside him stood a longtime cashier named Velma. Together, they told me what was at stake: The company was considering halving the pensions for the 30- and 40-year store veterans, removing a guarantee that part-time workers would get to work for at least 20 hours per week, and, worst of all, cutting healthcare. Their frustration was palpable. So was their loyalty. “My mom’s got 46 years at her store,” Christopher noted proudly.

The temporary closure of the first store represented a union win, sending a message in the only language corporations understand: loss of revenue. I moved on to the next location, a much livelier, active strike with dozens of picketers packed densely across the store’s sun-bleached expanse. Some customers who walked past sheepishly averted their eyes (“Sorry, guys, there’s a sale on soda”); others read the signs (“PLEASE DO NOT PATRONIZE SAFEWAY”) and ceremoniously announced, to whoops and cheers, their decision to shop elsewhere in solidarity. A much smaller percentage, bewilderingly, antagonized with expletives and middle fingers—one patron, presumably intoxicated from holiday festivities, stumbled toward his car and then wheeled around and began shouting incoherently. I only picked up a few words from across the parking lot: something about work ethic, handouts, and “striving.”

After about an hour, I met Anthony, a middle-aged man with a wide grin who started working at Safeway before the pandemic introduced us to the concept of “an essential worker.” When I asked him the same question I had posed to Christopher and Velma, he reiterated their concerns and shared his own—how quickly food prices had been rising for his customers, who he felt responsible for protecting. “In just the last few years, the prices have jumped like crazy,” he said, adding quickly, as if to make it clear employee greed wasn’t to blame, “and we haven’t seen a dollar of that.”

A receipt tracker compared 2022 Safeway receipts to 2019 receipts for the same items and found the company’s prices rose a stunning 76%, outpacing overall food inflation nearly sixfold. Founded in 1915 and commandeered by the private equity firm Cerberus since 2006, Safeway’s recent history is checkered with failed mergers, delayed IPOs, and—as anyone who’s shopped there can attest—staggeringly high prices. (They boast 27% gross margins, compared to Kroger’s 22% and Costco’s 13%.)

After decades of mergers and acquisitions, the US grocery industry—which employs around 2.6 million Americans—is an oligopoly. Safeway, one of 22 chains owned by parent company Albertsons, is a portrait-in-miniature of this trend. In coverage of the proposed 2022 Kroger-Albertsons merger, antitrust journalist Matt Stoller wrote, “There are already 30% fewer grocery stores than a few decades ago and most major metropolitan areas…are heavily concentrated among just a handful of grocery chains. That means large chains not only secure better prices for goods than their smaller counterparts, but can also increase prices faster than costs, contributing to inflation.” At the end of last year, the FTC blocked the Kroger-Albertsons merger in a rare antitrust coup, taking the position that the two grocery behemoths needed to “continue to compete for workers through higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions.”

A mutating syndicate of private equity firms still owns large swaths of the now-publicly traded Safeway, with Cerberus at the head (fittingly, “Cerberus” in Greek mythology is the three-headed dog that guards the gates of hell). Over their uncharacteristically long tenure, they executed the standard-issue PE playbook: selling the company’s real estate for an infusion of cash just to lease it all back, assessing onerous management fees, and, of course, saddling the stores with the billions in debt necessary to grease the wheels of High Finance. As is customary, the firm used Safeway’s assets as collateral to borrow the money they needed to buy it, after which they could use the grocer’s operating cash flow to pay the interest on the debt. Between 2013 and 2018 alone, Cerberus reportedly charged $350 million in (debt-financed) fees. As The Onion so eloquently put it:

Earlier that morning about 1,600 miles east of Denver, President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act into law. One of its most unpopular features is a new administrative hurdle for Medicaid users, which would require them to frequently requalify for coverage by proving they’re always working at least 80 hours per month (conveniently, this cost-savings portion of the law wouldn’t take effect until 2027, delaying the pain until safely after the midterms). When Christopher told me about the “20 hours per week” guarantee being rolled back, I came face to face with the cruel truth that Matt Bruenig highlighted in his piece about the idiosyncrasy of Medicaid work requirements: It is employers, not employees, who control things like hours and scheduling.

Much of the discourse around the legislation has—rightly—emphasized all the ways in which poor, working-class, and rural Americans have been sold out. The average critic might analogize the country to an airplane where the First Class cabin keeps siphoning snacks and square footage from Basic Economy. But this elides an even more humiliating reality: It’s more akin to auctioning off the fuel and engine fan blades to subsidize cushier seats for the 12 folks upfront. Sure, they might be incrementally better off for a little while, but the tradeoff will look pretty stupid when you sell off one too many parts and the whole plane goes down. Unfeeling legislation in service of sound economic policy is one thing—a bitter pill for a healthier future—but it is another thing entirely when the underlying mechanics more closely resemble the dwindling final hours of a coke-addled bender.

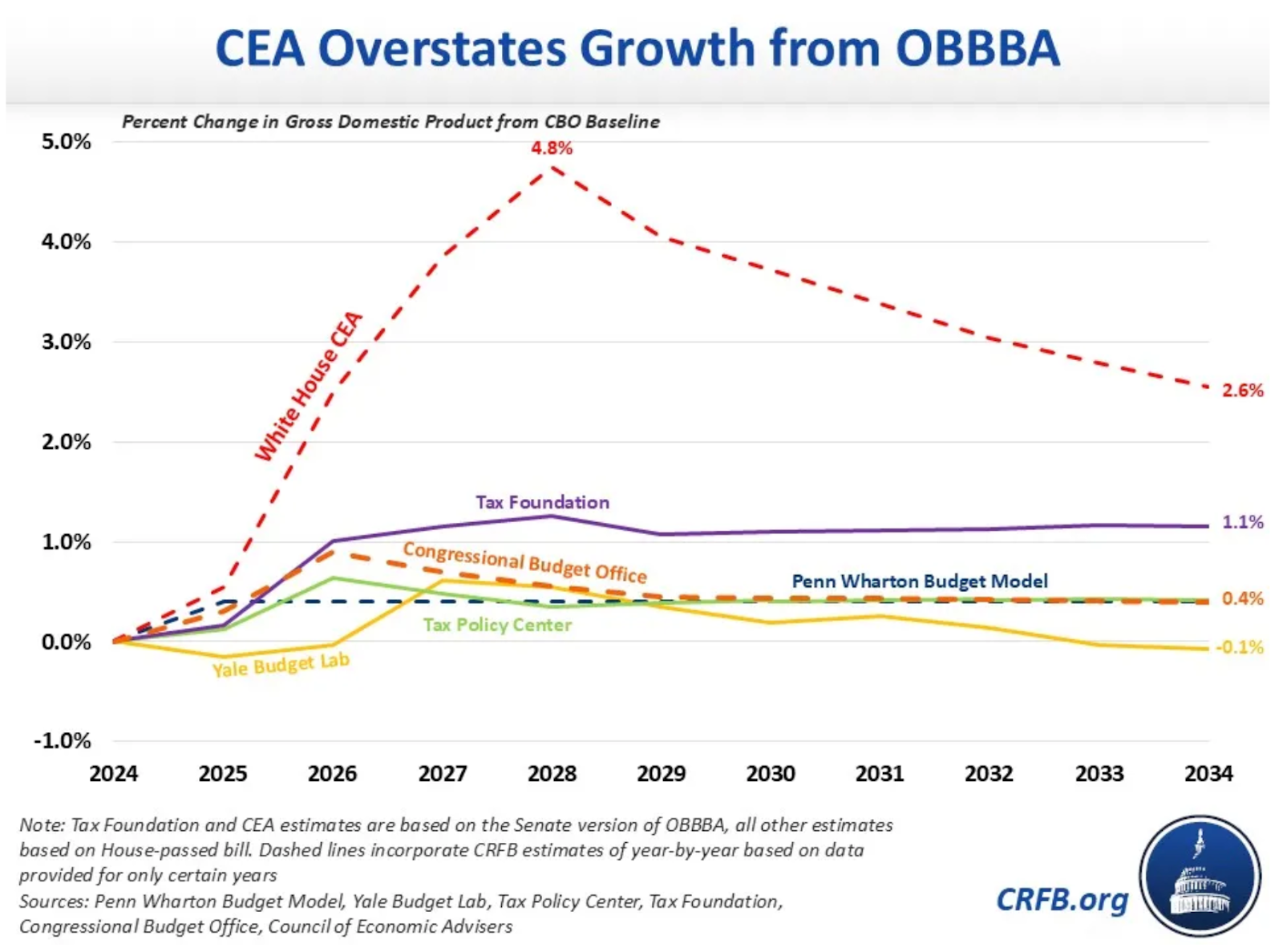

You have to hand it to Congress: If nothing else, the legislation is a tonal match for the private sector of our economy, where you’ll find financial parasites transforming one of America’s largest grocery store chains into a host organism, deploying “gratuitous layoffs and price hikes” to feed the junk debt required to wear it like a skin suit. The Congressional Budget Office’s dynamic estimate—the most generous projection, as it takes economic growth into account—expects the legislation to add, conservatively, $2.8 trillion to the federal deficit by 2034. While some modest growth is anticipated from extending existing tax law, every credible independent analysis (save for the White House’s own fantasy projection) warns it will be dwarfed by the costs of borrowing to make up for all the lost revenue as we mortgage our collective future at six percent.

Deficit spending that makes a direct investment in productive capacity—say, investing in the care, health, and education of our nation’s children, as opposed to, I don’t know, slashing the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—is like taking on debt to buy a cash-flowing asset. An initial outlay of borrowed money is a strategic way to create long-term gains based on real value creation. But deficit spending for another round of tax cuts is more like getting blackout drunk on bottom-shelf tequila sunrises and heading to Neiman Marcus with your AmEx superglued to your forehead, praying that when you come to, you’ll have purchased a few items that retain resale value at least until the bill comes due.

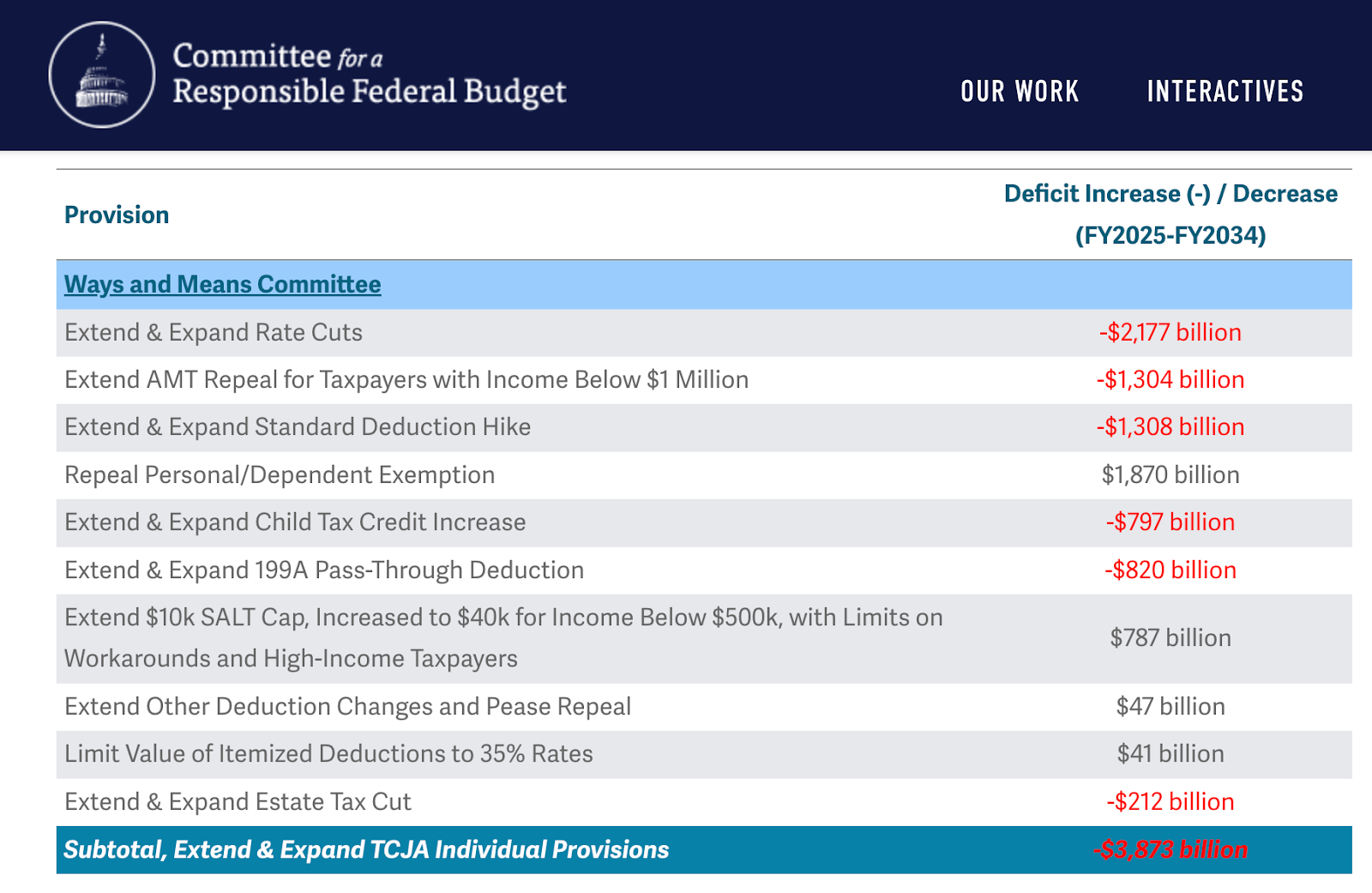

To say this legislation is designed to disproportionately benefit the Americans who need it least is an understatement. To quickly understand why, consider its most expensive components:

The largest expense is the approximately $2.2 trillion allocated to extend the tax brackets introduced in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Of that $2.2 trillion, $1.1 trillion—fully half—is just the cost for the 1% of Americans who earn more than $500,000 per year. It only gets more egregious as you scale the income distribution ladder into the rarefied air of seven-figure incomes: More money will flow to the 1.2 million Americans who earn $1 million or more per year than the bottom 127 million Americans combined—those who earn $100,000 or less.

The second-most expensive component, at $1.3 trillion, is extending the repeal of the alternative minimum tax. Established in 1969, writes the investment firm Charles Schwab, the alternative minimum tax was “devised to target a small number of very wealthy taxpayers” who avoided paying their share by “exploiting tax loopholes.” Prior to the passage of the TCJA in 2017, only 3.1% of households were impacted. Under the current legislation, this number shrinks to fewer than 0.1%—which means a $1.3 trillion loss of revenue benefits only the 3% of loophole-happy households who would’ve otherwise triggered it.

It shouldn’t be controversial to say that income tax cuts primarily benefit high earners, for one obvious reason: Most low- and middle-income people pay relatively little of the federal income tax to begin with. In 2021, the top 1% paid 45.8% of all income taxes; the top 10% of earners, or those earning more than $169,800, paid 75.8% of all federal income tax. The bottom 50% of earners accounted for only 2.3% of total revenue, a fact less reflective of their contributions than how little money they received for those contributions to begin with.

This is an argument that gets trotted out to refute the idea that the rich “aren’t paying taxes,” but it works equally well as proof that tax cuts—by definition—can’t really benefit the middle and working classes in the same way they benefit high earners. So why do it? The persistent myth that making rich people incrementally richer will unleash feverish economic growth is a fantasy plucked directly from Milton Friedman’s wettest dream: In a landmark 2020 paper, a team led by London School of Economics researcher Dr. David Hope studied the economic effects of major tax cuts in 18 wealthy nations over 50 years. Their conclusion shook the leaders of the high-income world and surprised approximately nobody else: “The rich got richer and there was no meaningful effect on unemployment or economic growth.”

When they published their findings, they were—and I quote Dr. Hope directly here—“accused of being socialists.” He recalled how the strongest negative reaction came from Americans, who have not only enshrined a commitment to the debunked logic of trickle-down economics into law many times over, but ritualized it culturally, believing the world functions best when you have a few brilliant individuals at the helm and the rest of us along for the ride, content to huff the fumes of elite farts. Economic journalist Paul Krugman calls the fear that raising taxes at the top will stunt investment, innovation, or growth a “zombie economic doctrine” that “should be dead in the face of vast amounts of contrary evidence,” but persists for one simple reason: It behooves those in power for the rest of us to believe it.

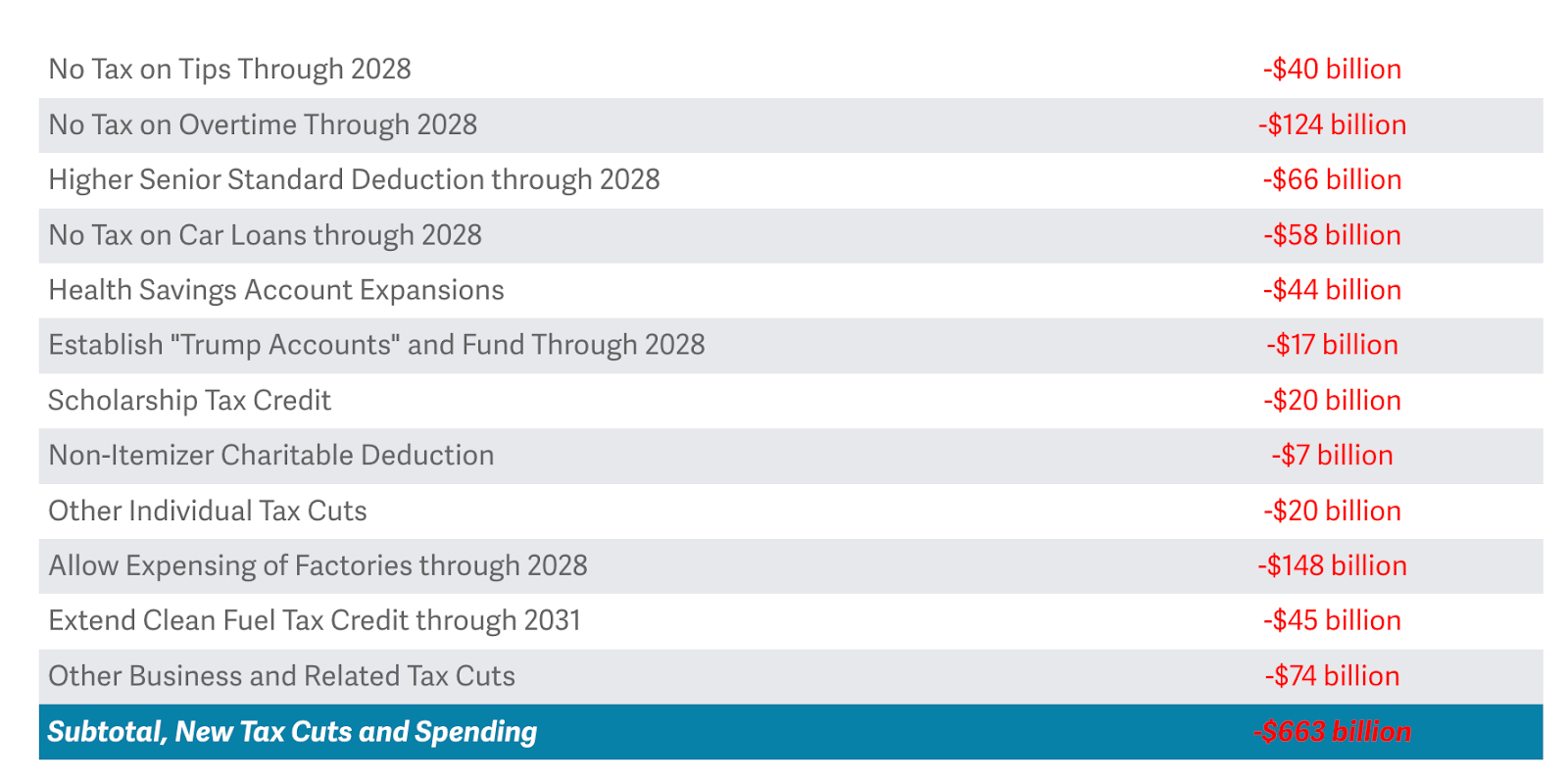

As far as the provisions that could theoretically be construed as “for normal people” with a straight face, it’s a matter of proportion. While the aforementioned tax cuts are permanent, the majority of the more targeted relief measures expire after 2028. As a result, they make up a relatively paltry portion of the overall legislation:

Take, for instance, the widely publicized and celebrated “no tax on tips” and “no tax on overtime.” Reading the fine print, you’ll learn it’s only the first $25,000 of tips and $12,500 of overtime that are deductible for certain occupations, as long as you earn less than $150,000 per year. Together, these two measures cost just $164 billion. For context: At least 15x as much money is allocated to households earning more than $500,000. The promised soundbite of “no tax on Social Security” was diluted to a relatively inconsequential $6,000 bonus deduction for retirees over 65, which will—you guessed it—expire after just three years.

When it comes to authentic fiscal conservatism, I’m empathetic to the argument that the federal government has “a spending problem, not an income problem.” Many Americans don’t feel as though they receive anything for their federal taxes. This is partially because our defense budget is more than four times as large as the next-largest military, and the government’s relationship with defense contractors mirrors that of another high-spending area, our healthcare “system.” The Medicaid and Medicare programs are critical, but Medicare especially tends to function like a backdoor subsidy racket for private equity-owned hospital chains and companies like UnitedHealth Group. This dynamic badly needs to be reformed.

But reforming it, we aren’t! On the contrary, much of the underlying private-public enmeshment that funnels public funds back to the shareholder class is being left untouched. Much like a private equity firm, we’re simply borrowing the money to turn around and channel it upward—and removing health insurance for somewhere between 10–17 million Americans in the process, the economic costs of which will realistically be punted to employers, providers, and insured patients.

The only difference between the suits at Cerberus and the raiders who passed this legislation is that the latter are elected representatives who should ostensibly know better than to dropkick the can down the road yet again. We are rapidly running out of things to plunder.

When I woke up the next morning, I checked the Denver DSA Instagram—the organization that supports local labor organizing, among other things—and saw the union had reached an agreement with the company. The strike was over. Their healthcare and pensions were safe for another contract cycle, and the union president had even managed to negotiate a wage increase.

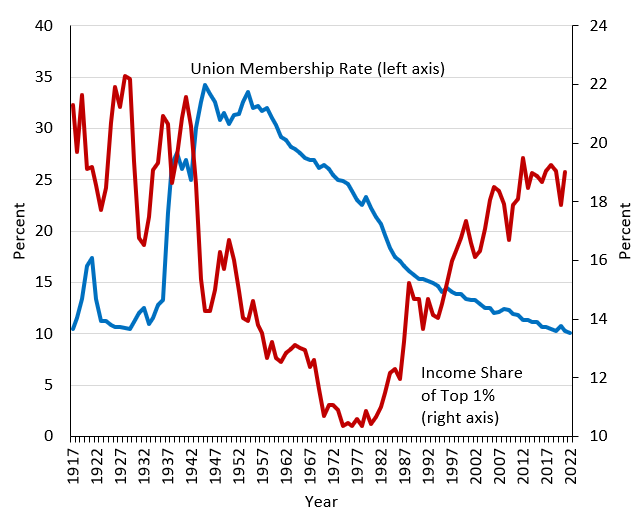

Playing collective hardball was common during the periods of American history most associated with a strong, prosperous middle class, times when both union membership and marginal tax rates were high. In another recent analysis, Krugman spun through the most popular narratives for increasing inequality: globalization, technology, and financialization, to name a few, each of which played a role. Ultimately, he stuck the landing on the thin edge of Occam’s razor: Wages are “less determined by the invisible hand of the market and more by the visible hands of workers and employers bargaining hard,” he wrote. Put another way, economic outcomes are determined by the distribution of power. In the mid-1970s, a quarter of the population negotiated their pay and working conditions as a bloc that could threaten to withhold their labor en masse. (This environment caused wages to rise for non-union workers, too.)

As the government became friendlier to corporations and tacitly endorsed more aggressive labor-busting practices over the following 50 years, union membership steadily declined and the 1%’s share of total income nearly doubled. As of 2024, fewer than 10% of workers bargain collectively.

There is no single person or institution capable of steering the ship away from the iceberg—no brilliant billionaire, no strongman president fighting for the red or blue team. Prosperous eras of American history were not the result of a benevolent demagogue or a more egalitarian cultural spirit, but a realistic understanding of how leverage works in a market economy. Scrolling through the comments on the union’s announcement that an agreement had been reached, one phrase appeared over and over again: “When we fight, we win.”

As the quantitative reality of “the 1%” reveals, there are many more of the metaphoric “us” than the metaphoric “them.” While rhetorically powerful, I fear this undersells the situation: There is, ultimately, only “us.” Because whether the economic, fiscal, or climate bill comes due first, one thing is for sure: We will all be forced to pay it.

July 7, 2025

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time