Will You be in a Higher Tax Bracket in Retirement? Maybe, But It’s Unlikely

February 7, 2022

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

A more robust version of this analysis is available in Chapter 6 of Rich Girl Nation, “Don’t Outlive Your Assets.”

Any time I open the “Roth vs. Traditional 401(k)” can of worms, I’m inevitably met with one resounding piece of pushback:

“But what if I’m in a higher tax bracket in retirement?”

This is the predominant argument in favor of going all in on all Roth: That (somehow) we’re all going to be spending more in our golden years than we’re earning now in our careers.

Today, I’m going to argue something very simple: It’s almost impossible for that to be the case, and I’ll show you why.

Usually, this question is the result of three (very different) belief systems and circumstances:

-

Those who don’t yet understand how their tax bracket is determined in retirement (I’ve talked to an astounding number of people who believe their last working salary determines their tax rate for the rest of their life)

-

Those who are unreasonably optimistic about their future returns but haven’t actually sat down to project the numbers

-

Those who are in a very low marginal tax bracket today, like 10% or 12%, but have a reasonable belief that they will spend in a way in retirement that will eclipse this (this is really the only mathematically sound rebuttal, as you’ll see shortly)

So let’s start with the foundation: How your money is taxed in retirement.

Before we dive headfirst into this rabbit hole, I want to state something explicitly: Any time we’re running loose projections for decades into the future, they become nearly meaningless because – as we extend our timeline – we extend our chances that some crazy bullshit could happen. That said, conceptually, I think this exercise is helpful, and I don’t think we should throw in the towel on trying to understand our best move just because we’re ‘planning’ for something that’s pretty far into the future.

How your money is taxed in retirement

Throughout your working life, you’re probably accustomed to the IRS coming with a hatchet for your earned income. Your noble benefactor (Corporate America) agrees to pay you $60,000 per year in exchange for 2,000 hours of your life, and you humbly agree.

Then, Uncle Sam skims his chunk off the top, and you take your tax haircut and go on your merry way.

(Your federal “tax haircut” on $60,000 is $9,806 in 2025, for the record.)

But your money in retirement isn’t based on what you earn, because you’re (theoretically!) not earning anything. This is where the folks who own 412 rental properties and mega-pensions will “BUT!” the shit out of this article, but stick with me. For most, retirement income is taxed based on something else:

What you spend.

You’re taxed in retirement based on what you spend, not on what you earn

Technically, your only “income” comes in the form of withdrawals from your own retirement and brokerage accounts. Theoretically, you won’t be withdrawing more than you need to spend (because there’d be no point to take the money out otherwise).

Of course, if you work for a really long time and make a lot of money, it’s possible your social security payouts will be decent – but that’s hard to project from our vantage points now, 40 years away.

Some of these accounts (like your trusty Traditional 401(k) steed) are taxed like income, while others are taxed in a more favorable capital gains tax bracket (the taxable brokerage account).

It’s likely you’ll pay 0% tax on your long term capital gains on some or all of your withdrawals from your taxable account, thanks to the way the brackets are set up. (Some will argue that the 0% bracket might be hacked away; to that, I say, it’s probably a futile effort to plan based on speculation around the tax code 40 years from now.)

But before we digress too far from the original point: You’ll only be taxed more in retirement if you’re spending more than you’re earning now.

If you’re like, “Oh, I only make $80,000 now, but I plan to live an LLL in retirement: A Large, Lavish Life, baby!” Let’s pump the brakes, L^3.

This is the perfect segue to addressing the second piece of pushback: that you’re going to (somehow) be able to afford a crazy luxurious life in retirement that thrusts you into a higher tax bracket.

Why you probably won’t be in a higher tax bracket in retirement

It all comes down to this very simple truth:

In order to have enough money in retirement to live large, you have to invest a shit ton of money.

Why? Because the only way to grow a humongous nest egg (one that’s capable of spinning off large sums of cash in returns annually) is to fill it with a shit ton of cash, and preferably early in life so it has time to compound parabolically (which isn’t impossible, to be sure, but certainly on the ‘unlikely’ side of average when you consider that most people hit their peak earning years between 35 and 44).

And in order to invest a shit ton of money, you have to make a shit ton of money (either that, or work for a full 40 years).

And what’s true about people who make a shit ton of money?

They’re in a high tax bracket.

The paradox is this: If you’re in a lower tax bracket now, the only way for you to be in a higher tax bracket in retirement is by spending a ton of money after you retire – but you won’t have a ton of money to spend unless you’re earning (and investing) a lot now. And if you’re earning (and investing) a lot now, you’re likely already in a tax bracket that you’ll have a hard time eclipsing with spending later.

(Either that, or living on very, very little and investing the healthy majority of an average salary – and at that rate, behaviorally speaking, it’s unlikely you’d even want to flip the switch in your golden years and suddenly change your entire lifestyle.)

Does your head hurt? Cool. Let’s add some numbers – that’ll help!

The reality of using your 401(k) in retirement

The sad reality is that it’s going to prove nearly impossible to retire on only a 401(k). If someone contributed the maximum ($23,500 in today’s dollars, adjusted for inflation every year) to a 401(k) for 25 full years – it only results in ~$1.6M, assuming average 7% annual returns.

$1.6M sounds like a shit ton of money, but after 25 years, the purchasing power of those #dollarz will be a shadow of their former selves.

To give you a sense of just how shadow-y, the equivalent purchasing power of spending $50,000 today will cost $128,000 in 25 years from now, assuming 3% average annual inflation.

Put another way: To live the same type of life that $50,000 buys you today, you’d need $128,000.

Since the widely accepted safe withdrawal rate is 4%, in order to support $128,000 in spending money per year, you’d need ($128,000 * 25) $3.2M.

There are two (obviously) shitty things about this reality:

-

Most people are not contributing the maximum to their 401(k), and for most Americans, that’s the only account they’re contributing to.

-

Most people are concerned about paying too much in taxes when they’re in retirement or “being in a higher tax bracket,” but the reality is that many of us will not be able to afford to withdraw enough each year to be in a tax bracket that’s even close to what we’re in now. There’s a reason people believe Millennials are facing a retirement crisis.

Moral of the story? It pays to know how much your life costs and what it’ll cost to support that life indefinitely.

More importantly, it pays to know how you’re (likely) going to earn, and make “Traditional vs. Roth” decisions accordingly. Let’s look at a few different scenarios:

-

Average earner who works for 25 years

-

Average earner who works for 40

-

High earner who works for 25

-

Person who goes from average to high earner within the first decade of their career, but keeps their lifestyle the same

An example with an average earner over 25 years

So let’s take our average earner: Someone making $60,000 per year.

We’ll say they start work at 22, earning $60,000, and receive a 4% raise every single year.

Let’s also pretend that their lifestyle costs $40,000 per year ($3,333 per month), and it goes up 3% per year for inflation.

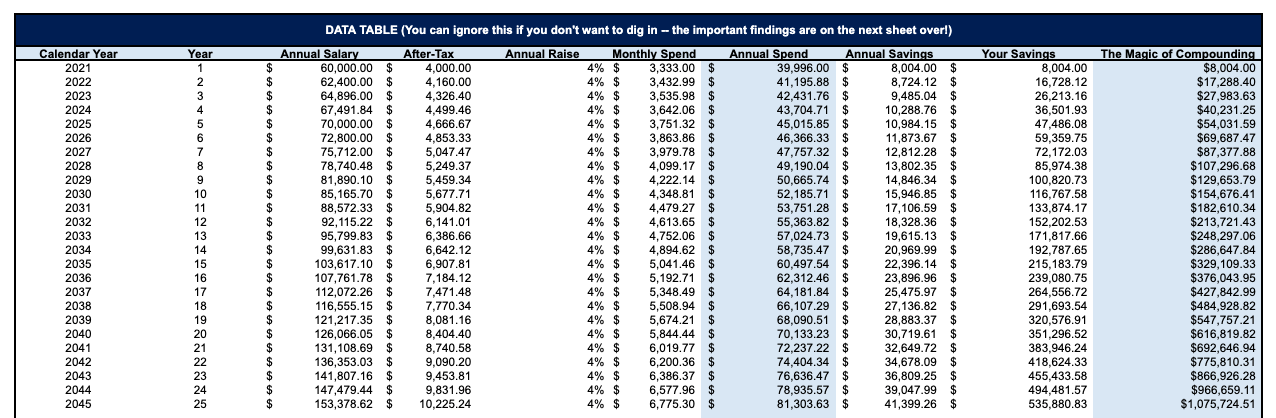

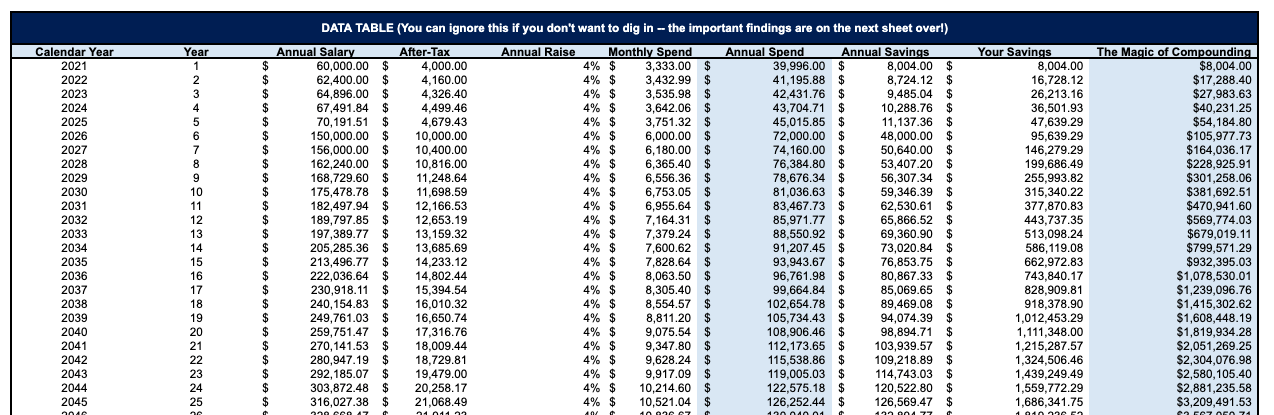

Here’s how much they’d accumulate over their working life (the far right column, in blue):

Notice how this individual (who increases their salary by 4% per year and increases their spending by 3% per year) ends up with approximately $1M in retirement after working for 25 years (age 22 > age 47). You can see how much they saved each year in the “Your Savings” column, as well as how much their investments turned into thanks to the magic of compounding.

The “Annual Savings” column shows how much this person saved each year – they’re nowhere close to contributing the maximum to a 401(k), especially in the first 14 years.

This individual probably hypothesized (at least, in the beginning of their career) that they’d definitely be in a higher tax bracket in retirement.

But remember how we’re taxed? We’re taxed based on how much we withdraw (read: spend), because we no longer have an income. Our withdrawals from our 401(k) become our income.

At $1,075,724, the safe withdrawal rate is $43,028 per year. That’s a problem, because you’ll note that – in 2045 – this person’s annual spend is $81,303 (thanks, inflation).

In reality, this individual would not be able to afford to retire yet, because they’d only be able to cover roughly 53% of their annual expenses (assuming no social security or other sources of income, like a pension).

That means that – at no point in this person’s career, even in year 1! – were they in a lower tax bracket than they would be in retirement, if they retired at this point (though, as we’ve noted, they wouldn’t yet be able to).

With a (relatively) short timeline of 25 years and an average income, it’s almost impossible – even if your final salary is $153,378.

So what happens if we extend that timeline to 40?

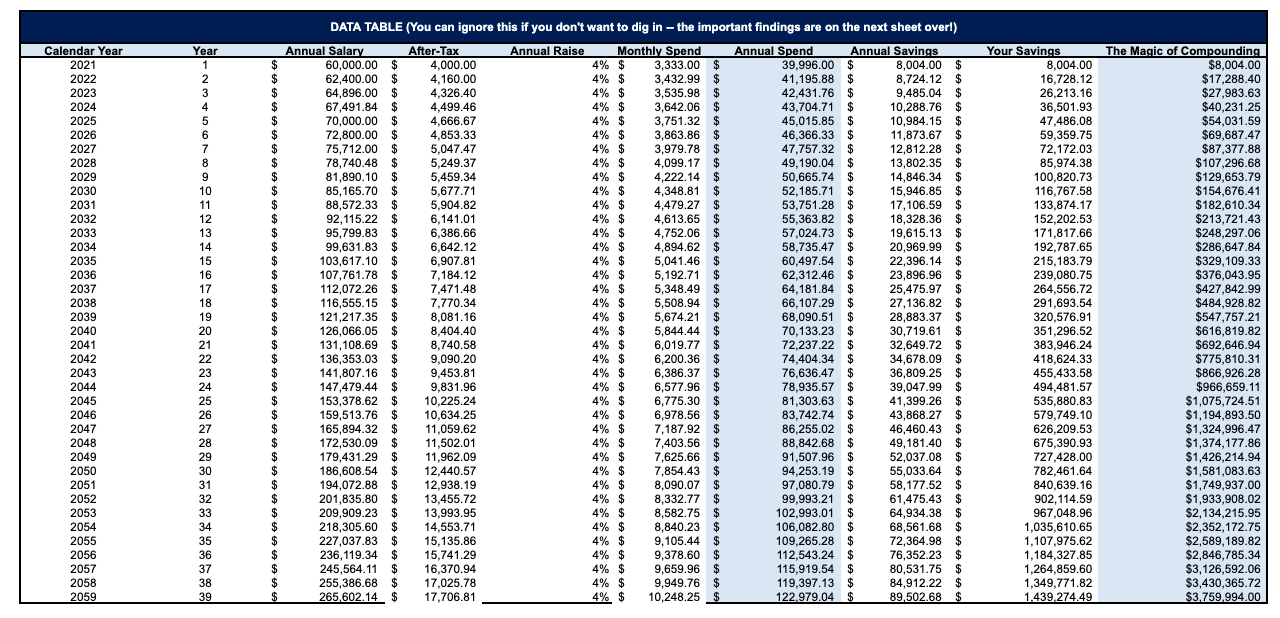

An example with an average earner over 40 years

Well, 39 – for some inexplicable reason, I set this spreadsheet to project 39 years into the future instead of 40. This is why I’ll never work for Goldman.

But here’s how things would change if the timeline extended through (almost) a full 40-year working life, with the individual retiring at 62.

This person – adding 15 more years to their working life – would retire with $3.7M in 39 years from now. Of course, our living expenses have to keep up with inflation, too, which means our “$40,000/year life” costs $122,979 in 2059. $3.7M’s safe withdrawal rate is $148,000, so this individual could cover their expenses and then some. They’re ready for retirement. Hell yeah, #RichGirl! But the tax brackets also shift upward, remember? They (usually) adjust upward each year with inflation – so it stands to reason that the government in 39 years will (more or less) tax a $122,000 withdrawal the way it taxes a $40,000 withdrawal today (again, because this is just $40,000 adjusted for 39 years of inflation – the purchasing power would theoretically be the same, though I want to acknowledge that it’s also totally possible we’ll all be Daddy Bezos’s Amazon robots eating dog food through a feeding tube by 2062, and this could all be moot). And again, we’re in the same boat. Sure, this individual may be withdrawing somewhere between $122,000 and $148,000 per year from their account, but the tax brackets will have had 39 years to shift upward with inflation – if the purchasing power of that money is still equivalent to somewhere between $40,000 and $60,000 today, this individual was still never in a lower tax bracket in their working life than they would be in retirement. Put another way : It’s almost impossible to invest enough money over your working life to be able to withdraw your way into a super high tax bracket in retirement without making a lot of money (and being in a high tax bracket) in your working life. Let’s look at the other side of this: A high earner who works for 25 years. Let’s say we have an individual who makes $150,000 per year but spends like our friend who makes $60,000 ($3,333 per month). The intent here is to show what would happen if someone who made a ton of money still lived modestly and invested the majority of their income. Their picture looks a lot different:

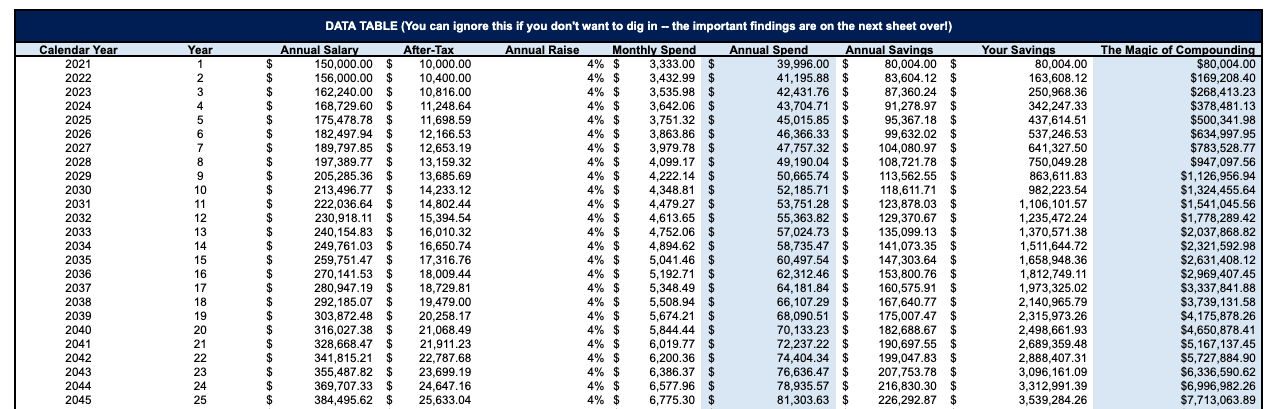

If this individual works for the same 25 years and only increases their spending by 3% per year in the same way, they’ll retire with $7.7M.

(Maybe the point of this article should be: Increase your income.)

The safe withdrawal rate on $7.7M? $308,000.

Now, the gap between this person’s annual expenses ($81,000) and the amount they can withdraw ($308,000) is quite wide. Moreover, $308,000 has (when adjusted for 25 years of inflation) the equivalent purchasing power of about $156,000 today.

You could argue that there are a few things about this scenario that may not stand up to the “practicality test” of how most people behave in the real world:

-

Most people making $150,000 don’t live on $40,000/year.

-

…and those who do are likely doing so because they intend to retire early, which means…

-

…they’re probably not going to work for a full 25 years. This individual would technically reach FI at $1.3M and be able to retire in year 10, after which point they could safely pull the ripcord well before accumulating $7.7M.

But let’s pretend they didn’t! Let’s stay true to our mathematical #roots here and pretend that we do have someone making $150,000, living on $40,000, and working for a full 25 years, finishing their career with a salary nearing $400,000.

You may look at this person and say, Well, shit, they can withdraw $300,000 per year! They didn’t make $300,000 per year until Year 19… Which means they were in a lower tax bracket for the first 19 years of their career, right?

Close, but I think the important thing is the inflation-adjusted value of that $300,000 per year withdrawal. Remember? It’s the equivalent of $156,000 today, which means it stands to reason that $308,000 in the future will be taxed the way $156,000 is taxed today (again, thanks to inflation).

And how long did it take them to be in a higher tax bracket than $156,000 per year? Year 2. It took them one year of work to eclipse the (seemingly insane) retirement tax bracket triggered by an outrageous $300,000/year drawdown, made possible by the fact that they made $150,000/year and lived on $40,000.

Even a high earner who lives on very little, works for 25 years, and amasses $7.7M of wealth would have a hard time getting into a higher tax bracket in retirement

Someone whose lifestyle is conducive to spending more than they earn is not going to amass the type of wealth necessary to spend that much in retirement. There’s really only one instance that I can think of where someone would potentially find themselves in a “higher tax bracket in retirement” scenario, and it’s a perfect segue to our third and final piece of pushback: You’re in a really low tax bracket right now (10% or 12%) but believe you’ll be in a much higher one for the majority of your career.

That is to say:

People who start with a low or average salary, but become high earners relatively quickly – and don’t inflate their lifestyles to match – may be in a lower tax bracket in the very beginning of their careers before their salaries balloon.

Going from an average income to a high income isn’t enough – because remember, the amount we can spend in retirement is based fully and completely on (a) how much we saved and (b) for how long.

If you spend 90% of your income on $60,000/year and also spend 90% of your income on $150,000/year, you’re no better off.

Let’s take a look at this scenario.

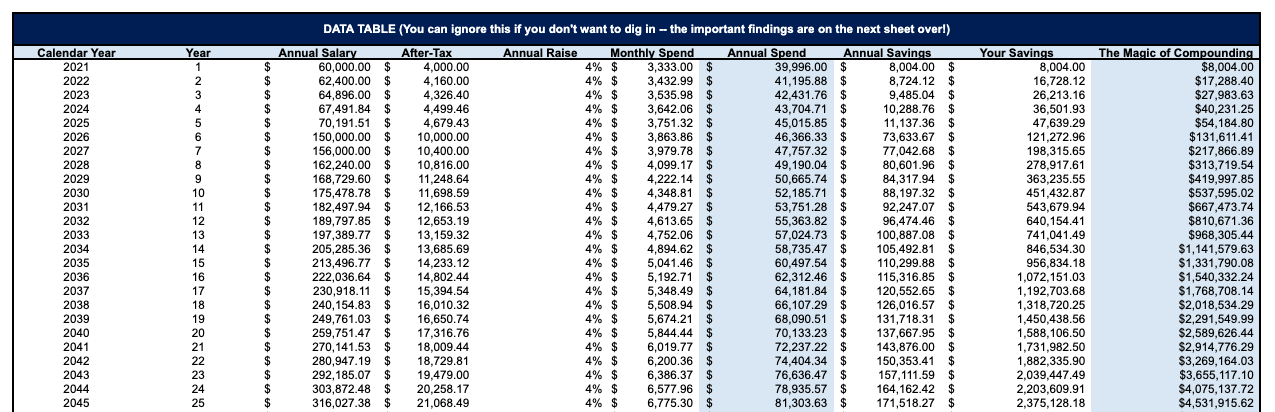

An example with an average-to-high earner for 25 years (who doesn’t inflate their lifestyle)

Let’s assume this person is an average earner for the first 5 years of their career and then takes a rocketship to the 24%+ marginal tax bracket.

In this instance, where someone doubles their income in year 5 but sustains their same lifestyle indefinitely, they skid into year 25 with $4.5M – giving them a safe withdrawal rate of $180,000 (much higher than the $81,000 they need). That’s equivalent to about $75,000 of purchasing power in today’s dollars, which means that (using our same logic) – if they were to withdraw $180,000 in their first year of retirement, they’d theoretically be in a higher tax bracket than they were in their first 5 years of working.

If you believe that your early salary is going to double or triple relatively early in your career (which can happen!) but you plan to continue to live a similar lifestyle, the math would indicate there’s a good chance you’ll be in a higher tax bracket in retirement.

But if you inflate your lifestyle? Say, you start spending $6,000/mo. instead of $3,333 when you get your big fat raise? Let’s see:

Now, you hit year 25 with $3.2M, not $4.5M – and you need $126,252 (not $81,303) to support your lifestyle. Lucky for you, the safe withdrawal rate on $3.2M is $128,000, which means you’ve got just enough to cover your expenses. But remember – $128,000 in 25 years from now is the equivalent of about $70,000 today, and by year 5, they were already in that “$70,000” bracket.

Contributing the maximum to a 401(k) every year for 25 years likely won’t be enough to retire if that’s all you’re doing

That is, unless your needs are very conservative.

It’s more or less mathematically impossible for someone to find themselves in a position where their 401(k) is “too big” if it’s the only account they plan to live on, because they won’t be able to safely withdraw the entire amount they need from it without depleting it too quickly. This makes the concern around “being in a higher tax bracket in retirement” very unlikely, barring an environment where there are sustained high returns and abnormally low inflation for decades (which, like… that would be a GREAT ‘problem’ for all of us!).

The 401(k) alone will not be enough – you’ll need income from other sources, like Roth IRAs or taxable accounts.

And that, my friends, is where the zesty, terrifying rubber meets the road.

Because you can claim up to $96,700 of long-term capital gains in 2025 (for married filing jointly) in today’s dollars at a whopping 0% tax rate, you can structure your drawdown from your various accounts such that you’re converting smaller chunks from your 401(k) each year. That’s why I feel so passionately about tax-deferred accounts and delaying Roth conversions until you’re in total control of how that tax gets paid – because while I hear the Roth arguments in theory, in reality, it’s relatively easy to limit (or completely eliminate) your tax liability later in life when your earned income is zero (or close to zero).

All right, time to dissipate the painful, bleak dark cloud I’ve just ushered in – that won’t be you, right? Because you’ve got time and Money with Katie on your side (but in all seriousness, make sure you adjust for inflation).

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time