Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

Let me ask you a question: Do you consider yourself wealthy?

Whether you do or you don’t, what’s your justification for your answer?

If I had to guess, it has something to do with comparison to people in a similar situation to you, as opposed to any hard-and-fast numbers: If you look around at your life, income, and net worth, and that of people similar in age and geography, do you feel like you’re better off, or worse?

This question is fascinating to me—more accurately, the answers are fascinating.

It’s funny how you might hear someone who makes $60,000 per year and drives a leased Mercedes describe themselves as wealthy, while someone with hundreds of millions of dollars may not.

In a lot of ways, it’s not always subjective. This MarketWatch article from 2018 points out (depressingly) that a staggering number of Millennials (65%) believe they’ll be “rich” in the not-too-distant future. That’s adorable ‘n optimistic, but when you look at the saving behavior of many Millennials, it wouldn’t suggest that’s a realistic assumption (roughly the same number of Millennials have nothing saved for retirement).

Some call it the Mark Zuckerberg effect, presumably implying that our generation has a few shining tech stars that make us believe unthinkable fortune is on the other side of just one good idea that starts as a means for comparing girls’ respective levels of hotness but eventually morphs into a society-altering, democracy-damaging invention. #oopsie

I’d agree with the Mark Zuckerberg effect—but with a totally different definition.

My oversimplified theory? The apps that Mark owns drive this warped belief system that everyone’s richer than they actually are.

Why? Because these apps commodify, memorialize, and aggregate the natural comparison that plagues every generation of human beings. “The Joneses” are no longer just the people who live in the McMansion next door to you and drive a newer Buick than you do—the metaphoric Joneses are now any one of the 1 billion people you can follow on Instagram.

Pre-social media, you didn’t know that there were a slew of cool teens parading around Los Angeles in G Wagons and Gucci sweaters drawing from an inexplicable and invisible pool of funds despite having no discernible job beyond being hot and intriguing on the internet.

This is not a new or novel idea (in fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve written about it before), but I was thinking about it in a more in-depth way the other day after receiving a DM that went something like this:

“Do you think people who make a lot of money still don’t feel wealthy because our idea of what constitutes a good life that we deserve to be living in America is just warped to shit?”

(Expletives mine.)

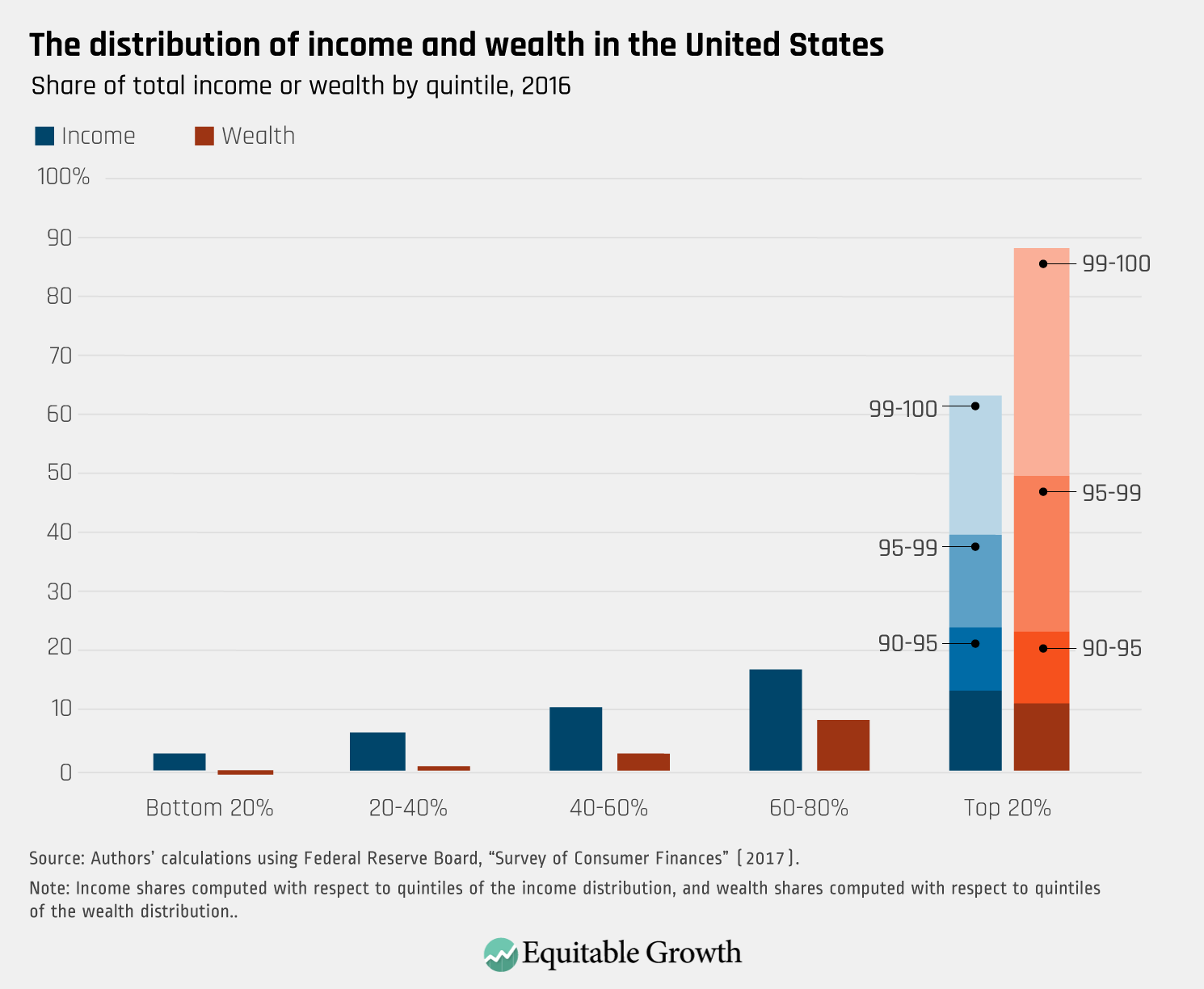

It’s an interesting phenomenon. In America, we see opulent displays of wealth portrayed as relatively normal. The top 1% of richest people in America control 16x as much wealth as the bottom 50%. Yeah. No matter how bad you think the wealth inequality is, I can almost guarantee you: It’s worse than that.

Think about reality television for a second: The name itself implies it’s reflective of reality.

But whose reality?

Shows like Real Housewives, Keeping Up with The Kardashians and its 17 spinoffs, Below Deck, Selling Sunset and Vanderpump Rules are among some of the most popular that don’t revolve around one person dating 25 people at once in a New Mexico mansion.

It doesn’t take an Ivy League degree to recognize that all of these “reality” shows depict the lives of 1%-level wealth (or those defrauding their way to it). Kylie Jenner, the 24-year-old KarJenner with more money than any of the rest of ‘em besides Ole’ Kimmy, is reported to be worth about $700 million. She has handbags that cost more than the median home in the United States. Scenes of the show depict her standing in her 1,600-square foot closet surrounded by millions of dollars worth of handbags and shoes, having a casual conversation about what to eat for dinner: The juxtaposition fuels an almost-comedic level of absurdity.

I can’t remember (or find) the name of the social psychology phenomenon, but it’s a little bit like why people think plane crashes and gun violence are more prevalent than they actually are: When you’re super exposed to something (via news or popular culture), it feels more commonplace than it actually is. You think something is more likely to happen to you than it actually is, statistically speaking, because you hear about it a lot.

It’s easy to feel like you’re falling way behind—or deserve a lot more than—what’s reasonable.

So let’s explore: How wealthy are you?

To answer this question, we first must zoom out and get a healthy dose of #perspective.

Let’s expand our horizons for a moment to consider the entire world.

According to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report from 2021 (which you can download and peruse here), you’re in the top 1% of wealth globally if you have more than $1 million.

If you have between $100,000 and $1 million, you’re in the top 10% of richest people in the world.

Between $10,000 and $100,000? You’re still in the richer half.

39% of all global millionaires live in the United States. To contextualize how wild that is, consider that the next-largest chunk comes from China, clocking in at just 9%.

That may make it seem like you’ve got a better shot at becoming a millionaire in the US than in the rest of the world, but it’s important to remember the scale here: Only 8.8% of Americans are millionaires, whereas 15% of the Swiss population holds this title. Still, America’s “percentage of population considered millionaires” still ranks 3rd globally, surpassed only by Switzerland and Australia.

And the percentage of Americans with Kardashian-level wealth is even smaller: Roughly 80,000 Americans (0.02%) have between $50 million and $100 million. Last time I checked, the Kardashians account for 6 of the 80,000, not including their spouses. Well-played, Kris Jenner. (I suppose a few of them don’t even fall in this group, as Kim is worth a billion, Kylie’s got $700 million, and Kris is worth more than $100 million. They’re part of an even smaller upper echelon.)

Cool. So that’s that. These numbers tend to vary depending on the source (which makes sense, given they’re likely a little hard to track definitively), but the ballpark is telling.

Let’s zoom in now to the US alone and think about income alone for a moment.

How rich is rich in the US?

To be a top 0.1% earner in the US, you have to earn a staggering $3.2 million per year.

To be a top 1% earner, $823,763.

Top 5%? $342,987.

Top 10%? $173,136.

If you’re placing yourself in the above brackets, congratulations: You’re part of the chunk of the United States that’s doing very well. Some of you may remember when I shared this depressing wealth inequality chart a few months ago:

So what about a top 1% minimum net worth in America? The EPI placed that number around $11.1 million in 2021.

Age plays a role, too: “If you’re younger than 35 and you have a million dollars, then yes, you are rich. You are above the cutoff for the 99th percentile of household wealth for that age, which is $998,000.”

So what’s the point of all this? Well, for one thing, to put things in perspective a little bit. Even if you don’t feel rich, if you have more than $100,000, you’re richer than 90% of the world population.

Some people may feel annoyed by this: Who cares if I’m “richer” than the rest of the world if I can’t make ends meet?

This was the crux of the original DM that spurred the comment about a warped sense of reality: Someone had DM’d to say they felt stretched thin as a single mom making $200,000 per year.

Some people were outraged by this, and I suppose understandably so: $200,000 per year is no small sum.

It got me diving into all of the above, as well as another related question: Why does life in America cost so much?

At the risk of clobbering the dead horse, I think it can be traced back to two major things: a lack of social safety nets (everything from healthcare to education to childcare to elder care is considered an individual responsibility with premium costs associated) and the wealth inequality we saw above.

What about median measures of wealth and median costs in the US?

Now that we’ve taken a stroll down Rodeo Drive and feel sufficiently broke as fuck, let’s flip the script:

We’ve seen what it takes to be the richest of the rich in America and experience the opulent lives of those on E! and Bravo…but what about the median income and net worth in America?

To be clear, the “median” can be a better metric for measuring what life for most is like, as opposed to an “average” that can be skewed by extreme outliers.

The median tells us—if we lined up each and every of the 332 million people that live in the United States from richest to poorest—what the 166 millionth person would make. The person in the dead middle of the line.

The median household income in the US (let’s assume two adults) is $74,099, according to data that came from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The median net worth in the US was $121,700 in 2019 (page 11).

That means roughly half the country has less than $121,700, and the other half has more.

A median income of $74,099 doesn’t sound too bad—until you consider that the inflation-adjusted median income in 2000 was $67,428. That’s a real growth of $6,671 over 22 years, or the equivalent of a “real” raise of $303 per year.

Meanwhile, the median home value in 2000 was $219,232 adjusted for inflation (meaning that’s the “2022 dollars” version of the price; the nominal price at the time was closer to $98,000).

The median home value today is $355,876.

That’s a real increase of $6,211 per year. It’s not hard to see why a $303 raise in median income won’t cut it.

It’s a little bit like what Barry Ritholtz wrote: “The costs of what we need keep rising, while the cost of the junk we want keeps falling.”

To summarize neatly: If you feel like your life costs more and more and you’re not able to live as well as your parents were on the same (or less), you’re not imagining things. Things are getting more expensive, and real wage growth is slowing (unless, of course, you’re in that coveted top 1%—then you would’ve seen a real wage growth of 179% since 1979, as opposed to the 28% real growth experienced during the same period by the bottom 90% of earners).

One of the articles I was reading put it well: “If you’ve got $2 million, you’re probably rich. $1 million isn’t really what it used to be.”

I’m not trying to come to any moral conclusions about this state of affairs: I’ll let you come to your own conclusions about whether or not this is the direction we want to go.

But what I do want is to level-set for #RichGirl nation and serve all of us (me included) a reality check.

Shit’s getting harder for the middle class. Hell, if we’re to believe the 60% of Millennial six-figure earners living paycheck to paycheck, it’s not just getting harder for the middle class. (Ironically, six-figure incomes are now considered lower-middle class in some parts of the country.)

And that’s not really the point: The point, dear Rich Girl, is this:

Building wealth is now both harder and easier than it’s ever been

Harder in the sense that the costs of your basic living expenses (the “stuff you need”) are rising faster than wages. Harder in the sense that we’re more exposed than we’ve ever been to the lifestyles of the ultra rich, through both reality television and social media. The temptation is greater than it’s ever been for us to compare our seemingly average-ass lives to others.

But it’s easier in the sense that the barrier to entry to invest has really never been lower. Do you have an internet connection and $5? You can invest in a matter of minutes for free. Literally.

Understanding that your own perception of the type of life you “deserve to” or “should” be living is likely distorted can be the magic formula here: It helps you stay grounded in your expenses and instills an appropriate amount of scarcity mindset.

Paradoxically, in this way, you’re probably both better off and worse off than you believe. If you feel broke as hell making $80,000 per year, you can remind yourself that you’re still richer than most of the world’s population—while simultaneously recognizing that $80,000 isn’t enough to live like a king in the United States.

I caught myself in this same trap the other day: I make a “top 5%” income in America, and I found myself staring longingly at Kylie Jenner’s forearm full of Cartier LOVE bracelets. Each one ranges in price from $5,000/pop to well over $10,000, depending on how many diamonds it’s encrusted with.

“What if I got a Cartier LOVE bracelet?” I began to wonder, meandering through the website and sorting the bracelets by “Price: Low to High.” (Note to self: Sorting jewelry by “Price: Low to High” is probably a good sign you shouldn’t be buying it. The most hilarious and extreme epitome of “I deserve a treat,” culture.)

I was admiring one with a price tag north of $5,000 when I had a rude awakening and snapped out of it: $5,000 for a bracelet represents less than 0.0007% of Kylie’s total wealth.

$5,000 represents about .8% of mine. Almost a full percentage point.

Kylie spending $5,000 on a bracelet would be the equivalent of me buying something that costs $4.

I didn’t get the bracelet.

So how rich are YOU?

There’s a metric offered in the book The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas J. Stanley that helps you calculate whether or not you’re accumulating wealth at the appropriate rate based on how much you earn, which isn’t exactly the same thing as determining whether or not you’re rich, but purports to be a good measure of whether or not you’re on the right track.

Take your total annual pre-tax income x your age ÷ 10.

That’s what your net worth “should” be.

When I did this exercise, it told me that I should have $1,080,000.

On my own, I have roughly half that. My household has about that much.

I’d consider myself a pretty damn good saver, and I’m (clearly) nowhere close.

How do you stack up?

April 25, 2022

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time