Continue Reading

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

Join 200,000 other people interested in money, power, culture, and class.

Subscribe

Last December, I took three of my best friends on a trip to Tulum, Mexico. It was the first time I had ever done something so grand, and a few days ago, I woke up thinking again of Tulum. I navigated to our choice hotel’s site to check booking availability, making a mental note of the approximate dates and prices for a five-day trip. I was already drafting the invitation text in my head and giddy at the prospect of returning.

Later that day on our back patio, I was looking out at the small lake our house backs up to. When it’s time to buy a house, I’ll want to buy on the water, I thought dreamily, plodding down the well-worn path of mental Zillow window shopping, envisioning a home I would desire enough to drain my savings for. (Forget this lake I already live on, right?!) My fantasy involved a midcentury modern affair—heavy on the trees and windows, and light on the “suburbia”—located near friends and family in Boulder, Colorado.

Before long, mental Zillow turned into actual Zillow. I scrolled through listings on Mid Mod Dream Homes to get a better sense for how much the dream bungalow would set me back. How much could it be?

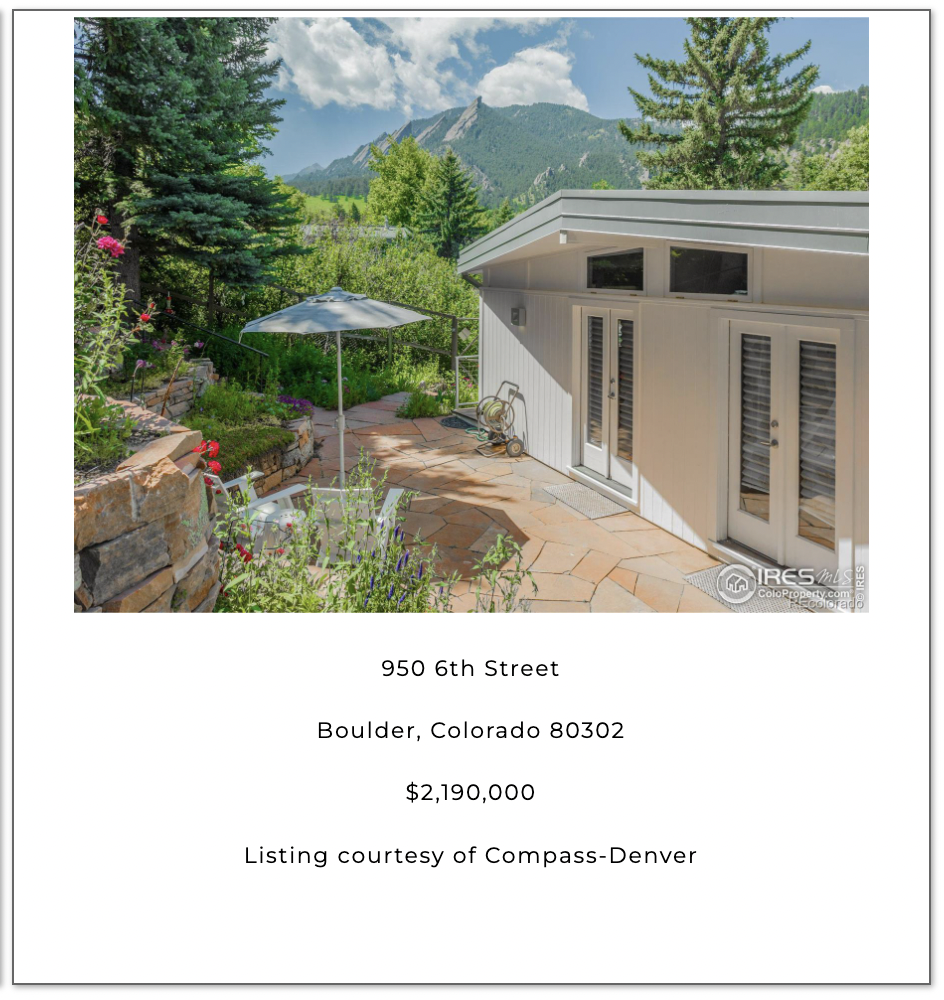

There were no lakes in sight, but my eyes settled on a Boulder property with the mountains in the background, selling for $2,190,000.

Oh.

That’s…divide by two, carry the one…a $438,000 down payment and a cool $15,000 monthly payment toward PITI with a 7.55% interest rate.

Insert GIF of balloon slowly deflating. “Well, that’s not going to happen,” I said aloud, to no one.

My eyes flickered to the tab from just a few hours prior, when I was thrilled at the prospect of treating myself and my friends to another week at the beach—a vision that now felt wanton in light of the knowledge that an 1,800 s.f. home in Boulder was going for $1,200 per square foot.

I can’t make a habit of vacationing with friends if I’m ever going to buy my dream house on the Front Range, I scolded myself, scanning my life for other pleasurable-but-expensive nonessentials I could cut for the next decade to become the type of person who was worthy of purchasing a $2m, three-bedroom home.

This guilt—coupled with the fact that I knew I would probably never purchase such a gilded palace—left me feeling stuck between a rock and a hard place (and decidedly not of the Rocky Mountain variety).

>

“There’s something a little backward about the implicit suggestion in the US that people should orient their entire lives around purchasing the structure they live in, particularly now, when housing affordability is at an all-time low. ”

The deflation was less about this specific home, and more about what “eventual home ownership” represented in that moment: the thing for which all else must be necessarily deprioritized.

These are, of course, incredibly privileged problems. But as someone who writes about money on the internet, I talk to young people all the time who are delaying, downsizing, or altogether abandoning other interests in pursuit of one, singular dream: owning their dream home. They’re ambitious, double-income couples working 50+ hours a week and dutifully saving thousands of dollars a month in service of this objective.

Normally, this is the type of arrangement we smile upon in the personal finance world. Good little millennials, we think, successfully navigating the temptations of modern life and socking away tens of thousands of dollars per year to save up for that six-figure down payment.

And to some extent, it is wonderful: Working toward a goal makes us happy. It makes us feel good about ourselves, particularly when it aligns with the “right” type of ambition. A financial goal of “taking a vacation with your friends every year” isn’t likely to garner the same approving head nods.

Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling that there’s something a little backward about the implicit suggestion in the US that people should orient their entire lives around purchasing the structure they live in, particularly now, when housing affordability is at an all-time low.

If an alien came to earth and witnessed these individuals sacrificing and stockpiling all of their discretionary resources—for years and years—in pursuit of a down payment, I could imagine them saying, “But wait, you already have a structure to live in?”

“Yes,” the couple would reply, eyes twitching, too drunk on the Redfin haze to be startled by the extraterrestrial in their rented living room, “But someone else owns this one. Unacceptable!”

>

“A lifetime of renting connotes something adjacent to ‘failure’ in the US.”

The home this prototypical couple likely has in mind—and the home worth a decade of sacrifice—is not your $416,000 “median” home. At that point, they figure, you might as well extend a lease. Why struggle to afford something that isn’t even as nice as the spot you’re currently renting with relative ease? If you’re going to do all the work to step up to the financial plate of home ownership, you might as well swing for the fences, they think.

Given how challenging it is to buy any home today, the home worth striving for has to seem good enough to inspire a commensurate level of sacrifice. Enter: the dream home.

For many, it’s not a vision pursued out of joy or a generative vision of the future, but out of fear of the alternative: A lifetime of renting connotes something adjacent to “failure” in the US.

But could the things we’re trying to achieve through home ownership largely be achieved through better protections for renters? Is it worthwhile to revisit the “ownership society” paradigm that local and federal governments have spent (at least) the last 50 years creating? Who does it really work for anymore? Who has it ever really worked for?

After all, it’s not like buying a home has ever been “easy,” just varying degrees of really hard: I also speak frequently with older people about their financial lives—people in their forties, fifties, and sixties—who regale me with tales of struggling for years to buy their home. Working late, working weekends, skipping vacations, skipping meals. “But we did it!” they exclaim, “and it was worth it.”

Consider the fact that roughly one in two millennial homeowners under the age of 34 needed financial support from someone else in order to buy their home. This is a trend that I’m beginning to think has always been the norm—it’s a footnote I notice in most stories from my Gen X and Baby Boomer pals, too, mentioning how someone’s dad had to gift or loan the down payment.

>

“Maybe the best solution is renting until you’re able to buy the most reasonable home you can comfortably afford, and leaving the ‘dream home’ thing to HGTV.”

When millennial couples used to tell me they were making painstaking sacrifices to get into a home, I used to applaud them for their commitment to financial prudence. Now, I can’t help but wonder if they’ve been sold on what’s ultimately a pretty raw deal. Would having my name on a deed for a midcentury modern home—rather than on a lease for one—really make me happy enough* to forgo the next 10 years of girls’ trips (and more!) it would require? I’m not so sure.

Still, the alternative in the current paradigm—where rents can be raised in most states with basically no legal limitation—leaves a lot to be desired, too. Maybe the best solution is renting until you’re able to buy the most reasonable home you can comfortably afford (yes, even if it takes much longer), and leaving the “dream home” thing to HGTV.

*Data from PWL Capital suggests the opposite might be true: “Empirically, homeowners are not happier, and may be less happy, than renters after controlling for income, housing quality, and health. Owners also spend less time on enjoyable activities like active leisure and more time working on their homes.”

October 16, 2023

Paragraph

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time