Why Leasing a Car is Like Setting Money on Fire [2025]

April 7, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

2025 Update: In 2022, we invited a pro-leasing guest on the show to discuss how, when, and why leasing a vehicle might make sense. Enjoy!

Because I spent the morning getting my car appraised at CarMax like the good money blogger I am, it felt like the perfect day to sit down and write this post.

I get asked about leasing a car probably once a week, and it still surprises me that so many people opt to rent a depreciating asset – it’s one of those things where I think we (read: Americans) have a fundamentally distorted understanding of just how bad it is for us. (Coming from the people who invented the Baconator and all-you-can-eat shrimp at Popeyes? Shock and awe!)

Sure, buying a depreciating asset isn’t much better, but we’ll circle back to that shortly.

For the record, I used to have a lease – and when my lease was up, I bought a used Audi A3 and chronicled the experience of marching into car dealerships and negotiating with grown men by myself. It was time-consuming and stressful.

Today, less than a year later, I’m selling that car so we can be a one-car family – not because I don’t love the car, but because I realized that I had no idea what was in store for me over the next 12 months when I bought it this time last year.

Beyond that, I noticed in my 2020 annual spending report (yes, that’s really a thing that I do – I call myself CFO of Money with Katie for a reason) that I had spent nearly $6,000 over the course of the year on my car: the payments, the insurance, the gas, the maintenance – shit really added up, and I didn’t feel like I got $6,000 worth of value from the vehicle that sat mostly unused as I worked in my living room to make the $6,000 that paid for it.

I bought the car as a 20-something who figured she’d spend the next 10 years of her life driving to and from work every day in sunny Dallas, Texas.

I’m selling the car today as a 20-something who’s moving to snowy Colorado in a month to work from home and live in a town that’s almost entirely navigable by bike.

It no longer makes sense for me to own a car, let alone a spunky red jellybean with front-wheel drive.

But what if it does make sense for you to have a car? For most Americans with a commute that can’t be made by foot or public transit, a car is a necessity – so how did we get it so wrong?

I’ve written about why cars are such a drain on us financially in the past (usually, it’s the most expensive thing we buy besides a home, and we treat the decision as if it’s inevitable; then, the expensive hunk of metal has the audacity to rapidly lose all of its value over the next 10-15 years). But sure, let’s patronize Chevy Truck Month!

Today, I want to talk about why leasing specifically is so horrific financially.

Let’s revisit the whole “depreciating asset” thing

“Depreciating asset” is code for “expensive thing that eventually becomes worthless over time.”

Cars are about as “depreciating asset-y” as it gets.

You’ve probably heard the phrase, “A car starts losing value the moment you drive it off the lot,” but I want to pull in some anecdotal evidence of this to make it real with regards to leasing.

When I bought my car in 2020 (the same one I got appraised to sell today), I paid $19,500 for it – the MSRP new? $36,000.

The car was three years old, and its previous “owner” was a woman who leased the vehicle brand new. That means she made payments on a car that was “valued” at $36,000, and just three years later, it was worth less than $20,000. In the first three years, it had lost nearly half its retail value.

If she put $1,000 down for a lease on a $36,000 car and got a lending rate of 2%, that means her monthly lease payment was likely around $500 for three years. The person who leased my car before I bought it likely spent:

$1,000 down

$500/mo. for three years, or $18,000

= $19,000 total for the pleasure of renting a car that I purchased for indefinite use just three years later for $19,500

While this example might be a little extreme (since it depends a lot on what the car’s “agreed upon” value was at the end of her lease term), we can make some assumptions based on the fact they sold it to me for $19,500.

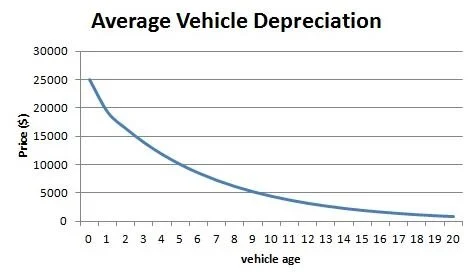

You can picture a depreciation curve a little bit like this:

When you lease a car, you’re paying for the steepest depreciation hit – and then giving it back.

You’ll notice around year 10 the value of the car starts to bottom out a little bit; this is why, if you’re going to buy a car, buying a car that’s a few years old and will last at least 10 more is one of the best ways to mitigate the utter thrashing you’ll take by buying it new or leasing it.

But look, I get it

I do! I’m not going to sit here and tell you that it’s easy to buy a 14-year-old used Honda Accord for $5,000 cash and move on with your life, especially if you work hard and make a lot of money. There’s that sneaky, “I work so hard, and spend so much time in my car!” feeling that I know most of us are familiar with (especially if you work in an office) that pairs with the intoxicating scent of new car smell on the showroom floor and – when they throw that low lease rate at you – it’s easy to get swept up in ‘how you’re getting such a great deal!’

The trick almost worked on me when I went to turn in my leased Acura RDX. They had me sit in a new one, “just to look at the features,” and for a split second, I almost caved. But then I remembered my goals.

We often justify spending a lot of money on a car (or leasing a nicer one than we can afford) because we work hard or have a long commute – but when you rent or buy a depreciating asset that’s more expensive than necessary, you’re guaranteeing that you have to work longer. You have to commute MORE, because now you have to pay for your expensive depreciating asset!

The worst part, maybe, is that at the end, you don’t even get to keep it – you pay for an asset during its most rapid depreciation phase, then give it back. Cars can be a slightly less horrible use of money if you’re able to pay your car off and drive it for many years without a car payment, but leasing is the exact opposite of that approach: You rent it at its most expensive, then give it back and move on.

(You might be wondering about the difference between renting a home and renting a car: The difference, really, is that buying a home entails a lot of not-insignificant costs beyond that of renting, which can make the ‘rent vs. buy’ equation more complicated. Cars, on the other hand, aren’t cheaper to lease than to outright buy in the long run, because there aren’t loads of other costs associated with owning a car that aren’t associated with leasing one, as with home ownership where you’re paying taxes, insurance, and maintenance fees year over year that renters don’t pay.)

I broke down the true cost of car ownership in the post Why You Need to Sell Your Car – Maybe (and feel pretty good that I’m actually taking my own advice now). To spare you the reading time, buying a cheap car outright and driving it into the ground for 10 years (and investing your would-be $500 car payment) nets you an extra $750,000 by the time you’re 55. That’s just ten years of foregoing the fancy lease.

Remember, you can leave traditional work once your investments = 25x your annual expenses

If you’re paying for a car (let’s say it’s a $500 per month payment and $150 per month in insurance), you’re paying $7,800 per year for your car. In order to keep up that habit forever (leasing a car that’s $500 per month), you’d need to have an additional $195,000 invested to retire ($7,800 * 25).

So not only does it slow you down on your journey to freedom thanks to the opportunity cost of your payments, but it actually moves your target further away.

It kinda makes “I work hard” a silly reason to lease (or buy) a fancy car – since it guarantees you’ll have to keep working hard.

It’s like that meme: “I drive in my expensive car to my job that I have to work in order to afford the expensive car so that the home I just bought can sit empty all day while I work to make the payments on it.” Shit is so BACKWARDS when you think about it.

The breakdown of a better way

Better might be subjective, but my definition of “better” is simply less financially wasteful:

-

The best: Structure your life in such a way that you either don’t need a car, or can get away with having one car for the family. While it’s certainly not easy due to the way most American cities are structured, if you’re able to live in walking or biking distance to your work and the other places you go, it might actually be doable – especially in the age of remote work. Even dropping from two cars to one can be a huge improvement financially, without disrupting your daily life all that much. Most cars sit parked and unused for 90% of the time you own them anyway.

-

The better: Buy a used Toyota or Honda (car brands known for lasting at least 200,000 miles and requiring very few, inexpensive repairs) or, if you’re going the luxury route, a three-year-old Certified Pre-Owned vehicle outright without taking out a loan (or taking out a small loan, if you can get a really low interest rate).

-

The meh: Buying a used [insert any other type of car here] and taking out a big loan (read: what I did with the Audi, buying an expensive German car that was cheaper because it was three years old and taking out a loan for $16,000 to pay for it over time).

-

The worse: Buying a new car of … really any kind, since new cars are just inherently terrible values.

-

The worst: Leasing a new car of … really any kind, since leases mean you’re renting a depreciating asset and paying for it during its most quickly depreciating years.

Coming from someone who jumped from doing “the worst” to “the meh” and will now be cruising into “the better” or “best,” I can tell you I already feel infinitely more relief knowing I’ll no longer be on the hook for a vehicle. Cars are stressful. The tires get nails in them, the oil has to be changed, insurance has to be renewed, the check engine light comes on… the list goes on. It’s a headache, and I’m thrilled to be in a position where I may get to be car-less for a few years.

And at least owning an inexpensive car means those headaches are slightly less expensive. I got a dent in my rear passenger-side door and I took it to the shop for an estimate – “Oh, $4,000. Minimum. You need a new door, and we need to have it shipped in from Germany. Then we have to repaint the entire right side of the car. Oh, and…” I feel like a Honda dealership would’ve just popped out the dent and sent me on my way.

I know it worked out well that I won’t need a car where I’m moving, but that was somewhat by design: We visited the town, figured out where our most likely “frequent spots” will be, and applied for homes and townhomes that were in biking distance. Remote work is easier to find than ever now, so if you work in an office and don’t want to, consider that you aren’t necessarily stuck unless your job requires you to be there in-person and there’s absolutely no chance of you applying for and getting remote work elsewhere.

Final thoughts

Sometimes our lifestyles require us to have a car – there’s just no way around it, and that’s okay. But the type of car you buy and the way in which you buy it can make a humongous difference over the long term, to the tune of shaving years off your retirement timeline and buying back your freedom.

It’s not about always making the perfect decision and denying yourself luxuries at every turn – it’s just about making a slightly better choice that has outsized rewards as it compounds over time. And more than that, it’s about recognizing that the type of car you drive truly has so little bearing on your happiness, even if you spend a decent amount of time in it.

As long as it gets you where you’re going safely and moderately comfortably, you probably won’t get an extra $20,000 of value for leasing a car that’s worth $20,000 more than the one you can actually afford.

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time